If only the world had no boundaries and we could move about without having to produce passports and documents everywhere, it really would be a great wide beautiful, wonderful world’, says Ruskin Bond.

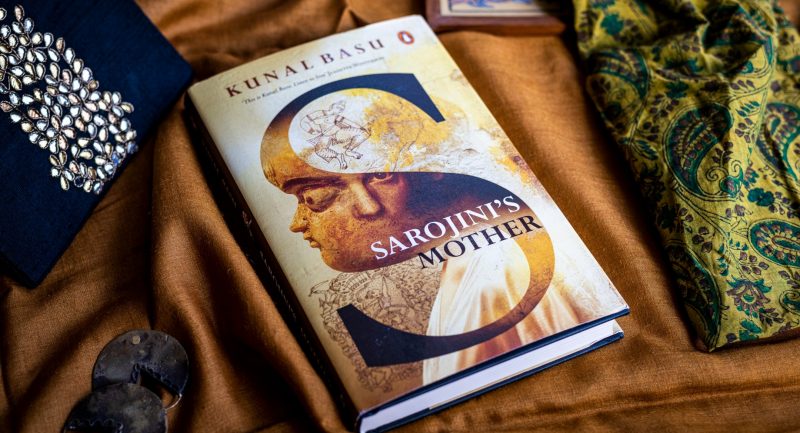

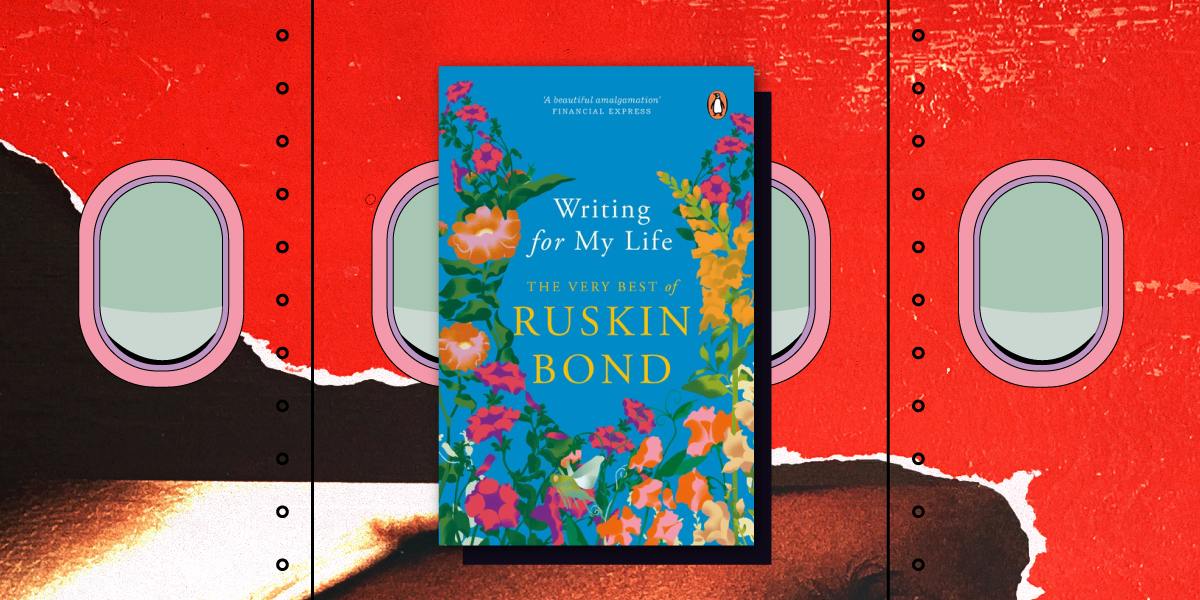

From his most loved stories to poems, memoirs, and essays, Writing for My Life opens a window to the myriad worlds of Ruskin Bond, India’s most loved author. This book is full of beauty and joy – two things Ruskin’s writing is mostly known for.

Ruskin’s writing is greatly inspired by the places he lived at. His first book The Room on the Roof was published when he went away to London but was inspired by Dehradun. Here are some excerpts from stories based out of Dehradun, Jersey, and London

Dehradun: The Window

I came in the spring and took the room on the roof. It was a long, low building that housed several families; the roof was flat, except for my room and a chimney. I don’t know whose room owned the chimney, but my room owned the roof. And from the window of my room, I owned the world.

But only from the window.

The banyan tree, just opposite, was mine, and its inhabitants my subjects. They were two squirrels, a few mina, a crow, and at night, a pair of flying foxes. The squirrels were busy in the afternoons, the birds in the mornings and evenings, the foxes at night. I wasn’t very busy that year; not as busy as the inhabitants of the banyan tree.

There was also a mango tree but that came later, in the summer, when I met Koki and the mangoes were ripe.

At first, I was lonely in my room. But then I discovered the power of my window. I looked out on the banyan tree, on the garden, on the broad path that ran beside the building, and out over the roofs of other houses, over roads and fields, as far as the horizon. The path was not a very busy one but it held variety: an ayah, with a baby in a pram; the postman, an event in himself; the fruit seller, the toy seller, calling their wares in high-pitched familiar cries; the rent collector; a posse of cyclists; a long chain of schoolgirls; a lame beggar…all passed my way, the way of my window…

*

Jersey – A Far Cry from India

It was while I was living in Jersey, in the Channel Islands, that I really missed India.

Jersey was a very pretty island, with wide sandy bays and rocky inlets, but it was worlds away from the land in which I had grown up. You did not see an Indian or eastern face

anywhere. It was not really an English place, either, except in parts of the capital, St Helier, where some of the business houses, hotels, and law firms were British-owned. The majority of the population – farmers, fishermen, councillors – spoke a French patois which even a Frenchman would have disowned. The island, originally French, and then for a century British, had been briefly occupied by the Germans. Now it was British again, although it had its own legislative council and made its own laws. It exported tomatoes, shrimp, and Jersey cows, and imported people looking for a tax haven.

During the summer months, the island was flooded with English holidaymakers. During the long, cold winter, gale-force winds swept across the Channel and the island’s waterfront had a forlorn look. I knew I did not belong there and I disliked the place intensely. Within days of my arrival, I was longing for the languid, easy-going, mango-scented air of small-town India: the gul mohur trees in their fiery summer splendor; barefoot boys riding buffaloes and chewing on sticks of sugarcane; a hoopoe on the grass, bluejays performing aerial acrobatics; a girl’s pink dupatta flying in the breeze; the scent of wet earth after the first rain; and most of all my Dehra friends.

So what on earth was I doing on an island, twelve by five miles in size, in the cold seas off Europe? Islands always sound as though they are romantic places, but take my advice, don’t live on one – you’ll feel deeply frustrated after a week.

I was in Jersey because my Aunt E (my mother’s eldest sister) had, along with her husband and three sons, settled there a couple of years previously. So had a few other financially stable Anglo-Indian families, former residents of Poona or Bangalore, but it not a place where young people could make a career, excerpt perhaps in local government.

I had finished school at the end of 1950, and then for almost a year I had been loafing around Dehra Dun, convinced that I was a writer on the strength of a couple of stories sold to The Hindu’s Sport and Pastime (now there was a sports’ magazine with a difference – it published my fiction!) and The Tribune of Ambala (Chandigarh did not exist then). My mother and stepfather finally decided to pack me off to the U.K., where, it was hoped, I would make my fortune or become Lord Mayor of London like Dick Whittington. There really wasn’t much else I could have done at the time, except take a teacher’s training and spend the rest of my life teaching As You Like It or Far from the Madding Crowd to schoolboys (in private schools) who would always have more money than I could earn.

Anyway, my aunt had written to say that I could stay with her in Jersey until I found my bearings, and so off I went, in my trunk a new tweet coat and two pairs of grey flannel trousers; also a packet of haldi powder, which my aunt had particularly requested. During the voyage, the packet burst, and most of my clothes were stained with haldi.

*

London – And Another in London

Although for my first six months in London I did live in a garret and an unhealthy one at that, I did not really see myself in the role of the starving poet. The first thing I did was to

look for a job, and I took the first that was offered – the office job at Photax, a small firm selling photographic components and accessories. A little way down the road was the Scala Theatre, and as soon as I had save enough for a theatre ticket (theatre-going wasn’t expensive in those days), I went to see the annual Christmas production of Peter Pan, which I’d read as a play when I was going through the works of Barrie in my school library. This production had Margaret Lockwood as Peter. She had been Britain’s most popular film star in the forties and she was still pretty and vivacious. I think Captain Hook was played by Donald Wolfit, better known for his portrayal of Svengali.

My colleagues in Photax, though not in the least literary, were a friendly lot. There was my fellow clerk, Ken, shared his marmite sandwiches with me. There was Maisie of the auburn hair, who was constantly being rung up by her boyfriends. And there was Clarence, who was slightly effeminate and known to frequent the gay bars in Soho. (Except that the term ‘gay’ hadn’t been invented yet.) And there was our head clerk, Mr. Smedly, who’d been in the Navy during the War, and was a musical-theatre buff. We would often discuss the latest musicals – Guys and Dolls, South Pacific, Paint Your Wagon, Pal Joey – big musicals which used to run for months, even years.

The window opposite my desk looked out on a huge cinema hoarding, and it was always an event when a new poster went up on it. Weeks before the film was released, there was a poster of Judy Garland in her comeback film, A Star is Born, and I can still remember the publicity headline: ‘Judy, the world is waiting for your sunshine!’ And, of course, there was Marilyn Monroe in Niagara, with Marilyn looking much bigger than the waterfall, and that fine actor, Joseph Cotton, nowhere in sight.

My heart, though, was not in the Photax office. I had no ambitions to become a head clerk or even to learn the intricacies of the business. It was a nine-to-five job, giving me just enough money to live on (six pounds a week, in fact), while I scribbled away of an evening, working on my second (or was it third?) draft of my novel. The title was the only thing about it that did not change. It was The Room on the Roof from the beginning.

How I worked at that book! I was always being asked to put things in or take things out. At first, the publishers suggested that it needed ‘filling out’. When I filled it out, I was told that it was now a little too descriptive and would I prune it a bit? And what started out as a journal and then became a first-person narrative finally ended up in the third person. But editors only made suggestions; they did not tamper with your language or style. And the ‘feel’ of the story – my love for India and my friends in particular – was ever-present, running through it like a vein of gold.

Much of the publishers’ uncertain and contradictory suggestions stemmed from the fact that they relied heavily on their readers’ recommendations. A ‘reader’ was a well-known writer or critic who was asked (and paid) to give his opinion on a book. The Room on the Roof was sent to the celebrated literary critic, Walter Allen, who said I was a ‘born writer’ and likened me to Sterne, but also said I should wait a little longer before attempting a novel. Another reader, Laurie Lee (the author of Cider with Rosie), said he had enjoyed the story but that it would be a gamble to publish it.

Fortunately, Andre Deutsch was the sort of publisher who was ready to take a risk with a new, young author; so instead of rejecting the book, he bought an option on it, which meant that he could sit on it for a couple of years until he had made up his mind!

Experience the very best of Ruskin Bond’s writing in one book, Writing for my Life!