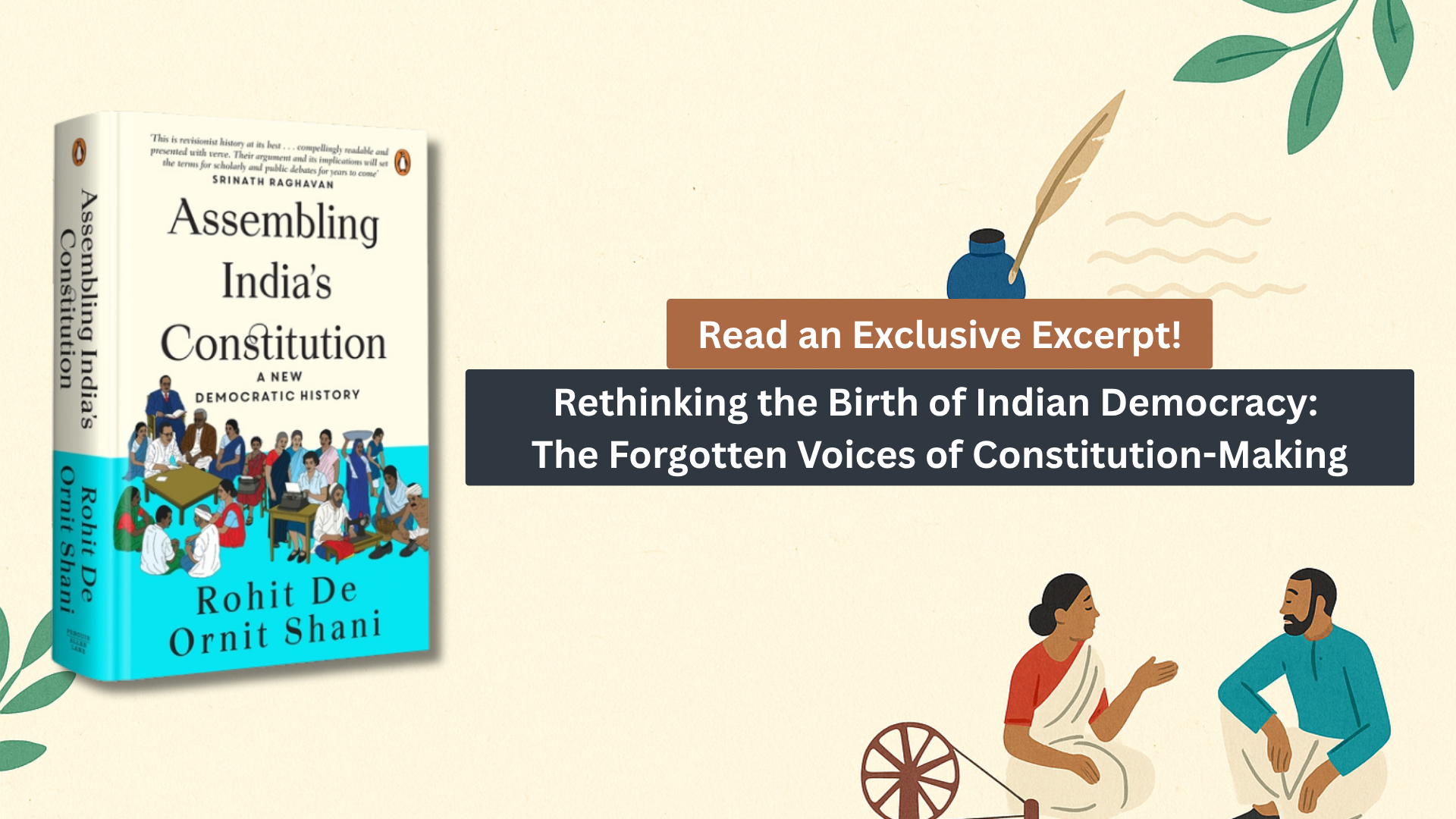

Read an exclusive excerpt from Assembling India’s Constitution: A New Democratic History by Ornit Shani and Rohit De — a groundbreaking book that reimagines how India’s Constitution came to be.

Introduction A New History of India’s Constitution Making ‘Everything was in a fluid state’, wrote the leaders of the Moshalchi community from Char Balasia village in an anxious letter that reached the Constituent Assembly of India in Delhi in May 1947. Life in their village, located at a tip of a char land at a fork of the Padma River in Bengal was precarious at all times. The char land was constantly subjected to the river’s mighty flow, and large pieces of land were cut off from one bank of the river to the other. Yet, in the early days of May 1947, the ‘fluid state’ at issue concerned imminent changes to their land brought about by political-administrative action rather than the force of nature. The eighty Moshalchi, who wrote on behalf of over 2,000 families, shared their concerns with the president of the Constituent Assembly of India:

The country is now on the threshold of momentous constitutional change. We did not press for justice so long as everything was in a fluid state. But now it is high time that the authorities should take stock of the situation and mete out even-handed justice. In the future constitution we should be treated as a separate Community, and there must be provisions for separate representation for us in the legislatures . . . so that our own culture and tradition may be maintained.

On the date that they drafted their letter, just two weeks before the announcement of the partition of India and Pakistan, the Moshalchi literally stood on shifting sand. Historically, as the river changed currents, it moved the char land across district boundaries and jurisdictions. They were, therefore, fully aware of the possibility that an international border could be drawn over their community. The Moshalchi professed Islam, but their letter reminded the Constituent Assembly that they were not fully recognised by the Muslim community and that they were ‘treated as out-caste, belonging neither to the Muslim nor to any other community’. Therefore, they explained, they were ‘crippled both politically as well as economically’.

At this critical moment, at the edges of freedom and political imagination, the Moshalchi saw an opportunity to achieve stability: to have their identity recognised, and their rights formalised in the new nation’s constitution. The Moshalchi were just one of countless groups and individuals across India who took such action and turned to the constitution as a resource for their future.

The story of India’s constitution making, as usually told, begins in the great metropolises of either London or Delhi. As the clock struck eleven on 9 December 1946, the story goes, the Constituent Assembly convened for the first time in Constitution Hall, New Delhi, to begin the prodigious task of framing a constitution for the soon-to-be-independent India, basing its work on a plan set by the British Cabinet Mission. The library hall of the Central Imperial Assembly was converted into the hall for the Constituent Assembly. The 205 assembly members who met on that morning, among them ten women, gathered in what was described as ‘an atmosphere charged on the one hand, with enthusiasm, and on the other with uncertainty’.5 In this classic account, a few key members of this group would become the founders of India’s constitution. In this telling, India’s good fortune was in having a handful of great men and women who, with foresight and benevolence, gifted a constitution to a people.

The Constituent Assembly’s members were not directly elected. They were, in the main, representatives of the elite, chosen by the legislative assemblies of the provinces of British India, which were themselves elected in the 1946 elections on the basis of a very limited franchise, and an electorate that was structured along religious, community, and professional lines, according to the colonial 1935 Government of India Act. The Assembly completed its work and adopted the constitution in November 1949. The constitution came into force on 26 January 1950.

In the canonical account, the workings of the Constituent Assembly in Delhi, its debates and the texts it produced between December 1946 and November 1949, form the cornerstone of India’s constitutional thought. The long and rich debates and their resulting constitutional text also became the main source for how scholars have understood the founding of India’s constitution. Scholars, thus, explained the production of the constitutional text as a result of elite consensual decision making, or conflicts, which drove its framing and lent legitimacy to the text. They have also emphasised the transformative power of the ideas that informed the new constitutional structure or, to the contrary, stressed the text’s continuity rather than break from the colonial constitutional framework.8 In both cases, the voluminous debates, spread over 5,546 pages in a set of five books, and the constitutional text have formed the principal source for understanding the constitution-making process and its implications for India’s democracy.

This book offers an alternative story. It explores the making of the Indian constitution as it emerged outside the Constituent Assembly, driven by diverse publics across the breadth and length of India’s territory and even beyond it.

By turning our gaze away from the Constituent Assembly, Assembling India’s Constitution, offers a new history and a new paradigm for understanding the making of the constitution. The book reveals the existence of multiple, parallel constitution-making processes underway across the subcontinent, showing that the Indian constitution was not solely an elite exercise anchored in the Constituent Assembly in Delhi. From the sparsely populated Spiti and Lahaul region in the northern Himalayas to the small village of Kattunedungulam in the deep south, from the remote Chittagong Hill Tracts in the east to the numerous princely states of Saurashtra in the west, and even as far away as Stockton, California, diverse Indian publics debated the future constitution and made constitutional demands. Informed by their lived social realities and experiences, the Indian public deeply engaged with the future constitution. This was an organic process that emerged from below. The 5,546 pages of the Constituent Assembly debates represent, we show, just a tiny portion of the thousands of pages documenting the wide-ranging deliberations on the making of the constitution that took place outside the Assembly.