In many Indian households, rituals are not declarations of belief so much as acts of continuity. In this excerpt from Tell My Mother I Like Boys, Suvir Saran reflects on how childhood rituals, memory, and faith shape an enduring understanding of grief and belonging.

***

One of the earliest memories I have, as vivid as the sunlight piercing through the crack of a drawn curtain, is of a biscuit—a simple, sweet thing that was handed to me every morning by my grandfather, Bhagat Saran Bhatnagar. It was an unspoken ritual, a silent conversation. Before accepting the biscuit, I would always touch his feet—a small act of reverence. My tiny fingers would brush against his skin, and he would respond with a smile that was both a blessing and an embrace. The biscuit would crumble in my hands, its sweetness dissolving on my tongue, a fleeting joy that lingered far longer in my memory. That biscuit was more than a treat; it was a bridge—a bond that tied us together, a rhythm that whispered, I see you, I cherish you, you belong.

That ritual, so steady and so sure, came to an abrupt halt on a day that was to cast a long shadow over my childhood. My grandfather passed away in Agra, at the shrine of his guru. He died fulfilling what he believed to be his spiritual destiny. I was five at the time—too young to comprehend the finality of his departure—yet I understood, in the way children often do, that something monumental had shifted.

When we returned to our home in South Extension, Part 2, New Delhi, the house, usually bright with life, felt suspended in a kind of breathless quiet. My grandmother, Kamla Bhatnagar—Dadi—spent long hours in her prayer room, her hands trembling as she made her offerings. This room, her sanctuary, was filled with idols of all faiths: Krishna, Saraswati, Christ and Guru Nanak. Every morning, she would wake them with hymns, bathe them with water, adorn them with sandalwood paste and offer food at their feet. These offerings, prasad, were placed in my hands with a gentle instruction: ‘Feed the birds outside. They carry our love to the heavens.’

At first, I didn’t understand what she meant. But as I scattered the grains of rice and the pieces of bread on the ground and watched the sparrows, crows and pigeons swoop down and peck at the food, pausing only to look up, their wings beating as they soared higher and higher, something stirred in me. I imagined them carrying not just food but messages, invisible letters written in prayer, from us to those we had lost. My grandmother told me that our loved ones who had departed were always watching us, blessing us from above. The birds, she said, were the carriers of our love, our gratitude, our remembrances. ‘They take what we offer with humility, without ego, and return it to the heavens,’ she would say.

It was a rich metaphor, one that stayed with me for a long time. The act of feeding birds was not just about them. It was a way of understanding the cyclical nature of life, the seamless transition between the ephemeral and the eternal. It was about recognizing that life does not end with death; it transforms, continues, finds new forms. As I watched the birds lift into the sky, their wings glinting in the sunlight, I felt a strange kind of peace.

Years later, this memory would return to me in Bombay, when I lost a close friend to a car accident. She was young, full of life, her laughter still echoing in my ears when the news reached me. The world around me seemed to collapse in grief, but I couldn’t mourn her passing the way others did. I saw her not as gone but as living beyond that moment of impact. I imagined her soaring, like those birds I had fed as a child, lifted by the invisible threads of love and memory. Her passing did not feel like an end; it felt like the opening of a door.

In New York, I lost many more friends—friends who had shared their dreams with me, whose lives were cut short by cruel circumstances. Each loss could have broken me, but instead, they gave me strength. I became, as my mother had once been, a steady presence for others. I stepped into the spaces where grief lived, organizing, connecting, holding others while they broke. I had learnt, through those rituals of my childhood, to see death not as a void but as a continuation. Those who had departed were not gone; they lived on in the memories they left behind, in the movements they had begun, in the love they had shared.

***

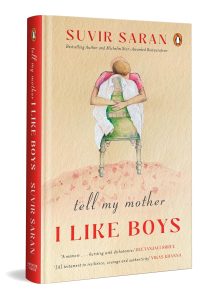

Get your copy from Amazon or wherever books are sold!