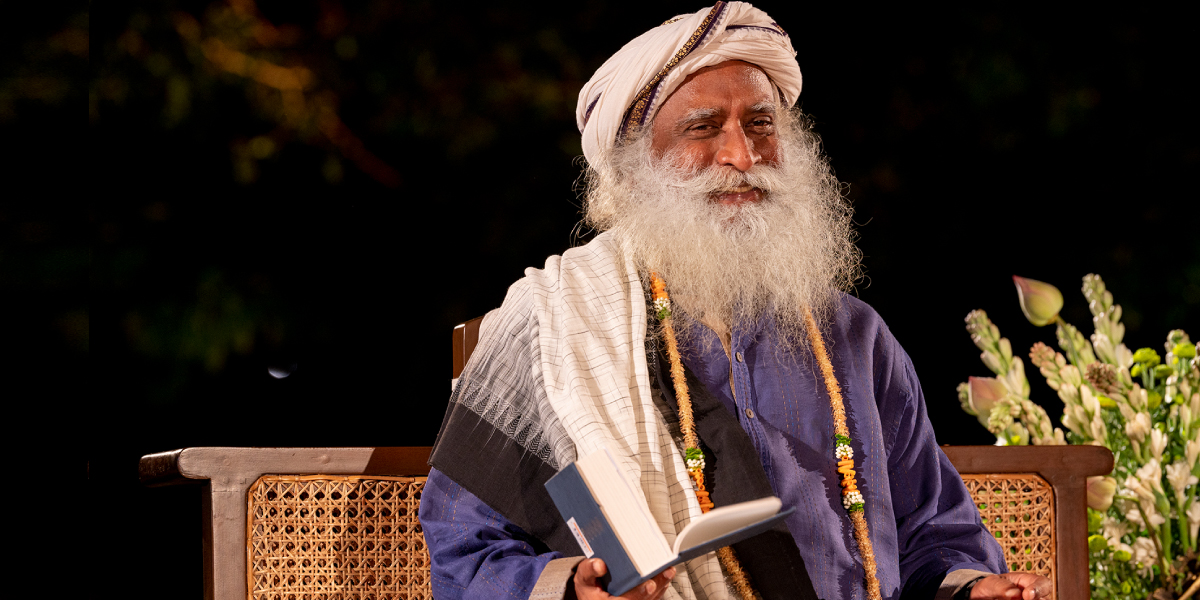

Sadhguru, the yogi, mystic and visionary, is a spiritual master with a difference. He has smitten the world not only in spiritual matters but with his business, environmental and international affairs along with his ability to open a new door on all that he touches. After having founded the Isha Foundation and penning down various books on spirituality and wellness, he has now brought out a poetry book called Eternal Echoes.

Eternal Echoes is a compilation of poems by Sadhguru written between the time period of 1994 and 2021. These poems cover every aspect of his life and travels ranging from nature, environment, human nature and the resonances he has felt during three decades and more. Seemingly simple at first, one begins to understand the hidden layers within these poems slowly and the meanings linger on.

Here is an exclusive excerpt, the introductory note to the poems in his book, where Sadhguru explains what made him turn to poetry:

*

Poetry is an in-between land between logic and magic. A terrain which allows you to explore and make meaning of the magical, but still have some kind of footing in the logic.

When people experience something beautiful within themselves, the first urge is to burst forth into poetry. If you fall in love with someone, you start writing poetry because if you wrote in prose, it would feel stupid. You can only say logical things in prose, but you can say illogical things in poetry. To express all those dimensions of life which are beyong the logical, poetry is the only succor, as it is the language which allows you to go beyond the limitations of logic.

As a child and youth, my mind was so unstructured and untrained that I could never find a proper, logical, prose expression. Naturally, poetry became so much a part of my life.

My poetry first found a big spurt when I decided to start a farm. My farm was a very remote place, far from the city. I lived there alone for days, and sometimes weeks, on end without any contact with other human beings. At this time, I started writing poetry about pebbles, grasshoppers, blades of grass- just about anything. I found each one of them was a substantial subject to write about.

There was no power in the farm and around six o’clock in the evening it would get dark. I would stay awake till midnight, in almost six hours of total darkness. Somehow, I always found when your visual faculties are closed off, you naturally turn poetic. Maybe that is why we have heard of so many blind poets in the world. I am not saying that having sight should not evoke poetry- it has. But the nature of the human perception is such that is sees much more when the eyes do not see.

In about four months, during this dark period of the night in my farm, I wrote over 1600 poems. Unfortunately, none of these poems are with us today. I had written them on small sheets of paper that I found all over the place. I had kept a whole bunch in my car. Then there was a small fire accident where my car burned down and those poems got burnt.

The poems in this book are only what I have written in the last thirty years, since we moved to the Isha Yoga Center. I hope they find some resonance with you.

A poem is a piece of one’s Heart, hope your heart beats with it and knows the rhythm of mine.

Much Love & Blessings,

Sadhguru

*

This note by Sadhguru would surely entice you to pick Eternal Echoes and join him on his soulful journey, also serving as a keepsake which has a short poem for every day and every feeling you’re feeling.