Here’s an excerpt from Beyond the Syllabus by Ankur Warikoo — a straight-talking, no-rules guide to life for teenagers who want more than just marks.

***

Get your copy of Beyond the Syllabus on Amazon or wherever books are sold.

Here’s an excerpt from Beyond the Syllabus by Ankur Warikoo — a straight-talking, no-rules guide to life for teenagers who want more than just marks.

***

Get your copy of Beyond the Syllabus on Amazon or wherever books are sold.

In She Stood By Me, Tarun Vikash captures the chaos and charm of young love—long-distance calls, meddling friends, and the bittersweet journey of two people trying to hold on to each other when life keeps pulling them apart.

Wake up you fool, we are getting late,’ I yelled out but to no avail; Manish stayed sleeping. And why wouldn’t he? I have no doubt he had spent the entire night on the phone, trying

to convince his ex-girlfriend to accept him again.

There is nothing like self-respect in his life. He loves being around girls. Girls flatter him, he flatters girls and the cycle goes on. I hate it. Why? Because unlike him, I have no options. I am terrified of speaking to girls, not that there is anything wrong with that. Not all guys are extroverts. I had issues talking to girls in the past and I have issues even today.

I hate myself for being like this but I hate Manish too. Last night, he spoke to the only girl I ever liked as if he had known her forever.

‘Manish, get up, for god’s sake? Look at your watch,

damn it,’ I shouted and kicked him hard enough to jolt him

out of bed.

‘Early morning and you’ve gone mad or what, Abhi?’ he

said, scratching his bum.

‘Look at your watch, you fool. We need to leave now to be on time.’

‘Oh please. I know why you are in such a hurry. You have to meet her. Isn’t it?’ ‘Shut up and get ready.’

‘And don’t you dare look at her the way you were looking

last night,’ I added. If I warn him, he might not do it but if I don’t,

he will definitely do it.

‘Now, don’t start again. I was just admiring her.’

‘Excuse me! Did you say admiring? Manish, you stare at

every girl like a jerk.’

‘Abhi, is that how you talk to your best friend?’

‘And is that how you look at the girl I like?’

‘Come on, Abhi. She is beautiful. Do you expect me to

keep my eyes closed and sit like a monk?’

‘Not monk, monkey, you must say. You barely behave like

a human when you see girls around you.’

‘What can I do if Aparna is beautiful? I just can’t

control myself.’

I felt like slapping him.

‘Whatever, but don’t talk shit when she comes today,’ I said.

‘It’s called being funny, damn it. You won’t understand.’

‘She is not your type and honestly, I have no idea why she

was even talking to you last night.’

‘Girls just feel comfortable around me and you are jealous

of that. Accept it.’

‘Oh, please. You and your dumb thesis on girls, I don’t

want to hear it. I beg of you. And listen, don’t make a mess

of things this time.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘After leaving the IIT centre, you are going to the station

to check for the return tickets.’

‘Why can’t you go?’

‘Because I have to drop her back home. I can’t leave her

alone with a jerk like you.’

‘Abhi,’ he growled.

‘Shut up.’

‘My Dad is her Dad’s best friend. You chose Dhanbad as our IIT centre because I told you. You should thank me for that at least.”

‘In your dreams,’ I said.

‘Don’t you dare ask me for any help now.’

‘Okay, fine. Thanks for everything and thanks again for making me choose Dhanbad as my IIT centre. But we are going back tonight and I only had last night to talk to her.

And you didn’t even allow me to do that.’

‘You guys did speak. Don’t forget.’

‘Yes, if saying “Hi” means speaking to a girl, then I did speak.’

‘Stop overreacting. You both are at the same IIT centre now. You can speak to her over there.’

‘You know, I can’t speak to her when I am alone.’

‘Be a man. Talk to her like I talk to girls. Look at me and learn something,’ he said.

I looked at him, feeling disgusted.

‘It’s okay. I will see what to do,’ I said.

‘I can help you if you want.’

‘You have already helped me a lot, Manish. So, please stay away from her.’

‘Okay, fine. I will try.’ ‘What the hell do you mean you will try?’

‘What do you want me to do, Abhi? You know me. Beautiful girls are my weakness.’

‘Manish, I am begging you.’

‘Okay, all right. I will not speak to her.’

‘She is coming soon. You know what you have to do.’

‘Yes, I have to sit in the front seat and you both will sit in the back seat,’ he said, pulling his blanket over him and going back to sleep.

***

Get your copy of She Stood By Me on Amazon or wherever books are sold.

In this excerpt from It’s Okay…, spiritual guide Jaya Kishori reminds us that true positivity isn’t about pretending everything is fine—it’s about accepting our pain, being patient with ourselves, and trusting that dark nights always lead to brighter mornings.

It’s Okay To Not Be Okay!

The other day, I was at a get-together that was attended by a sizeable number of people. I could spot some known faces, a few were friends, others with whom I have worked in the past, all mingling among themselves, amid a sea of unknown faces. They were greeting each other rather warmly, asking one another about how they have been, how their life was going. Most were responding in a very similar manner and tone, that ‘things were fine and that they were doing well’. Being in close proximity, I was able to overhear a few of these exchanges, when a question arose in my mind, ‘Was it a fact that they were indeed doing fine?’ ‘Could it be possible that there be someone in the world with whom all things were good and fine in life?’ ‘And that nothing was wrong in their lives,’ ‘No work or task of theirs was undone’. ‘That all or every of their relationships was good and none was troublesome or poor?’ To me, it seemed impossible.

Then it occurred to me that they, quite like me, were following an old lesson we learn when still young. When we are often advised by our elders:

• No matter what, you ought to be bold in the face of adversity

• You must always smile, even though you are hurting inside;

• You must not feel too sad about anything • You cannot afford to lose in life • You cannot get tired so easily;

• No matter what’s happening with you in your life, you must say, ‘It’s all okay.’ But the truth is, you are not!

In life, everything does not always go as we wish it to and to acknowledge this truth is our greatest strength. We tend to exaggerate and make a problem much bigger when we refuse to accept it. Life never runs perfectly; it is possible that on some days I don’t feel okay; which I believe is perfectly okay. When will we realize that ‘it’s okay –to not be okay’.

It is not necessary to be strong all the time; like it is not essential to smile at all times. If you are faced with problems in life, you must bear with it—but it is important that you also remind yourself that ‘things are not good’ and that ‘they are not running as you may have wanted’. Once this is done, you would perhaps be able to find a solution to the problem. If you keep feeding yourself with false beliefs about positivity that ‘Everything is going fine’ and that ‘You really do not have any problem’, then somewhere down the line, you are deceiving yourself. There is an increasing reliance and optimism that if you shoo away a problem or difficulty saying that nothing is wrong, or the problem or difficulty does not exist, you are relieved of it. This is one great fallacy. For the one in pain feels the pain, and no matter what is being said or needs to be believed, the pain does not subside on its own. This circumventing behaviour does not solve the problem. On the contrary, because you are not able to express the emotion, it becomes an added problem which is self-created.

The right way is to acknowledge that if you are in a given situation, then accept that you are in it. To be patient with that emotion is also a way to solve it. Remember, you are not the only one who is feeling this, there are numberless who are in the same boat— rather, most of humanity subsists in this. No one’s life is perfect, no matter how perfect they depict their lives to be on social media, it is far from that. However, not everyone has the courage to accept this fact. Maybe, you could try to do that? Not for anyone else but yourself. To realize that real positivity is not in ignorance but in acknowledgement. It is not about ignoring or running away from a problem but in accepting it.

I know it is easy to say such things, but difficult to live. I also know that if you are facing a difficult situation, you wish you could get out of it. I also know when a person is sad, he barely understands words of wisdom because of his pain and trauma. However, when one is in such a situation, one only needs to remind oneself that such a situation will not stay for long; it is only a passing phase. No situation stays permanently. The problem with which you were concerned or worried, say, five years ago, are you still worrying about those things? So quite like that, even the present ones would dissolve. Until then, we ought to learn to live with them. Therefore, it is important that we feel their presence and learn from them before they pass away.

At that time, you ought to keep reminding yourself, like morning follows night, your dark days will also end with a bright dawn. And if you wish to see that beautiful dawn, you must also experience the night. It is a matter of outlook; some enjoy the night and find it soothing; others are scared of it. So when you know that you need to pass the night, it makes a lot more sense that you pass it with a sense of tolerance and patience. Who knows, it might help to make your morning a little more beautiful than you had imagined. So it’s okay to not feel okay, but not okay to suppress those emotions and act as if everything is okay.

Know the hard times shall soon pass Though long and dark is your night; Be patient and have some faith A new dawn shall bring forth light.

***

Get your copy of It’s Okay on Amazon or wherever books are sold.

In this excerpt from Human Edge in the AI Age, Nitin Seth explores the unstoppable rise of Artificial Intelligence—and why rediscovering our uniquely human strengths may be the only way to thrive in this new era.

AI IS REDEFINING EVERY ASPECT OF LIFE AND BUSINESS

The Irresistible March of the AI Age Nothing else in the world . . . not all the armies . . . is so powerful as an idea whose time has come. —Victor Hugo, French author, poet and politician

AI’s time has come. It is all around us. It is unavoidable. AI might have sounded like pure science fiction, synonymous with futuristic robots or sci-fi movies a decade ago. It felt distant, something reserved for advanced research labs or tech giants. But here we are, on the cusp of a new era, where AI is woven seamlessly into the fabric of our daily lives. From the way we communicate, work and shop to the devices in our homes, cars and even our pockets—AI is everywhere, empowering us like never before.

Today, AI isn’t just a concept of the future; it is an undeniable force shaping our world. Whether we are asking virtual assistants for weather updates, relying on smart devices to adjust the lighting in our homes, navigating traffic with real-time insights or even having AI draft a business email—AI is present, indispensable and, quite frankly, extraordinary!

While AI has been brewing in the labs of tech giants and researchers, the advent of Gen AI has been an enormous leap forward in the history of AI. Unlike earlier forms of AI, which primarily relied on structured datasets and rule-based programming, Gen AI comes with a transformative ability to harness the data of the world and generate content, learn, adapt, create and evolve in real-time. It has shifted the narrative, transforming AI from a reactive tool into a proactive asset, ushering in a wave of innovation that feels limitless.

AI’s meteoric rise is no accident. While it has exploded on the scene quite recently, witnessing near-blinding adoption rates across all industries, it wasn’t possible without multiple waves of technology developments and business model innovations that have happened in the past.

Multiple waves of innovation leading to the AI age.

In my previous book, Winning in the Digital Age, I defined the digital age as a wide-ranging set of technology trends that have evolved over time. Each wave of technological evolution—whether it was the rise of the internet, the surge of mobile technology or the advancement of machine learning—has layered another block onto the foundation of AI as we know it. Business model innovations, too, have played a crucial role, as companies worldwide have eagerly embraced AI to enhance everything from operations to customer engagement. The AI we have today isn’t a standalone invention, but a culmination of countless innovations and relentless progress, each breakthrough building on the last until AI became an unstoppable force. Let’s look at the multiple waves of innovations that brought us to the AI of today.

It all started with the transition from physical to digital.1 Digital truly took off in the 1970s, when the world moved to digital with the explosive growth of computers and the availability of compute power. This era saw innovations like mainframe computers, by companies like IBM, and the development of the microprocessor by Intel, laying the groundwork for personal computing. These early advancements in computing and processing power created the essential foundation for AI, enabling the complex calculations and data processing that AI relies on today.

The next major wave arrived with the internet in the late 1990s, ushering in the dotcom boom. Companies like Amazon and eBay transformed retail by moving commerce online, shifting businesses from brick-and-mortar to e-commerce and online services, and redefining customer interactions and operations. Then in the late 2000s, social, mobile, analytics and cloud (SMAC) technologies emerged, reshaping interactions through social media platforms like Facebook, while the iPhone heralded the smartphone revolution, ushering an era of any-time, anywhere access to information, transforming the way people connect, work, shop and entertain themselves. Cloud services like Amazon web services (AWS) offered scalable infrastructure and big data analytics provided real-time insights. This internet and e-commerce boom are the predominant contributors to the rapid expansion of the amount of digital data, which became essential for training AI and improving machine learning methods.

Following the SMAC wave, the digital ecosystem era emerged, characterized by interconnected platforms like Apple’s App Store or Alibaba’s marketplace. These ecosystems enabled new business models and transformed industries and customer engagement. For example, companies like Netflix and Uber emerged that built new digital-first business models, which have led to the creation of new industries. These digital ecosystems also created a connected network where AI could be deployed widely, enabling companies to build AI-powered solutions that work across different platforms and services.

The early 2020s saw the advent of AI, built on a foundation of powerful new technologies like advanced computing, vast data availability and cloud infrastructure. This era also saw the rise of other new technologies like blockchain, the internet of things (IoT) and quantum computing. While blockchain enabled significant innovations like Decentralized Finance (DeFi) and transparent supply chains, IoT made connected smart homes and industrial machines a possibility. Quantum computing has now opened doors to solving problems beyond the reach of classical computing.

Today all these cutting-edge technologies are converging, opening up newer and greater possibilities for innovation. Their convergence is setting up the stage for new forms of intelligence and interconnected solutions that are not only making our lives easier but are capable of tackling long-prevailing real-world problems. However, amongst all these new technologies, AI has exploded exponentially in recent times. Let’s delve deeper into what made this possible.

Gen AI, the inflection point of the AI wave

The tipping point for AI came with the advent of Gen AI, which literally exploded on the scene, capturing the public imagination. The advent of Gen AI brought the powerful ability to generate rather than merely analyse or predict. This leap has been enabled by access to vast amounts of global data, advancements in algorithms and significant enhancements in computing power. These factors have empowered systems to learn from extensive datasets and perform highly complex calculations, enabling the creation of innovative content and solutions across a broad range of applications. It has unleashed the true transformative power of AI, catapulting it into not just the most groundbreaking technological breakthroughs of the digital age but perhaps in the history of human evolution.

The advent of Gen AI didn’t just open new doors, it broke down the walls that kept AI confined to the labs of researchers and big techs. With the power to create, not merely analyse, Gen AI has triggered a shift towards accessibility and versatility, making AI a tool for everyone, not just specialists. Let’s see how.

Expansion and democratization of AI

Over the past decade, due to data availability and quality, AI’s application was limited. Early AI implementations in healthcare, for example, focused on tasks like detecting anomalies in medical images, such as identifying tumours in X-rays. AI systems required large, high-quality datasets to perform well, which were often difficult to collect and curate. This limited AI to isolated cases, like image recognition in radiology and prevented broader integration in solutions like diagnosis or personalized treatments. The lack of deep and high-quality datasets also restricted AI in other fields. The advent of Gen AI has transformed this paradigm in two major ways. First, it has led to the expansion of AI. As I mentioned, AI needed big, high-quality datasets to work effectively, which was hard to get to and hence really limited what it could do. Gen AI’s large language models (LLMs) are trained on vast, diverse datasets sourced from the internet, literally the data of the world. This gives Gen AI the ability to provide reasonably accurate initial responses (often 40–60 per cent) to nearly any question. This breakthrough means AI’s dependence on data as a starting point has been significantly reduced. Since these models are built on a massive pool of existing knowledge, they excel at recognizing patterns and relationships, enabling them to generate accurate responses across a wide range of topics. This means we no longer need to build AI models from scratch. Instead, we can leverage these pre-trained models and fine-tune them for specific applications, dramatically lowering the effort and time required for developing AI solutions.

Second, tools such as ChatGPT have democratized AI, making it accessible to people without technical expertise. These tools have simplified AI interaction through easy-to-use interfaces that respond to natural language prompts, removing the need for coding or specialized knowledge. This accessibility allows even the nontechnical users to leverage AI for tasks that required a decent level of expertise in the past. Now, individuals from all backgrounds can use AI interactively for tasks like creating art, drafting essays, generating recommendations or even writing codes. For instance, a small business owner can produce custom marketing materials with simple prompts, and a remote teacher can design tailored lesson plans without extensive resources. This evolution has made AI versatile and practical for everyone, regardless of background or expertise. While we discuss the remarkable capabilities of ChatGPT, it wouldn’t be fair to not acknowledge the role of OpenAI in bringing the advancements of Gen AI from the realm of scientists to the masses. So let me take you through their journey and their role in democratization of AI.

***

Get your copy of Human Edge in the AI Age on Amazon or wherever books are sold.

In this heartfelt excerpt from How to Stop Overthinking Forever, Rithvik Singh reflects on his own journey of friendship, heartbreak, and self-worth — and shares a reminder we all need: you deserve people who truly value you.

Back in fifth grade, a day before Friendship Day, I remember my mother asking me how many bands I needed but I didn’t have an answer. She got me five bands regardless, but I only had one friend. The next day, I wore four of the bands to school so that everyone thought I had many friends and saved one for the only friend I knew I could give the band to. But when I offered him the friendship band with a smile on my face, he didn’t smile back. I realized he didn’t have a friendship band for me. ‘

I’m sorry, I only brought bands for my close friends. Let me see if I have an extra one,’ he said. I still remember his landline number; we went in the same school bus together and talked all day long, but he still didn’t consider me a friend. It shattered my heart. In the seventh grade, I made a friend who told me that while we could be friends, we could never be best friends, because he already had one. I thought we were best friends. When I switched schools in the eighth grade because my mother was transferred to another city, I thought to myself, this is the fresh start you were looking for. You’ll find friends here. I yearned for friendship with all my heart, but I just couldn’t make friends. Although I loved the school and the teachers, and talked to a lot of my classmates, I couldn’t find anyone I could truly consider a friend. In the eleventh standard, I switched schools again, because yet again, my mother had been transferred to another city.

This time, I went in with no expectations. But from the very first day, I realized people were warmer and nicer to me. I was still the same person who couldn’t make friends, but in that school, people were genuinely interested in talking to me. My best friend from the same school recently travelled for over 400 kilometres to surprise me at my book signing. Another friend of mine sends me presents every birthday, even though she lives in another country. Another one gives me a handwritten letter every time we meet. I now have friends who check in on me regularly, genuinely care about my success, want me to grow in life and love me wholeheartedly.

The point is, sometimes you cannot find the people who understand your heart, not because you’re the problem, but because you’re not surrounded by people who are like you. I kept wondering if I was boring or annoying or unworthy of being loved until I found people who made me feel loved without me having to ask them for it. It took me a long time, but I eventually found genuine friends whose sense of humour, mindset and hearts matched me. I conducted a poll online asking people if they believe their friends secretly dislike them. The results were shocking. Out of the 4811 participants, 3827 (79.5 per cent) believed their friends secretly disliked them. Only 984 (20.5 per cent) participants said ‘no’.

If you feel insecure in your friendships, this is your reminder that you’re not alone. So many of us feel the same way. We feel alone even when we have a lot of ‘friends’—mostly because we’ve not found the right set of people yet. If you’re someone who constantly overthinks because you do not have friends who feel like home to you, please know that you will find people who will cherish you for who you are and appreciate all your efforts. Just because you have been betrayed by people you thought were your friends in the past doesn’t mean you’ll be betrayed by everyone you come across in your life. I was ‘friends’ with people who didn’t return my calls, didn’t invite me to hang out with them, didn’t believe in my potential, didn’t laugh at my jokes and didn’t value my efforts. And I realized over time that I didn’t lose them. They lost someone who genuinely cared about them.

They lost someone who simply wanted a corner in their hearts and was willing to do anything for them in return. I didn’t stop giving my best in friendships because a bunch of ungrateful people don’t get to shape my perception of friendships. I knew I wasn’t the problem. I knew I’d find people who’d love me for thinking differently from them instead of judging me for it. People who’d understand my jokes and believe in my dreams. People who’d hate to see me hurt. People who’d hold my heart gently on my worst days. Sadly, what happens when you’re giving your best in a friendship and it’s not being reciprocated is that you begin to wonder what’s missing in you. You see them making efforts for other people and wonder what makes them better than you. But when you start realizing that the feeling of gratitude is rare and that not everyone knows how to value people, you stop getting affected by ungrateful people who couldn’t ever value your friendship. If someone thinks you’re not cool enough to be their friend, don’t be their friend.

If someone thinks you’re boring, let them find interesting people. If someone thinks you’re too sensitive or too clingy, let them choose someone who isn’t. You deserve friends who will love you for who you are and respect your feelings. Friends who know how to be gentle with your heart. This is what you need to remember if you’re yet to find genuine friends:

• Your worth isn’t determined by the size of your friend group.

• Your worth isn’t determined by the number of people who find you ‘interesting’.

• Your worth isn’t determined by the number of parties you’re invited to.

• Your worth isn’t determined by what you do on Saturday nights.

• Your worth isn’t determined by how many people sit with you during lunch breaks.

• Your worth isn’t determined by the actions of someone who doesn’t see the value of your efforts and always takes you for granted.

If you’re someone who truly cares about people— you’re there for them when they’re unwell or upset, you try to make their birthdays special, you try to keep in touch and make plans, you give them advice whenever they ask for it, you believe in their ambitions, you don’t say bad things about them behind their back, please know that you deserve friends who do exactly the same for you. And if, despite doing all this for your friends, they’re unable to see your worth, letting go of them is a prerequisite for restoring your self-esteem and confidence.

Always remember:

• If someone really cares about you, you will not overthink because of them. They will not make you anxious. They will not drain your energy. They will not make you feel bad about yourself.

• If a friend is making fun of you in front of others, there’s a huge possibility that it’s not a friend but a secret hater. Friends are supposed to pull each other’s leg in private, but yell at the top of their lungs to support their friends in public. You do not have to settle for being the laughing stock just because you’re scared of being alone.

• People will suggest that you shouldn’t have expectations in friendship. They will talk about low-maintenance friendships, but never forget that there’s a difference between low-maintenance friendships and low-quality friendships. Someone can be miles away from you and still manage to support you from a distance, and someone can be right next to you and still make you feel unwanted.

When you’re doing a lot for someone and they make you feel unwanted in return, you keep overthinking what exactly you have done to deserve the cold treatment, the ignorance, the neglect. If nobody has said this to you before, let me say it to you right now: you do not need to overthink because of someone who doesn’t care about you. Someone who is determined to ignore everything you do for them. Someone who always chooses other people over you. You deserve to feel loved, heard, appreciated and understood, and if a friendship doesn’t come with that, it’s not friendship at all.

***

Get your copy of How to Stop Overthinking Forever on Amazon or wherever books are sold.

In The CEO Mindset, corporate leader Shiv Shivakumar breaks down what it truly takes to succeed in the corner office—and why developing a CEO’s way of thinking starts long before you get the title. Read an exclusive excerpt below!

I teach regularly at business schools across the world. In India, when I teach, I ask the students a simple question: ‘Who amongst you aspires to be a CEO?’ Nearly 90 per cent of the class put up their hands. After the aspiration to be a CEO, many want the next best—to be entrepreneurs. In the West, the students are keen to know about emerging industries, and they always come to me with some idea or other they are working on. They ask me to pick holes in their ideas. There is certainly a near universal fascination among young people for the role of CEO, whatever the reason behind it— maybe aspirational, or maybe a measure of their confidence or security. It is much more in India than other parts of the world where I teach, maybe because we are a developing economy where many opportunities have come up in the last two decades, maybe it’s the adoption of technology skills, etc. It is also a factor of media coverage. In India, businesses and CEOs are given a lot of coverage. In the Middle East, for example, it’s much more about the sheikh and his people. In the USA, maybe it’s the greater risk appetite that inspires everyone to

want to be a startup CEO.

The CEO is clearly an aspirational role, viewed from the outside. When I quiz students and young managers about the reason they want to be a CEO, they invariably come up with

three: to acquire status; to acquire power; to make money. I personally feel this is a narrow, material list of reasons. Maybe this list was understandable in a past world where roles and responsibilities in the corporate world were easier to define. But the role of the CEO has considerably evolved over time.

Let’s see how the role began and how the term itself came into use.

The role and designation of CEO, or chief executive officer, first came into use over a century ago. The term was first used around 1914 in Australia. In the USA, it began to be used only

around 1972 in the business context, but it actually came into being in 1782, when the designation of chief executive officer was used to describe the governors and other leaders in the executive ranks in the thirteen colonies of the British in America.

In India, the early district collectors were working as CEOs of their districts—they had a tax target, information-gathering targets and development targets. The current role of CEO has evolved to meet the higher demands of corporate shareholders. The shareholders place emphasis on financial and competitive metrics for their companies, and the CEO is responsible for them. This is very different from when the role began in corporations. So, though the title remains the same, the demands and skills needed for the role have changed significantly since the advent of technology, globalization and changes in regulation. I think technology has made everything more centralized in governments and corporations.

You need to be of a certain mindset to fulfil the role of CEO. But you don’t develop this CEO mindset upon getting the CEO job. You display elements of the CEO mindset in every job starting with the junior roles you take on in any organization.

I label this CEO mindset as C H A R L I E.

It stands for:

Communication

Holistic thinking

Absolute standards

Reframing of issues

Legacy thinking

Investing in people

Ethical execution

A good CEO mindset, according to me, starts with holistic thinking. No other job in a company offers you the leeway to think wide, get into depth of matters when needed and create across-the-board impact. So, how does one learn to think like a CEO? A basic MBA degree teaches you organizational design and the nuances of being a CEO. You learn the nuances by preparing and debating case studies, which are invariably about a problem faced by a hypothetical CEO. However, that’s a theoretical structure. The real world does not follow the guidelines of a case study.

When you are a junior manager, what you essentially deliver to the company revolves around execution metrics.

While you execute for results, do also think about the larger aspect of what’s happening around the job you are executing. Ask yourself how you can reshape the job with your skills

and thinking. When I was a sales manager in charge of beverages and soft drinks at Unilever, we tended to think of soft drinks distribution as akin to distribution of soaps, detergents and

tea. Nothing was farther from that. We were failing miserably. I reached out to Krishnaswamy who was sales manager of Campa Cola in Chennai and requested him to teach me the fundamentals of soft drinks distribution. I then realized that soft drinks distribution needed to be expanded and contracted depending on the season. I learnt that inventory

at a soft drinks distributor is dead inventory.

The only place for inventory of this product is on the retail shelves. Armed with these learnings, I nervously proposed to Hrishikesh Bhattacharyya, the director of Unilever India that we should trim our inventory to three days’ and only drive visibility on the shelves. He quizzed me, asking me where I had learnt

these new principles. After listening carefully to what I had to say, he approved the plan I suggested. Our sales tripled in

the next few months. The learning you can have from this episode is that if you want to think holistically, your organization and your industry are the wrong place to start. Your company and your industry have done the same thing for years, and the people there are rewarded for not rocking the boat. Some things may stay the

same, but most things change.

Whenever we asked the retailer how we (the FMCG company I worked for) could challenge Nirma in detergents, he would say introduce a yellow detergent powder. Whenever we asked the retailer how to fight Colgate, he would say introduce a mintier toothpaste. Current industry people can only give you their views, which are based on the past. They can never look ahead. If you want to look ahead and think holistically, then speak to people in other industries, ideally leading-edge industries, and you can bring the concepts and business models

from that industry to your own doorstep.

***

Get your copy of The CEO Mindset on Amazon or wherever books are sold.

In Bhairavi, the second book of the Maha-Asura series, Prakash Om Bhatt takes us from the blood-soaked battlefields of Tretayuga to the shadows of modern-day India, where gods, demons, and humans are all pawns in a deadly cosmic game. Read an excerpt below!

Naari

Tretayuga

Lanka

The killing of Sita had led to a deafening silence in the camp. Not only Sri Ram, but the entire army of apes, along with Hanuman, Lakshman, Sugreev, Nala, Jamabavat and others, felt the clasp of rage, agony, sorrow, anguish and pain in their hearts. ‘Brother, we shall avenge every drop of blood spilt from Maa Sita’s body!’ Lakshman, adrenaline rushing through his veins, declared as he put his hand on his elder brother’s shoulder. ‘Lanka will be destroyed!’ ‘That scoundrel will pay for his sins!’ Hanuman said, clenching his fist. ‘Indrajit will be dead, O Lord!’ Just then, Vibhishana, the son of Vishrava, entered the camp. He could sense the thick tension in the air. He comprehended the entire situation as he looked at the bodiless head of Maa Sita lying on a rock, and then at the distress on everyone’s face. ‘Maharaj, I didn’t think you would have fallen for the dubious scheme of Ravana’s son!’ Vibhishana said in a sympathizing tone. ‘What you think is Maa Sita’s head, is simply a deception!’ ‘Deception?’ Hanuman asked, flabbergasted.

‘I have known Indrajit since before he learnt to walk. I am well aware of his crooked schemes and deceitful plans!’ Vibhishana said as he took the head of Maa Sita in his hands. ‘To ensure that Ram and his army grow despondent before the war, Indrajit has created this optical illusion with the help of the great illusory asura, Vidyutjihva. My spies have just confirmed that Maa Sita is still in Ashokavatika, the garden with the Ashoka trees!’ ‘What is the reason for doing this right now?’ Ram sneered, almost shouting the words at Vibhishana, Ravana’s younger brother. ‘The point is . . .’ Fear lurked in Vibhishana’s eyes as he said the next words. He lowered his voice to a whisper. He knew that only the people present in this camp had the ability to stop the catastrophe Ravana was about to bring to the world—a secret that would mutate the future of the universe.

Present Day

Coimbatore

There was a light murmur in the air, indicating that the birds would soon fly away to find food for the day. The midnight blue of the night was gradually fading away. The golden glow of dawn was about to paint the sky. Bhairavi Maa, Sadhvi Maa, Manasvi and ten other faithful devotees reached the enormous 112-feet idol of Adiyogini. Everyone bowed to this Mahayogini; she represented all the sixty-four yogini forms of the Devi. ‘ॐ नमश्चण्डिकाायैै! Om Namashchandikayai!’ Bhairavi Maa folded her hands as an expression of gratitude for her devotees and said, ‘You may all rest now.’ Everyone, except Sadhvi Maa and Manasvi, bowed down to her and started walking towards their huts. And the trio of Bhairavi Maa, Sadhvi Maa and Manasvi walked for about a kilometre to arrive at a private chamber of the ashram where none of the disciples or devotees were allowed. They walked through an enormous gopura, the monumental entrance of a temple. There was a naagbandham—literally, the bond of the serpents—figurine on the gopura. On crossing it, they reached a temple-like structure, beside which stood a small hut. A six-feet-tall trishul, or trident, had been wedged into the ground at a forty-five-degree angle in the courtyard of the temple. Numerous trees, small and big, lent a sense of serenity to the place.

It seemed as if it would need three or four people to open the wooden door of the temple. There was the ॐ carved on either panel of the door. Bhairavi Maa looked at Manasvi and Sadhvi Maa. Taking the cue, they went inside the hut to get a huge salver laden with a variety of fruit. Sadhvi Maa and Manasvi held the platter, which weighed almost eight kilos, with both their hands. Reaching the gate, Bhairavi Maa assumed the yoni mudra, a hand gesture to call upon the Mother Divine, and started the chanting of the beej mantras, the seed syllables.

‘लँँ . . . वँँ . . . रँँ . . . यँँ . . . हँँ . . . ॐ . . . ’ ‘Lam . . . Vam . . . Ram . . . Yam . . . Ham . . . Om . . .’ Sadhvi Maa and Manasvi joined her in the chanting. ‘लँँ . . . वँँ . . . रँँ . . . यँँ . . . हँँ . . . ॐ . . .’ ‘Lam . . . Vam . . . Ram . . . Yam . . . Ham . . . Om . . .’ After chanting the beej mantras thrice, Bhairavi Maa raised her hands in the air and the doors opened without being given the slightest nudge! Before stepping into the temple, the three women bowed their heads in obeisance. This had become a daily routine for the three of them. Manasvi and Sadhvi Maa knew a secret that even the closest devotees of Bhairavi Maa had no inkling about! ‘Amma,’ Manasvi’s voice was laced with worry. ‘The agitation is quickly growing. Isn’t it?’ Bhairavi Maa remained silent as they walked a few paces before coming face to face with the deepest secret and the most mysterious aspect of Shakti Ashram. It appeared as if their arrival had been awaited for hours.

Present Day

Rajkot

The city of Rajkot was about to hit the sack. The dulled sound of the winter winds filled the otherwise quiet hour. The truck had stopped about an hour ago on the university road to make a delivery. Before the driver could finish the formalities and unload the sacks of wheat, Riya jumped out of the back. This caused her wound to start bleeding again. But who had the time to tend to the physical injury right now! The garden in front of the famous love temple was bustling with people. Riya was still wearing Hamid’s jacket and cap. It would be foolish and dangerous for her to start her journey towards Vasant Niwas before the city slipped into slumber. She had no option but to wait. She found a secluded spot in the garden, put her cap on her face and sat there quietly for about an hour. The city seemed unaffected by worldly affairs, and exuded peace. At around 9.30 p.m., when it was nearly time to shut the garden to visitors, the guard went around requesting everyone to leave. Riya, trying to be as inconspicuous as possible, walked out of the garden. With a careful stride, she entered the nearby Mayur bookstore. Though there was no customer in the store at this hour, from the body language of the store owner, it was evident he was not going to shut down anytime soon. She did not have any money, so she wouldn’t be able to buy anything. However, she had to pass her time, and so Riya picked up a month-old Bharat Today magazine from the rack. Coincidentally, the cover story was about the owner of a multinational company and the most eligible bachelor in the country. INDIA’S HEART-THROB AND GEN-Z’S INSPIRATION . . . VIVAAN ARYA! A photograph of Vivaan sitting on a royal throne was on the cover page. In the picture, he looked no less than an emperor born to conquer the world! Can someone who was an inspiration yesterday become a traitor today? Can the hero of the youth suddenly become the most wanted criminal in the country?

***

Get your copy of Bhairavi on Amazon or wherever books are sold.

In her book 21 Habits to Yogic Living, Juhi Kapoor shares simple yet powerful practices to transform your day—starting with this foundational morning kriya.

‘Every morning is a fresh beginning. Every day is the world made new.’ —Sarah Chauncey Woolsey Mornings are important, after all, it’s the start of your whole day ahead. So, how do we start it right? Well, there’s the standard—brush your teeth, take a shower, comb your head, get dressed. Is it enough?

In our bodies, the excretion process eliminates waste products such as feces, urine and sweat. If these waste products accumulate excessively or become imbalanced, they can contribute to the development of various health disorders.

Nothing against the humble shower, but it doesn’t do a thorough cleanse. In fact, if you are to embark on the path of yoga, cleansing is paramount per Ashtanga Yoga. One of the concepts in Ashtanga Yoga, saucha, which translates to ‘cleanliness’ or ‘purity’, is an essential niyama (rule) in the practice of yoga. It emphasizes the purification and cleanliness of both the external and internal aspects of our being.

Cleansing forms the foundation of our day—not just a warm-up or precursor to yoga, but an integral part of the practice itself. Kriya is a yogic practice to cleanse or detoxify. In this section, we will delve into four kriyas that to be inculcated as daily habits at the beginning of your day for cleansing the body and mind.

Habit 1/21: Jivha Mulashodhana

Time taken: 2 minutes

Jivha Mulashodhana translates to ‘cleansing the root of the tongue’. In Sanskrit, the term ‘jivha’ refers to the tongue, ‘mula’ represents the root, and shodhana signifies the act of cleansing.

In many traditional healing systems, including Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine, tongue analysis is an important diagnostic tool.

Cleansing the tongue is seen as a holistic practice that promotes overall well-being by supporting the harmonious functioning of the body’s systems.

The tongue is a significant organ in human development, closely related to the three germ layers: ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm. It plays a crucial role in intercommunication within the body. Additionally, the tongue holds cultural importance, symbolizing language, intellect, and verbal expression. Early texts of Chinese Medicine, such as the Ling-Shu Jing,2 recognized the connection between the tongue, heart, mind and spirit. The tongue serves as a diagnostic tool and an essential instrument for skilled physicians during examinations.

According to Ling-Shu Jing, the appearance of the tongue is closely linked to the internal organs. Here’s a summary of the relationships described [1]:

• The entire tongue corresponds to the heart.

• The kidney vessels terminate at the root of the tongue.

• The spleen vessels enter the body and reach the lower side of the tongue.

• The margin of the tongue is associated with the liver vessels.

• The tip of the tongue is connected to the lung and heart vessels.

• The tongue is related to the upper burner (heater), lung, large intestine, stomach and their respective vessels.

• The tongue is also connected to the lung and pericardium vessels through branches of the kidney vessels.

The significance of the tongue in the body becomes evident when considering its connection to various organ systems. Cleansing the tongue can have a far-reaching impact on overall health, influencing the functioning of multiple organs.

How to Practice Jiva Mulashodhana

1. Find yourself a basin or a sink.

2. Put your index and middle finger together and gently insert them in your mouth onto your tongue (pic 1.1). You have to reach as far back as possible to the back of your mouth, while also gently rubbing the tongue with your fingers. This may feel uncomfortable at first, and you may feel the need to regurgitate. But, you cannot stop here.

3. Continue rubbing in a manner that your fingertips are at the farthest corner of your tongue, while the finger is laid atop it. Placing your fingers carefully and as mentioned ensures the whole tongue is cleaned simultaneously. However, you have to stay at the farthest part of your tongue for as long as possible. With time, it will get less uncomfortable.

4. Naturally, after two to three trials, you may feel like throwing up, but these are only sensations triggered by a foreign object stimulating your digestive tract’s delicate openings. These convulsions are perfectly normal and, in fact, expected. After you are done, rinse and gargle.

5. You may notice a white residue sticking on your fingers. Make sure to clean well.

Benefits

• First and foremost, it cleans the tongue thoroughly.

• Did you know an unhygienic tongue is to blame for bad mouth odour? The tongue provides for a warm uneven surface, where bacteria can latch on leading to infections, unwanted white slime, and bad odour. Jivha Mulashodhana helps you shake their foundation and eliminate them from the roots.

• The tongue, a crucial muscle in digestion, is also remarkably delicate. You would notice just the touch of your fingers makes your tongue move, clench your jaws. And the farther you reach, the more sensations you experience. You will essentially be stimulating your food pipe and stomach, leading to an improved digestion.

• This technique helps to stimulate tongue function, which leads to improved digestion. When you pull at the tauter end of the tongue, you gradually increase its length and flexibility, which in turn helps move food particles around and promotes healthy lubrication.

• Jivha Mulashodhana not only removes residue from the taste buds but also stimulates them through a massaging motion, allowing them to fully experience sensations. Stimulated and exposed taste buds enhance your whole experience of a meal.

• The tongue can be a breeding ground for bacteria, and over time, as the impurities collect, they start to impact your food pipe and throat. Tongue infections have been known to spread as far down as your larynx. Hence, this kriya is a must do.

• The kriya also causes contractions in your stomach’s walls. These contractions further send nervous signals to your intestines to commence elimination. Thus, it is beneficial in getting rid of constipation and irregular bowel movements.

At this point, you may feel that this practice has been successfully replaced by the invention of U-shaped steel tongue cleaners and flexible toothbrushes, which claim to pluck out any hidden impurity.

But is this kriya an alternative to that tongue cleaner in your bathroom?

Jivha Mula Shodhana does not just clean the tongue, it also activates the organ systems.

That being said, neither is a replacement for either. Rather, each complements the other. You can continue cleaning your tongue with a tongue cleaner after you brush your teeth.

When to do it?

The best time to do it is first thing in the morning. Prior to doing any forms of yoga, doing cleaning is important. EVEN BEFORE YOU BRUSH!

CAUTION

• Practice empty stomach

• Use gentle pressure and avoid any harsh movements

• Make sure your hands are clean and disinfected before you start

• Avoid eating or drinking anything immediately.

Who should avoid?

The oral cleanse is a standard and easy-to-do exercise. Most people will find it easy once they get comfortable with the regurgitating sensation. There are no side effects. However, you may need to exercise more caution if you are suffering from any of the following:

• Hypertension

• Stomach irritation

• Cardiac disease

• Tonsilitis

• Cold or cough/respiration-related discomfort

• Mouth/tongue ulcers

In such cases, it is advised to use one finger and be gentler. Pregnant women should also avoid this practice if they experience nausea or morning sickness.

***

Get your copy of 21 Habits to Yogic Living on Amazon or wherever books are sold.

Read an exclusive excerpt from Secession of the Successful below!

The Indian diaspora, a heterogenous grouping of people of Indian origin (PIO) settled overseas for more than a generation, and non-resident Indians (NRI) who have emigrated in the post-Independence period, is both a natural phenomenon, arising from the migration of people over centuries, and a creation of recent historical and developmental processes, including European colonialism, global demographic shifts and the emergence of knowledge-based economies. More than half the population of what are referred to as ‘overseas Indians’ or the Indian diaspora, is comprised of PIOs. These are Indian-origin persons who are either descendants of Indian slave labour or of Indian communities settled overseas over along period of time, as traders, teachers or travellers globally spread out, from Fiji in the Pacific, to Mauritius in the Indian Ocean and to the Caribbean in the Atlantic, a large number of PIOs, now constituting over a dozen different nationalities, are the children of Indians exported as slaves or who travelled as managers, doctors, book-keepers and such like, working the plantation economies of the nineteenth century.

Through the early part of the nineteenth century, the UK and other European nations took half-hearted measures to abolish slavery both at home and in their overseas colonies. These high-minded actions, prompted by domestic political pressures, exerted a squeeze on the supply of labour across colonial territories. Demand for such labour was, however, on the increase across the world. The abolition of slavery and the slave trade placed in jeopardy the plantation businesses of the empire. From sugar to tea, rubber to cinnamon, British and European colonial possessions from the Pacific to the Atlantic and through the territories in between were in need of cheap, sweated labour. European planters and their financiers were all looking for a way to address this demand by ensuring supply. The door, to quote Amitav Ghosh’s character, Mr Burnham, had been shut in London. A window had then to be opened. Fortuitously for the empire and its masters, that window was opened in Calcutta.

Land, and what came with it, was aplenty for the imperial powers of Europe. What they lacked was adequate labour. That too sweated labour. It was this desperate need for captive labour, who could be worked to death on the hot and humid plantations of sugar, rubber and such like, that prompted a search across the plains of northern India. The export of labour from India, of the ‘Asiatick’, to the plantation islands of the British Empire began early in the nineteenth century. Archival records and family histories tell us of such labour export to British and other European colonies dating back to the early 1830s.4 By the late 1830s, reports had already reached India of the ill-treatment of such labour. Following such complaints, the Government of India formulated certain rules and regulations for the export of labour and, in 1837, appointed a ‘Committee to Enquire into the Abuses Alleged to Exist in Exporting from Bengal Hill Coolies and Indian Labourers of Various Classes, to Other Countries’.5 The committee met in Calcutta over a period of six months, from August 1838 till January 1839, recording evidence presented by shipowners involved in carting labour out of the Calcutta port.

This included merchants engaged in the export of labour, port officials and police officers responsible for the management and security of the port, and the likes of a doctor who travelled on such ships, a male labourer and a female attendant accompanying a British couple on a boat to Mauritius. One such labourer, Sheikh Manik, and an attendant, Bibee Zuhoorun, were among the few who returned home and so could be summoned for questioning by the committee. A total of 1061 questions were posed, over a six-month period, to the ten persons who had appeared before the committee. The testimonies of Sheikh Manik, Bibee Zuhoorun and Dr Abdoolah Khan, the medical doctor on board the ship Gaillardon, owned by Boyd & Co. of Calcutta, constituted a clear indictment of the methods used to secure and transport labour and of the conditions of their life and work on plantations in Mauritius. Defending their business interests before thecommittee, Calcutta’s European merchants claimed that Indian labour would not only secure better remuneration overseas but would also have an opportunity to see the world and widen their horizons, liberating themselves from the narrow confines of their insular and wasted lives.

***

Get your copy of Secession of the Successful on Amazon or wherever books are sold.

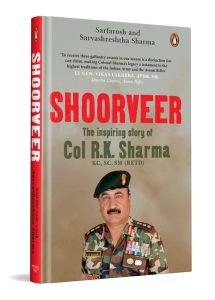

Read an exclusive excerpt from Shoorveer below.

In 1999, Pakistan began sending infiltrators to occupy the heights of Kargil and in turn, India began a major operation, known as Operation Vijay, to push them back. The Kargil War, as the operation is now known, was a turning point in the career of Raj.

The Indian Army pushed through the heights and beat back the Pakistani soldiers, and the valour and courage of its soldiers was a shining beacon for all of India. Raj was not far behind. Raj’s battalion had completed its tenure as a peace station in Hyderabad. By December 1999, they learnt that their next posting was in Kargil. At that time, the war hadn’t yet begun, so

it was intended to be a regular posting at first and Kargil, with its beautiful landscape and tall mountains, was considered to be an easier posting than the Kashmir valley. Major Ajit was detailed as the OC advance party for the move to Kargil, which was to transport all the military stores to Kargil, with Major G.S. Walia and Captain Hamir Rathore detailed with him. As the advance party’s movement was being prepared, Major Ajit appreciated Raj’s assistance on several occasions, boosting his morale. Before proceeding, Major Ajit handed over the company to Raj, giving him instructions to ensure a smooth mobilization and induction of the main body to Kargil. Major Ajit would also write regularly to Raj telling him about the welfare of the troops and details like the packing of materials and the type of clothing that would be required at Kargil.

At Hyderabad, a brigade-level handball competition was announced. Raj received instructions from the 47 Brigade that 22 Grenadiers had been detailed as a conducting unit for the competition. The advance party had already moved out and this would perhaps be the last sporting contest before the main body left for the war, so there were few objections from their side to conduct the event. The CO simply told them to get it done so that they could focus on their own move to the front. The Brigade staff wanted to milk them to the max before they left. So, Raj and Lt Sajjan were detailed as part of the team as officers were required to participate in the competition.

Raj was called in by Major S.P. Yadav to go and meet the Brigade Major to be briefed about the finals and the prize distribution ceremony. Raj went to the office of BM Major D.A.S. Lohamaror from the Bihar Regiment, where Deputy Quarter Master General Major Day from Mahar Regiment was also sitting. Both briefed him about what needed to be done for the evening. Major Lohamaror then told Raj that for the prizes, he could buy anything from the Canteen Stores Department (CSD) priced between Rs 80–100, but the prizes should look big. Raj searched two or three canteens but there was nothing in that price range. At his own CSD, Raj found a set of six Borosil glasses worth Rs 60 and a few sets of ladies’ underwear costing about Rs 30. Raj told the canteen NCO to count if they had fourteen pairs of glasses as well as the underwear. The NCO told him, ‘Sahib, we have enough and this will be in your price range too.’ Poor Raj couldn’t think and just to fulfil the condition set by the staff officer, he purchased both sets and directed an INT Section Havildar to make fourteen gift sets by pairing both together.

That evening, everything went well. Although the 17 Bihar team was very good and Raj’s team missed a few players who had already left with the advance party, Raj’s team won the final with a huge margin. When the time came for the prize distribution ceremony, the teams came up to receive the prizes for the winners and runners-up; but when the time came to give away the two referee prizes, the referee from Bihar was nowhere to be found. No one knew where he was, perhaps he was being taught the rules of the game by his team-mates! When he didn’t appear even after some time, the commander asked what the prizes were. He suddenly tore open one of them—and in his hands appeared a packet of ladies’ undergarments. He hurriedly pushed it back into the pack as there were women there too, but the expression on his face was enough to tell Raj that he had made a serious mistake and he quietly backed away from the scene. Besides, Colonel Mehr had also noticed it and the same expression appeared on his face, too. Soon after, Raj saw the CO and the BM discussing something in hushed tones.

When the group photographs had been clicked, Colonel Mehra called Raj to a corner with, ‘Kya karoon tera? What should I do with you?’ Raj very innocently told him that nothing else was available in that price range. ‘You should have just got men’s underwear. Why did you need to pack women’s underwear?’ the colonel told him angrily. When the other officers heard the story, they laughed and told Raj he was responsible for making his own life hell.

***

Get your copy of Shoorveer on Amazon or wherever books are sold.