The journey of a business-from a small start-up to a large company ready for an initial public offering-is fraught with pitfalls and landmines. To scale a company, one needs to do more than just expand distribution and ramp up revenue. From Pony to Unicorn lucidly describes the X-to-10X journey that every start-up aspiring to become a unicorn has to go through. The book effortlessly narrates the fundamental principles behind scaling.

Peppered with anecdotes, insights and practical wisdom, the book is a treasure trove of lessons derived from the authors’ rich personal experiences in both building and guiding several start-ups that went on to attain the ‘unicorn’ status and became public-listed companies. Here’s an excerpt from the book on some key takeways about human capital.

**

Of all the enablers of scale, we believe the people side is by far the most critical and nuanced. Poor understanding of the human capital is the single biggest reason for most promising start-ups, we know, getting derailed and coming apart.

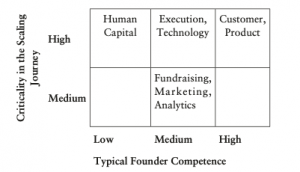

The table below captures our assessment of the typical founder competence in a domain vis-à-vis the criticality of the domain in the scaling journey. A deep understanding of ‘customer’ and ‘product’ perspectives are extremely critical for scale, but most founders understand these domains quite well. In fact, a start-up is almost always defined by the ‘product’ and ‘target customer’. Hence, most founders are well placed to navigate the challenges that crop up in these areas from time to time. In contrast, most founders do not have sufficient understanding of human capital issues. The simple reason for this is that most learning in this domain tends to be experiential. Therefore, given the criticality of human capital and the relative ineptitude of most founders in this domain, it often ends up as the ‘Achilles heel’.

We have identified some of the most common human capital questions and challenges that start-ups face during the course of their journey of scale, and the choices in front of them.

Here are the key takeaways about human capital

- Lateral hiring is inevitable. What normally breaks is the assimilation of lateral hires and their seamless collaboration with the home-grown rock stars. it is important to get this piece right. Conflict between these two groups has been the nemesis of many a good start-up.

- Too few or too many lateral hires are bad. Getting the optimal mix and number is important.

- It is key to hire the right candidates for leadership roles. timing is important, but more important is to spot the red flags in the hiring process.

- Most start-ups begin by being very homogeneous in terms of thought process. founders and early-stage employees almost always have something strong in common that brings them together. This homogeneity is helpful in acting with speed in the early stages of growth, but need not necessarily be an asset at a later stage. It actually pays to build diversity into the teams as the start-up begins to scale.

- At rapidly scaling start-ups, some people start capping out in terms of capabilities and are not able to keep pace with the growing demands. So, when symptoms of things beginning to break begin to show up, it is critical to step back a bit and figure out whether the team needs to be strengthened or whether the leader needs to be replaced.

- Another important decision is whether generalists would work better or specialists would work better at different points of time for different functions.

- Learning and development is the cornerstone of creating leadership capacity, but start-ups are always brimming with intense activity and people cannot easily be pulled out of jobs to undergo leadership development. Separating learning from work rarely works, and hence it is important to integrate learning into work.

- Creating a culture of high performance, dealing with non-performers, coaching and designing the right feedback mechanisms are absolutely crucial for scaling.

There are standard frameworks that could be leveraged to strengthen these programmes.

**