‘If you want your children to be intelligent, read fairy tales to them.’

—Albert Einstein

You can’t have a happy family unless you’re happy yourself. Raageshwari Loomba, an award-winning speaker on mindfulness, shows us how to create an excellent atmosphere for the entire family to thrive in. Her new book, Building a Happy Family brings to you 11 simple mindfulness philosophies that will enrich and strengthen your and your children’s inner world.

Through scientific research and her own intimate story of heartbreak and facial paralysis, Raageshwari emphasises how our thoughts can manifest further struggles or glory, and how teaching children early that our inner world attracts our outer world is key.

In this excerpt from her new book, Raageshwari tells you about the benefits of reading, and how to get your children to become readers!

Imagination will save the day

Einstein said, ‘Imagination is everything.’ It can relieve a child of stress or anxiety and have creative benefits for you as well. It’s the only pathway for us to escape into a magical world, especially when things are not going our way. If your boss is acting boorish, or you’re stuck in a traffic jam or have a dentist’s appointment coming up, you have to shift focus to something joyful and uplifting.

Imagination truly thrives with the guidance of books. No wonder research in 2016 by Harvard Health Publishing (Harvard Medical School) says that ‘reading books could add years to your life’. I definitely think it has to do with them being happier as they have more imagination.

‘The researchers studied the records of 5635 participants in the health and retirement study, an ongoing investigation of people who were fifty or older had provided information on their reading habits when the study began. They determined that people who read books regularly had a 20 per cent lower risk of dying over the next twelve years compared with people who weren’t readers or who read periodicals. This difference remained regardless of race, education, state of health, wealth, marital status and depression.’

Now, children need imagination to believe that anything is achievable and possible, especially during their most formative years when they build beliefs and patterns for life.

Reading books to children helps boost their brain power, as opposed to the TV or phone, which offers comatose viewing that actually stills the brain.

Reading to children introduces them to emotions that we display as we read out to them. As a result, your child will have a larger vocabulary, greater confidence and wonderful social skills.

Perhaps you already know all this, but did you know that YOU are the greatest conduit through which your child will learn to love books?

Sudhanshu and I read to Samaya every evening even when she was in my womb. We decided to watch TV only by appointment over the weekends and view shows that were musical or uplifting. We knew that if we wished to inculcate reading habits in our child, we would have to first do away with mindless browsing of the Internet or the TV.

We bought fairy-tale books that we had loved as children. We loved reading them to Samaya. It opened so many windows into our own childhood and interesting memories came flooding back. I cannot recommend this practice enough. You will bond as a couple on deeper levels.

Plant the seeds of reading

When Samaya was born, we read picture pop-up books to her every evening. Sometimes she would cry, sometimes babble, sometimes just go to sleep, but we were consistent and never ended a reading session without finishing a book. Soon she started to nibble on the books, and then she started to tear them and destroy them. We accepted this interaction. It was a relationship with books, and we had to be patient and be positive that it would grow into a lifelong bond. As she grew up, she crawled around distracted, while we kept reading to her after supper every evening. It did seem she was least interested, but we knew she was absorbing it all like a sponge. Samaya would look at covers and jabber away, trying to say the names.

At fifteen months old, she pulled out a book from her library and came running to us, prattling, ‘Story book.’ She was hooked to one of the purest forms of entertainment, the most loyal friend one can have, and a world of its own: books!

At age two, she knew her choices and intricate titles such as Incredible You, Snail and the Whale and Giraffes Can’t Dance. She is now three, and her mornings begin with a book and her evenings end with a book. She uses words such as kaleidoscope, stabilizer, Stegosaurus, Panchatantra and meditation. She is forming an understanding of good and bad, why empathy is important, why reaching out to strangers can be a good thing too.

Reading for pleasure

I know of many adults who read long and information- packed documents all day at the office. Hence, they don’t wish to read a word when they come back home, let alone read to children. I understand as I’m married to a barrister. However, reading for pleasure is completely different, and there is enough research to back this. Scientists have urged professionals to not mix ‘reading information’ with ‘reading for pleasure’.1 Evidence suggests that no matter how stressed and worn out you may be, once you read for pleasure, you immediately feel re-energized as this is a mindful activity of stepping into another world.

Adults argue with me, saying that TV is a greater escape as they just have to sit on a couch with food and enjoy a show. I don’t disregard TV, as with selective viewing we can gain immense insights and knowledge. However, if you are seeking mindfulness, peace and energy in your life, books are a far greater escape.

TV and films may also bring new worlds into our lives with vibrant characters. They can push us to the edge of our seats and entertain, but books are inclusive. With books, it becomes about your story, your character and your life. This movement in the brain leads to imagination that is vital in our world today.

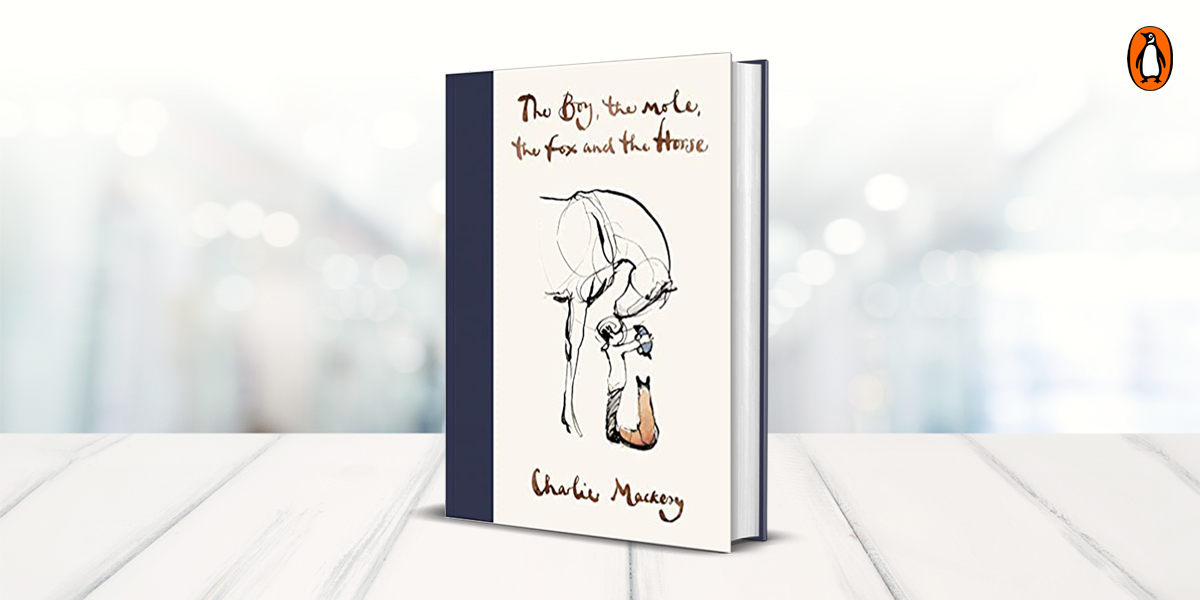

Reading for pleasure entails picking up a book that has no connection with your work. So it could be a book on travel, science fiction, a biography or just a cookbook. It is reading a book with no agenda and no schema, for relaxation and the joy it brings you.

Interestingly, for toddlers, every book is a pathway to pleasure.

Reading parents will have reading children

I have learnt that discipline and diktats rarely work in the long run. They have not worked on us and will not work on our children, especially if you want confident children with free spirits and buzzing minds. What works is setting examples. BE what you wish to see. We cannot expect our children to pick up books if we are busy picking up phones. Your children look up to you more than you know. Hence, they love aping you. So grab a book and get started. Remain focused and give books your complete commitment first, and the rest will follow.

In case the well-being of the family is not incentive enough, the beauty about the glorious habit of reading is that you will finally start to connect with your core and the real you. People spend a lifetime being lost, without knowing themselves. With books, you will gift this pathway to self- realization to your child and yourself.

You may frown upon my selling reading to you when your concern is your children. Well, children do not do as they are told but as they see. Research tells us that children who become avid readers live in an environment where family members read at home. Parents who are members of libraries, read books and read aloud to their children are twice as likely to have children who are voracious readers. Also, you must be aware by now that this book emphasizes the philosophy that mindful parenting is about bringing up the parent and not the child. The focus has to be on us, our inner world, be it when we are dealing with children, spouses or our colleagues at work. Once you master this art, you will thrive.

In Building a Happy Family, parents are taught to encourage their children’s original expressions, creativity and joy, and not lose sight of it in their own lives too. This is the secret to a happy family!