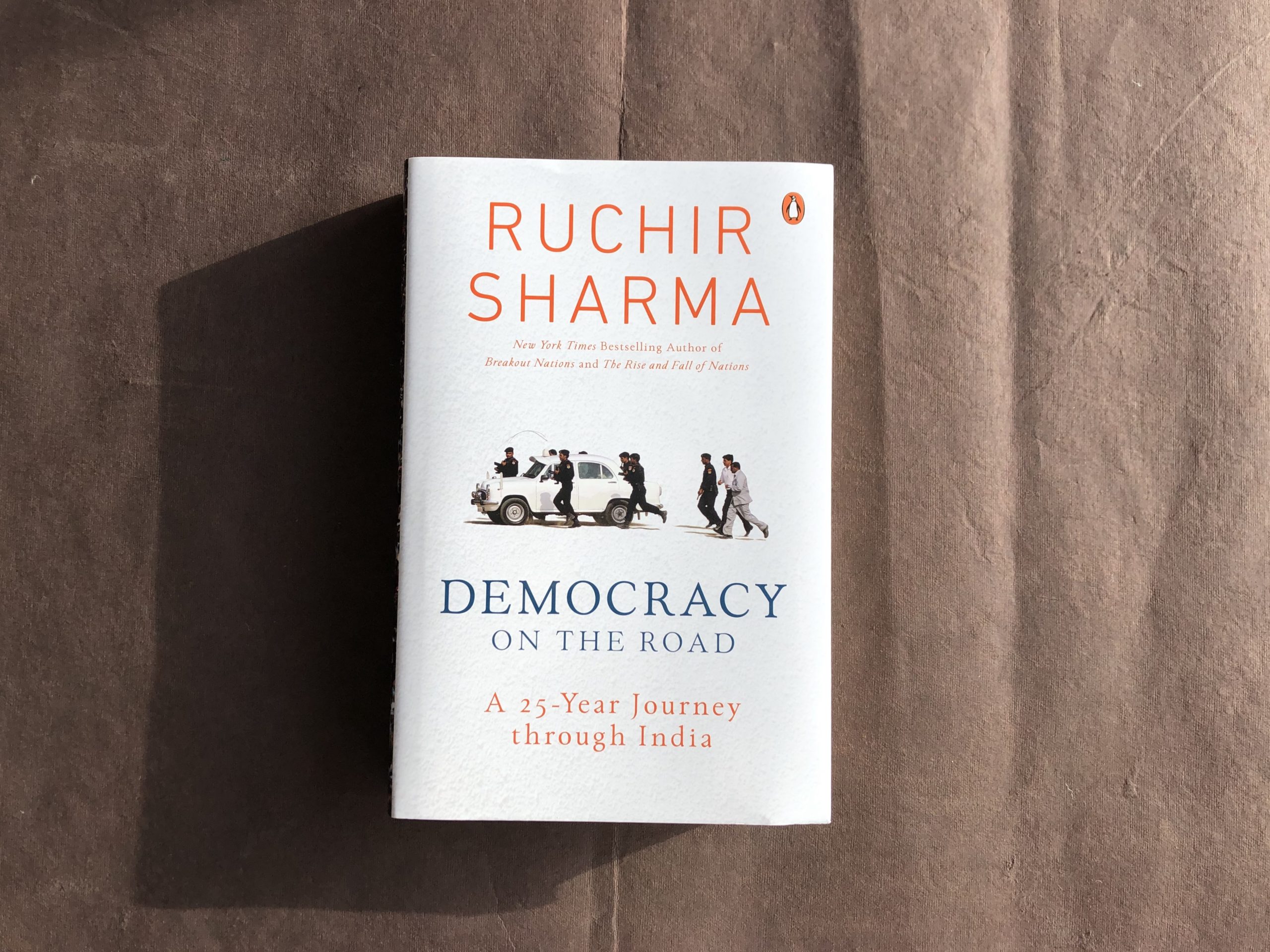

On the eve of a landmark general election, Ruchir Sharma offers an unrivalled portrait of how India and its democracy work, drawn from his two decades on the road chasing election campaigns across every major state, travelling the equivalent of a lap around the earth.

Here is an excerpt from Ruchir Sharma’s book, Democracy on the Road that talks about the power packed campaign led by Mamata Banerjee in May 2011.

Leading the opposition charge was Mamata Banerjee, a Bengali Brahmin who split from the Congress to form her own party in 1998 and had been railing against Marxist ‘tyranny’ for years, mostly to no avail. The Tata conflict, and a second deadly government attempt to acquire agricultural land in and around Nandigram in the district of Purba Medinipur, had given Mamata’s campaign against Marxist rule new momentum and credibility.

We saw Mamata for the first time at a rally in Kolkata, where she sprang out of the helicopter and race-walked past party supporters, a big boss in a diminutive frame, dressed austerely in a white sari with a blue border. Her bearing broadcast immediately that she had no time for the usual campaign greetings; she was a one-woman dynamo running a lifelong crusade, eager to topple communism yesterday.

A poet herself, Mamata promised not only to restore English instruction but also to bring back the poetry of Bengal greats such as Rabindranath Tagore and Kazi Nazrul Islam, and the stories of Bengal heroes like ‘Binoy, Badal and Dinesh’, which the Marxists had expunged as too bourgeois, and replaced with party-approved literature. While English is an aspirational language all over India, perhaps only in Bengal could a politician campaign on promises to restore local poetry to the school curriculum.

She promised that under her All India Trinamool Congress (TMC)—the ‘party of the marginalized’—things would be different. Bengal would have modern schools, colleges and health clinics, with no proof of party loyalty required for access. Non-party members would no longer have to travel out of state for medical treatment. Her campaign slogan promised ‘poriborton’, the Bengali spin on ‘parivartan’ or change. As interesting as what Mamata said was what she didn’t say. Neither the Congress nor the BJP had cracked 7 per cent of the vote in recent Bengal elections, and they hardly bore mention in Mamata’s speech. The caste and religious undercurrents that drive much of Indian politics barely surfaced either, since Bengal was divided mainly between Marxist party members and everyone else. Tapping popular frustration with thirty-four years of Marxist rule, Mamata’s party won in resounding fashion, taking 184 of the 294 state assembly seats, and she became the new chief minister. The Marxists finished a distant second….

Economic growth had picked up at least moderately since the communists departed. Infant mortality was falling. Construction was booming all over the capital, spilling into the outskirts. Amit Mitra, state finance minister under Mamata, told us investment was flowing into cement and fertilizer plants, small- and medium-size companies were growing rapidly and that Tata had begun to expand again in the state.

When Mamata came to power in 2011, she had fired police officials who did not toe her party line, and harassed critics who posted mocking cartoons of her on social media. She was seen as erratic, volatile, an autocrat who brooked no challenge within her own party. Mamata’s writ still ran large, but she was settling down and opening up, as the Marxists fell into disarray. During the last campaign, Mamata had refused to meet us because some of our companions had ties to leading Marxists in Delhi, but this time she called them up to the stage before a Kolkata rally and greeted them warmly.

As Mamata went on the offensive there were flashes of the old paranoia, and over the course of the campaign she would attack everyone from Modi and the media to the Election Commission and the security apparatus for conspiring against her. Her crowds lapped it up. As soon as her Kolkata rally ended and Mamata made it past her security cordon, she was mobbed by supporters, young and old, who wanted to kiss her hand, touch her feet, or receive her blessings.

Over this five-week campaign, Mamata would claim to walk 1000 kilometres in the sweltering heat of April and May to address more than 160 meetings, and while the numbers were implausible, her energy and her centrality to the TMC were not in question. The joke in Kolkata was that ‘there is only one post in the TMC and Mamata holds it. Everyone else is a lamppost.’ She was running a highly centralized government in which her word was the only one that really mattered, yet she was delivering enough to ordinary people to win them over. Many said Mamata had executed on her promises to improve roads and electricity. She had offered subsidies to bring down the price of wheat, vegetables and rice, which were selling for a few rupees per kilo. She had also given free bicycles to girls as an incentive and means to get to school, and offered wedding subsidies to young women.

In the end the TMC won easily. After five straight terms under Marxist party leaders, Bengal may simply not have been ready to throw out Mamata after one. Her personal charisma prevailed over the imploding Marxists and their opportunistic alliance with the Congress. She had mellowed, growing open enough to industry to win business support, remaining generous enough with the public purse to win votes from the poor.

Mamata was also riding the growing wave of voter support for single leaders, whose unmarried status seemed to confirm their claims of all-in devotion to public service. Among India’s twenty one most populous states, there were no unmarried chief ministers in 1988, but by 2016 there were seven, including Mamata, seemingly lifted by growing voter distaste for nepotism inside political parties, and the corruption that flows naturally from running parties as a family business. Mamata had in fact remained far more ascetic in her personal tastes than many other supremos. Even as chief minister she lived in her small ancestral home in the Kolkata neighbourhood of Kalighat. Passing by the home we were stunned to see it in a state of decay with a dilapidated grey tiled roof and rotting bamboo shafts—a stark contrast to the sandstone palaces Mayawati had built for herself in UP. Mamata’s image as a single leader with no taste for diamonds had made her largely impervious to the corruption charges that so often topple Indian governments, and helped her secure this second term.

Democracy on the Road takes readers on a rollicking ride with Ruchir and his merry band of fellow writers as they talk to farmers, shopkeepers and CEOs from Rajasthan to Tamil Nadu, and interview leaders from Narendra Modi to Rahul Gandhi.