The river Ganga enjoys a special place in the hearts of millions. In Ganga: The Many Pasts of a River, historian Sudipta Sen tells the fascinating story of the world’s third-largest river from prehistoric times to the present.

Here is an excerpt from the first chapter titled The World of Pilgrims

Of the many odes written to the Ganga in various Indian languages, these lines are perhaps the most poignant:

O River, daughter of Sage Janhu, you redeem the virtuous

But they are redeemed by their own good deeds—

where’s your marvel there?

If you can give me salvation—I, a hopeless sinner—then I would say

That is your greatness, your true greatness

Those who have been abandoned by their own mothers,

Those that friends and relatives will not even touch

Those whose very sight makes a passerby gasp and take the name of the Lord

You take such living dead in your own arms

O Bhagirathi, you are the most compassionate mother of all

These Sanskrit s´lokas, taken from an eight-stanza ode to the Ganga, have been a part of the oral tradition in Bengal for centuries, and many people knew them by heart just a generation ago. They were composed—surprisingly—not by a Brahmin, not even by a Hindu, but by a thirteenth-century author who went by the popular name of Darap Khan Gaji. The noted Bengali linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterji identified “‘Darap Khan’” as Zafar Khan Ghazi, who is credited with daring military exploits during the first major phase of Islamic expansion in Bengal toward the end of the thirteenth century, after the Turkish Sultanate had been established in northern India around Delhi as the new capital. To find what remains of the memory of Zafar Khan, a self-proclaimed virtuous warrior of Islam in Bengal, you have to travel to Tribeni, a small town in Hugli in West Bengal on the banks of the Bhagirathi, which is the name of the Ganga there. This place, which was considered very sacred in antiquity, is where the Ganga once branched off into three streams: the Saraswati River flowed southwest beyond the port of Saptagram, the Jamuna River2 flowed southeast, and the Bhagirathi proper flowed through the present Hugli channel all the way to the location where English traders much later erected a city, Calcutta.

Zafar Khan Ghazi was said to have struck terror among the local Hindus, attacking their temples and idols during the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. He conquered the pilgrimage of Tribeni and the port of Saptagram, destroyed a large and ancient temple there, and allegedly used the spoils to build an imposing mosque. He took the title of Ghazi, warrior of Islam, and established a school for Arabic learning and a charity (dar-ulkhairat). One of the oldest Bengali Shia texts has a curious tribute to the Ghazi:

On the quays of Tribeni pay respect to Daraf Khan

Whose water for wazu [ritual ablutions] came from the River Ganga

The little we can surmise about Zafar Khan’s life and death reminds us that the sacredness and the value of a river and the landscape that it flows through are entwined with the practice of everyday life. He seemed to have realized this later in life. He became a friend of the poor, donned the robes of a Sufi mystic, learned to write beautiful Sanskrit, and eventually won the hearts of the local people he had tried to convert forcibly to Islam in his youth. For generations to come, Zafar Khan became an emblem of the composite culture of Hindus and Muslims in Bengal, which shared a sense of enchantment with the landscape of the delta. The noted Bengali critic, novelist, and historian Bhudev Mukhopadhyay, writing in the latter half of the nineteenth century in his utopian history of India, imagined a country where people of all faiths paid obeisance to the river by singing the hymns of Darap Khan.4 Mirza Ghalib, the foremost Urdu poet of his time, echoed a similar sentiment when he visited Varanasi (Banaras) in the early spring of 1828 and fell in love with the city, composing a poem in Persian called “Chiragh-e-Dair” [The Lamp of the Temple], a memorable tribute in which he named the city the “Kaba of Hindustan”:

May Heaven keep

The Grandeur of Banaras,

Arbour of bliss, meadow of joy,

For oft-returning souls

Their journey’s end.

He almost wished that he could have left his own religion to pass his life on the bank of the Ganga with prayer beads, a sacred thread, and a mark on his forehead.

One of the oldest explanations for this abiding faith in the purity of the waters of the Ganga has to do with the practice of pilgrimage that has for centuries provided a stage on which to reenact the difficult inner journey

of reconciliation and atonement, often imagined through the pristine Himalayan landscape of mountains and glacial melts—a terrain that the great Sanskrit poet Kalidasa describes as “dis´ı¯ devata¯tma¯” [the country of divine beings]. Ritual baths and offerings at sacred spots along the river are tied to this sense of geography, which is steeped in ideas and images drawn from history, myth, and nature as shared forms of reckoning, an experience (tı¯rthabha¯va) difficult to capture in words. When Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, traveled in search of wisdom on the Hindu pilgrimages of the east, as recorded in the Janam Sakhi, it was not the usual places of ritual obeisance that impressed him. He was entranced instead by a flock of migratory swans alighting nearby. They appeared much closer to heaven than did the throngs of pious Hindus. With their shining silver-white plumage and burnished eyes, the swans were messengers who flew across the Himalayas, from India to Central Asia and back, year after year.8 It is the journey, the story conveys, and not the destination, that defines the purpose of pilgrimage. Such convictions and practices, along with other aspects of Hindu practice, have been misunderstood by an array of observers and critics from the West, including missionaries, colonial administrators, authors, and travel writers.

Seamlessly weaving together geography, ecology and religious history, Ganga: The Many Pasts of a River paints a remarkable portrait of India’s most sacred and beloved river.

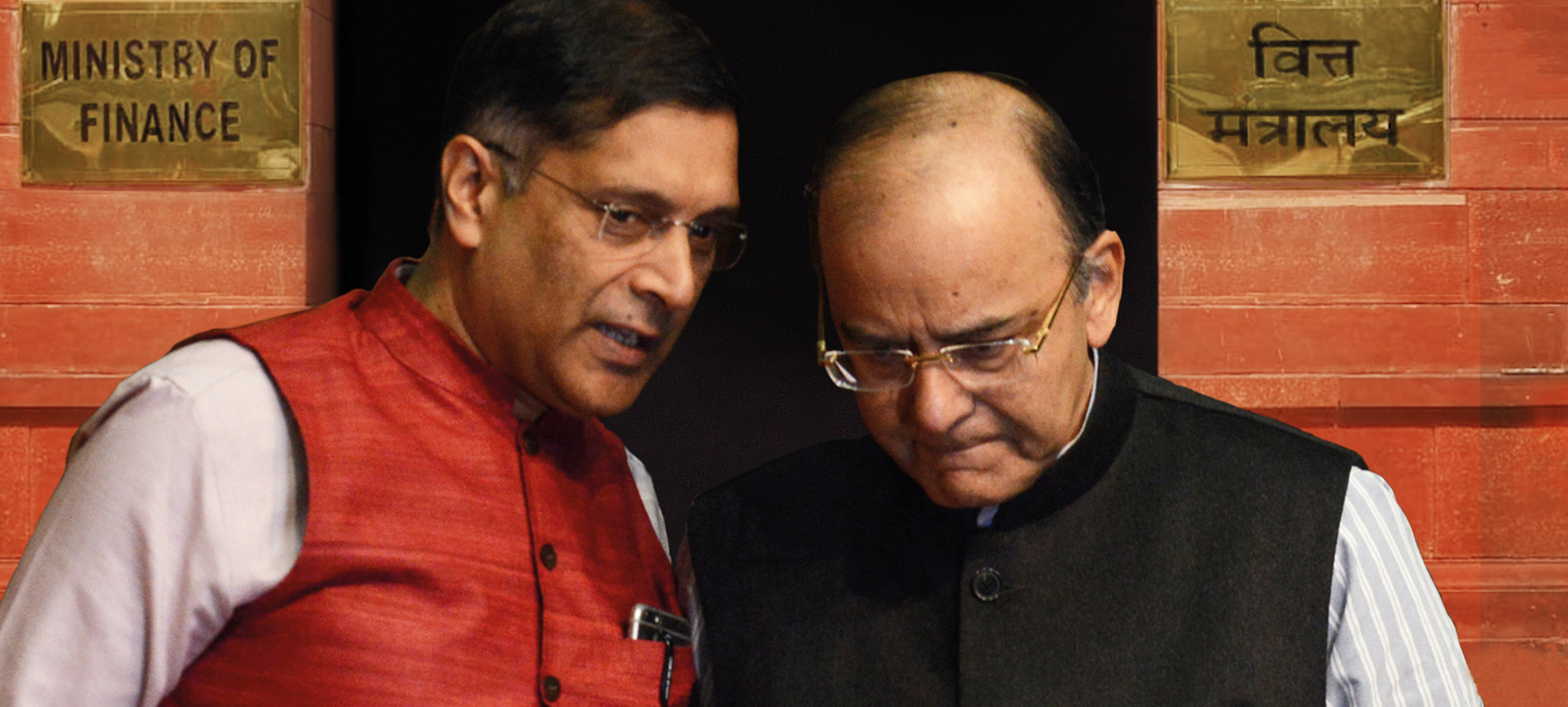

Recognized as one of the Top 100 Global Thinkers according to Foreign Policy magazine, Arvind Subramanian’s

Recognized as one of the Top 100 Global Thinkers according to Foreign Policy magazine, Arvind Subramanian’s