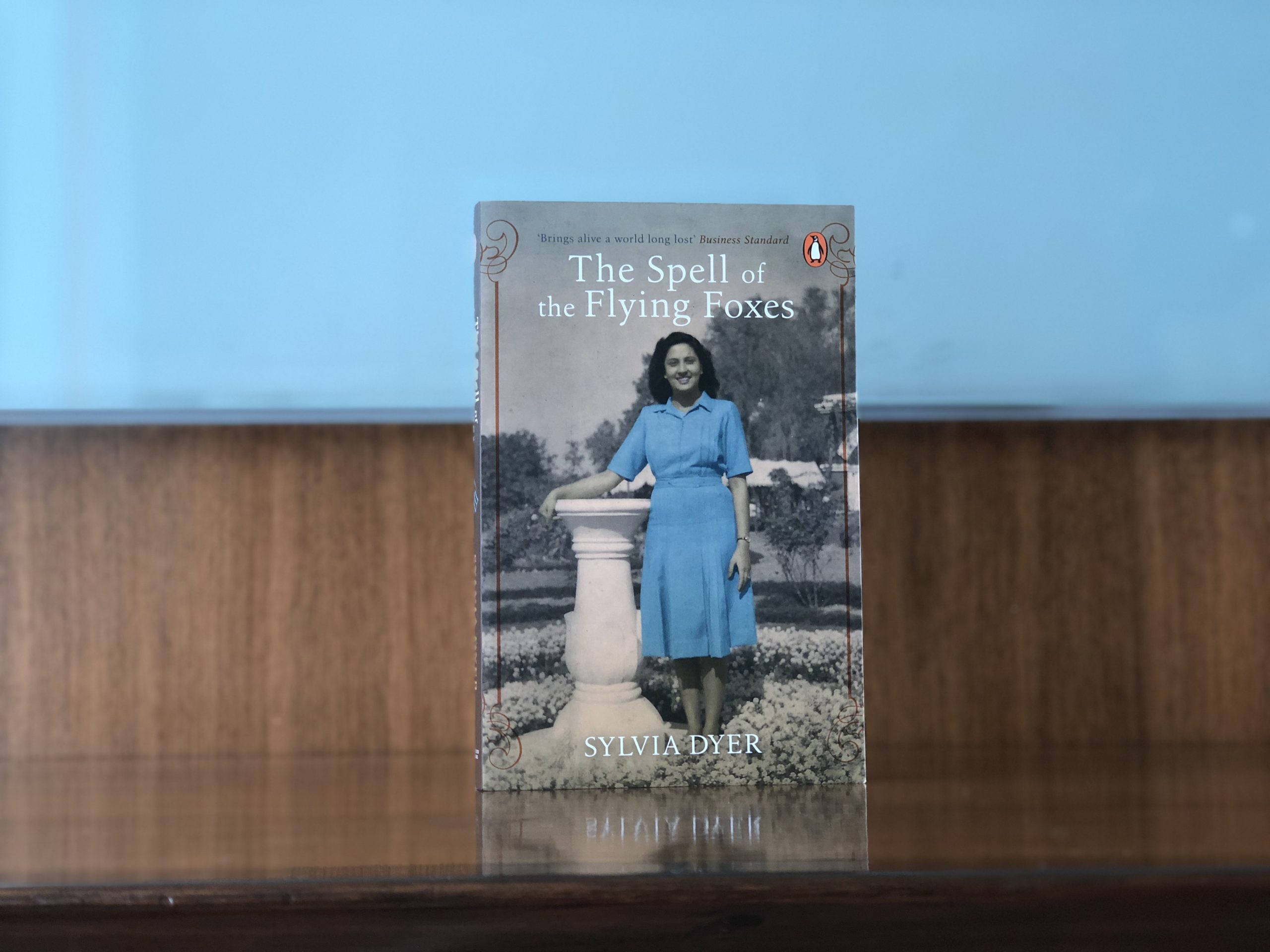

It is a commonly held belief in India that flying foxes augur prosperity. They were certainly abundant in the Champaran region of north Bihar. Here in 1845, an Englishman, Alfred Augustus Tripe, fascinated by the prospect of farming indigo, known as Blue Gold, was drawn to its isolated wilderness.

In The Spell of the Flying Foxes author Sylvia Dyer, recaptures what now seems a fairy-tale world of picturesque beauty, peopled by unique and unforgettable characters.

————————————————————

Here is an excerpt from the chapter Something Strange and Sinister.

The floods that year were devastating. But now it was all over. With the coming of September the water receded. The transplanted paddy seedlings stood vivid green and upright, and the sugar cane was six feet high, with still another three months to go. All should have been well with our world.

But it was not.

The pi-dogs of Musahari Tola were seized by a sudden jitteriness, insisting on being let into the huts to sleep with the Musahars at night. They were kicked out with rough reprimands: ‘Worthless pariahs, are you watchdogs or lapdogs?’

Early next morning, one of the watchdogs had quit and was never seen again. Slowly more watchdogs began to disappear, and always one at a time. It was a mystery in a land where mysteries were quickly cleared up.

Other villages too were in for mysterious disappearances, villages where only the upper-caste Hindus lived. Most of them owned at least one acre of this fertile land and were comfortably off. Their wives lived in purdah, seldom stepping out to work or socialize, but spending their lives as honoured housewives in their own thatched prisons, for each home had a little private courtyard with high thatched walls. Inside they ground the grain, milked the buffalo, cooked the meals and lived out their lives in cloistered contentment. In the dark hours just before dawn, proud sons of the village mounted on their buffaloes made a slow but certain beeline for our mango groves, or the adjacent fi elds, to graze furtively on the current crops, returning at sunrise, the riders full of song and the buffaloes full of milk for their owners.

But one morning, a buffalo failed to return.

‘I tell you, brother, it has been sent to the pound!’

‘The pound? But then, where is the boy? Has the earth swallowed him up?’

That evening we went to visit Harry. He had built a narrow bamboo bridge across the Mahari so he could visit us or take a short cut through Puchkurwa to the railway station. It served its purpose well enough till a bad fl ood, like the one we had just experienced, swept it clean away.

So we sat on our bank, and he on his, with sixty feet of water in between. It was a little more than knee-deep in most places, scarcely a setback for our usual social exchanges. His servants waded across with chairs for us, and we sat shouting at each other, above the ripple of restless, running water.

Ghogra appeared on Harry’s side, in a snow-white uniform, dhoti hitched up, and a tray of fried snacks carried high above his head as he waded into the water. He had almost reached our bank when, all of a sudden, he lost his footing. His turban flew like a snowball. The eyes in the bulldog face popped, and the mouth opened. And he was gone.

A moment later he reappeared coated with grey silt, and still clutching the tray. But the fried snacks had gone to the fishes, along with the dishes. Even from our bank, we could see the irritation on Harry’s face. They were from his best set. ‘He is the king of idiots, this Ghogra, and such a show-off!’

Nobody laughed out loud.

The setting sun sent out a blaze of fiery orange from the western horizon as Ghogra was making his slimy way back to Harry’s bank, grumbling about the upkeep of bridges, when—

‘Shh!’ Dad raised a hand for silence. ‘Crikey! Did you hear that?’

‘Hear what?’

‘A call . . . I could swear I heard a strange call in the distance, bloody strange.’

Some of the servants had heard it too. ‘Baap re baap! It’s a bhooth—an evil spirit!’