In Bulbul Sharma’s new book, Murder at the Happy Home for the Aged, the tranquillity at the Happy Home is shattered when a body is found hanging in the garden. The inhabitants of the home are first perplexed, then decide to come together to solve the murder that has suddenly brought the violence of the world into their Goan arcadia.

Set in the lush landscape of Goa, where tourists flock from all over the world, where the rich set come to play, bringing in their wake fortune-hunters and other predators, the cast of possible murderers is infinite. But patiently, and with flashes of inspiration, the unlikely detectives follow the clues and in doing so emerge from the isolated and separate worlds they had inhabited for so long.

Here are some snippets from the book that you’re bound to enjoy!

Category: Excerpts

Fuzzies vs Techies in the World of Innovation

Scott Hartley first heard the terms ‘fuzzy’ and ‘techie’ while studying political science at Stanford University. If you had majored in the humanities or social sciences, you were a fuzzy. If you had majored in the computer sciences, you were a techie. This informal division quietly found its way into a default assumption that has misled the business world for decades-that it’s the techies who drive innovation.

In his book, The Fuzzy and the Techie, Hartley looks inside some of the world’s most dynamic new companies, reveals breakthrough fuzzy-techie collaborations, and explores how such associations are at the centre of innovation in business, education and government, and why liberal arts are still relevant in our techie world.

Here is an excerpt.

————————————————————————————————————————————————

The terms ‘fuzzy’ and ‘techie’ are used to respectively describe those students of the humanities and social sciences, and those students of the engineering or hard sciences at Stanford University. Stanford is what’s known as a ‘liberal arts’ university not because it focuses on subjects that are necessarily liberal, or artistic, but because each student is required to study a broad set of subjects prior to specialization. The term liberal arts comes from the Latin, artes liberales, and denotes disciplines such as music, geometry, and philosophy that can together stretch the mind in different directions and, in that process, make it free. Each of these subjects is meant to broaden the student, force them to think critically, to debate, and to grapple with ambiguities inherent in subjects like philosophy. They are also meant to help the student cultivate empathy for others in subjects such as literature, which forces one to view the world through the eyes of another human being. In short, they are less focused on specific job preparation than they are about the cultivation of a well-rounded human being. But at Stanford, beneath these light-hearted appellations of ‘fuzzies’ and ‘techies’ also rest some charged opinions on degree equality, vocational application, and the role of education. Not surprisingly, these are opinions that have bubbled well beyond the vast acreage of Stanford’s palm-fringed quads and golden hillsides, into Silicon Valley. In fact, these questions of degree equality, automation and relevant skill sets in tomorrow’s technologyled economy are ones we face in India and across the world.

This decades-old debate to separate liberal arts majors from the students who write code and develop software has come to represent a modern incarnation of physicist and novelist Charles Perry Snow’s Two Cultures a false dichotomy between those who are versed in the classical liberal arts, and those with the requisite vocational skills to succeed in tomorrow’s technology-led economy. In India, from the earliest entrance exam standards that determine whether or not students move toward or away from engineering, we have created policy and education pathways that separate rather than foster an understanding between these ‘two cultures.’ Whether a student sits for the Joint Entrance Exam (JEE) for admission to an Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), for the Birla Institute of Technology and Science Admission Test (BITSAT), the VIT Engineering Entrance Exam for a coveted engineering seat at Vellore Institute of Technology or for a regional common entrance exam in Maharashtra, Karnataka, or West Bengal, students are quickly funneled down very specific predetermined paths, and are perhaps less able to explore their own passions or values. And this is not specific or unique to India, but endemic across many cultures and societies.

This book not only seeks to reframe this ongoing debate, by taking into account the very real need for science, technology, engineering and math, so-called ‘STEM’ majors, but also acknowledges their faux opposition to the liberal arts. Indeed, as we evolve our technology to make it ever more accessible and democratic, and as it becomes ever more ubiquitous, the timeless questions of the liberal arts have become essential requirements of our new technological instruments. While those fabled graduates of the Indian Institutes of Technology, or of the great engineering academies such as Manipal, develop critical skills and retain steadfast importance in laying the technological infrastructure, most successful start-ups require great industry context, psychology in understanding user needs and wants, intuitive design, and adept communication and collaboration skills. These are the very skill sets our graduates in literature, philosophy, and the social sciences provide. These are not separate or add-on skills, but the imperative components alongside any technological literacy.

As a fuzzy having grown up in a techie world, this false dichotomy has been something I observed in Palo Alto, California, where Steve Jobs donated the Apple computers we used in high school. This was something I observed furthermore as a Stanford student; as an employee of Google, where I spent over a year launching two teams in Hyderabad and Gurugram, India, as an employee of Facebook, and then as a venture capitalist at a $2-billion fund on Sand Hill Road, California. Peering behind the veil of our greatest technology, it is often our greatest humanity that makes it whole. Having met with thousands of companies, the story I want to share with India is that no matter what you’ve studied, there is a very real, and a very relevant, role for you to play in tomorrow’s tech economy. Our technology ought to provide us with great hope rather than fear, and we require policymakers, educators, parents and students to recognize this false divide between becoming technically literate, and building on our most important skills as humans.

Our greatest human problems require that we blend an appreciation for technology with a continued respect for those who study the human conditions, for they are the ones who teach us how to apply our technology, and to what ends it must actually be purposed. We ought to consider the true value of the liberal arts as we continue to embrace and pioneer our new technological tools. As we move forward, we require the timeless and the timely, the great poets and literature of Bengal and the glass-towers of Bengaluru.

The President is Missing! – An Excerpt

“The President is missing. The world is in shock.”

James Patterson and former-president Bill Clinton’s new book, The President is Missing confronts a threat so huge that it jeopardizes not just Pennsylvania Avenue and Wall Street, but all of America. Uncertainty and fear grip the nation.

Set over the course of three days, The President Is Missing sheds a stunning light upon the inner workings and vulnerabilities of the United States. It is filled with information that only a former Commander-in-Chief could know.

Here is an excerpt from the book.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Everything I did was to protect my country. I’d do it again. The problem is, I can’t say any of that.

“All I can tell you is that I have always acted with the security of my country in mind. And I always will.”

I see Carolyn in the corner, reading something on her phone, responding. I maintain eye contact in case I need to drop everything and act on it. Something from General Burke at CENTCOM? From the under secretary of defense? From the Imminent Threat Response Team? We have a lot of balls in the air right now, trying to monitor and defend against this threat. The other shoe could drop at any minute. We think—we hope—that we have another day, at least. But the only thing that is certain is that nothing is certain. We have to be ready any minute, right now, in case—

“Is calling the leaders of ISIS protecting our country?”

“What? I say, returning my focus to this hearing. “What are you talking about? I’ve never called the leaders of ISIS. What does ISIS have to do with this?”

Before I’ve completed my answer, I realize what I’ve done. I wish I could reach out and grab the words and stuff them back in my mouth. But it’s too late. He caught me when I was looking the other way.

“Oh,” he says, “so when I ask you whether you’ve called the leaders of ISIS, you say no, unequivocally. But when the Speaker asks you whether you’ve called Suliman Cindoruk, your answer is ‘executive privilege.’ I think the American people can understand the difference.”

I blow out air and look over at Carolyn Brock, who maintains that implacable expression, though I can imagine a hint of I-told-ya-so in her narrowed eyes.

“Congressman Kearns, this is a matter of national security. It’s not a game of gotcha. This is serious business. Whenever you’re ready to ask a serious question, I’ll be happy to answer.”

“An American died in that fight in Algeria, Mr. President. An American, A CIA operative named Nathan Cromartie, died stopping that anti-Russia militia group from killing Suliman Cindoruk. I think the American people consider that to be serious.”

“Nathan Cromartie was a hero,” I say. “We mourn his loss. I mourn his loss.”

“You’ve heard his mother speak out on this,” he says.

I have. We all have. After what happened in Algeria, we disclosed nothing publicly. We couldn’t. But then the militia group published video of a dead American online, and it didn’t take long before Clara Cromartie identified him as her son, Nathan. She outed him as a CIA operative, too. It was one gigantic shitstorm. The media rushed to her, and within hours she was demanding to know why her son had to die to protect a terrorist responsible for the deaths of hundreds of innocent people, including many Americans. In her grief and pain, she practically wrote the script for the select committee hearing.

“Don’t you think you owe the Cromartie family answers, Mr. President?”

“Nathan Cromartie was a hero,” I say again. “He was a patriot. And he understood as well as anyone that much of what we do in the interest of national security cannot be discussed publicly. I’ve spoken privately to Mrs. Cromartie, and I’m deeply sorry for what happened to her son. Beyond that, I won’t comment. I can’t, and I won’t.”

“Well, in hindsight, Mr. President,” he says, “do you think maybe your policy of negotiating with terrorists hasn’t worked out so well?”

“I don’t negotiate with terrorists.”

“Whatever you want to call it,” he says. “Calling them. Hashing things out with them. Coddling them—“

“I don’t coddle—“

The lights flicker overhead, two quick blinks of interruption. Some groans in response, and Carolyn Brock perks up, writing herself a mental note.

He uses the pause to jump in for another question.

“You’ve made no secret, Mr. President, that you prefer dialogue over shows of force, that you’d rather talk things out with terrorists.”

“No,” I say, drawing out the word, my pulse throbbing in my temple, because that kind of oversimplification epitomizes everything that’s wrong with our politics, “what I have said repeatedly is that if there is a way to peacefully resolve a situation, the peaceful way is the better way. Engaging is not surrendering. Are we here to have a foreign police debate, Congressman? I’d hate to interrupt this witch hunt with a substantive conversation.”

I glance over to the corner of the room, where Carolyn Brock winces, a rare break in her implacable expression.

“Engaging the enemy is one way to put it, Mr. President. Coddling is another way.”

“I do not coddle our enemies,” I say. “Nor do I renounce the use of force in dealing with them. Force is always an option, but I will not use it unless I deem it necessary. That might be hard to understand for some country club, trust-fund baby, who spent his life chugging beer bongs and paddling pledges in some secret-skull college fraternity and calling everybody by their initials, but I have met the enemy head-on in a battlefield. I will pause before I send our sons and daughters into battle, because I was one of those sons, and I know the risks.”

Jenny is leaning forward, wanting more, always wanting me to expound on the details of my military service. Tell them about your tour of duty. Tell them about your time as a POW. Tell them about your injuries, the torture. It was an endless struggle during the campaign, one of the things about me that tested the most favorably. If my advisers had their way, it would have been just about the only thing I ever discussed. But I never gave in. Some things you just don’t talk about.

“Are you finished, Mr. Pres—“

“No, I’m not finished. I already explained all of this to House leadership, to the Speaker and others. I told you I couldn’t have this hearing. You could have said, ‘Okay, Mr. President, we are patriots, too, and we will respect what you’re doing, even if you can’t tell us everything that’s going on.’ But you didn’t do that, did you? You couldn’t resist the chance to haul me in and score points. So let me say to you publicly what I said to you privately. I will not answer your specific questions about conversations I’ve had or actions I’ve taken, because they are dangerous. They are a threat to our national security. If I have to lose this office to protect this country, I will do it. But make no mistake. I have never taken a single action, or uttered a single word, without the safety and security of the United States foremost in my mind. And I never will.”

My questioner is not the least bit deterred by the insults I’ve hurled. He is undoubtedly encouraged by the fact that his questions have now firmly found their place under my skin. He is looking at his notes again, at his flow chart of questions and follow-ups, while I try to calm myself.

“What’s the toughest decision you’ve make this week, Mr. Kearns? Which bow tie to wear to the hearing? Which side to part your hair for that ridiculous combover that isn’t fooling anybody?

“Lately, I spend almost all my time trying to keep this country safe. That requires tough decisions. Sometimes those decisions have to be made when there are many unknowns. Sometimes all the options are flat-out shitty, and I have to choose the least flat-out shitty one. Of course, I wonder if I’ve made the right call, and whether it will work out in the end. So I just do the best I can. And live with it.

“That means I also have to live with the criticism, even when it comes form an opportunistic political hack picking out one move on the chess board without knowing what the rest of the game looks like, then turning that move inside-out without having a single clue how much he might be endangering our nation.

“Mr. Kearns, I’d like to discuss all my actions with you, but there are national security considerations that just don’t permit it. I know you know that, of course. But I also know it’s hard to pass up an easy cheap shot.”

In the corner, Danny Ackers has his hands up, signaling for a time-out.

“Yeah, you know what? You’re right, Danny. It’s time. I’m done with this. This is over. We’re done.”

I lash out and whack the microphone off the table. I knock over my chair as I get to my feet.

Extracted from The President is Missing by President Bill Clinton and James Patterson, to be published by Century on 4th June.

Kannur: Inside India's Bloodiest Revenge Politics by Ullekh N.P. – An Excerpt

Kannur, a sleepy coastal district in the scenic south Indian state of Kerala, has metamorphosed into a hotbed of political bloodshed in the past few decades. Even as India heaves into the age of technology and economic growth, the town has been making it to the national news for horrific crimes and brutal murders with sickening regularity. Ullekh N.P.’s latest book, Kannur: Inside India’s Bloodiest Revenge Politics draws a modern-day graph that charts out the reasons, motivations and the local lore behind the turmoil.

As Sumantra Bose, Professor of international and comparative politics, London School of Economics and Political Science, mentions in his foreword for the book, “Ullekh N.P. is uniquely placed to write this chronicle of Kannur, both as a native of the place and as the son of the late Marxist leader Pattiam Gopalan. Being an ‘insider’— and a politically connected insider…Ullekh tells the story of unending horror with deadpan factuality, tinged with compassion in his latest book, Kannur: Inside India’s Bloodiest Revenge Politics.”

Let’s read an excerpt from the book-

———–

The news that hits headlines from Kannur these days is mostly about its law-and-order situation. TV scrolls announce items such as these with great frequency: ‘One killed in Muslim League–CPI(M) clashes’; ‘Two hurt in RSS–CPI(M) fracas’; ‘CPI(M) man killed, RSS men nabbed’; ‘RSS youth hacked, 7 CPI(M) men held’; ‘PFI [Popular Front of India] activists attacked’; ‘District Collector calls all-party peace meeting’, and so on.

The crime bureau statistics, as of November 2016, show that forty-five CPI(M) activists, forty-four BJP–RSS workers, fifteen Congressmen and four Muslim League followers have been killed since 1991 in Kannur, besides a few other murders of the cadres of parties such as the PFI. Between November 2000 and 2016, the number of party workers killed in Kannur was thirty-one from the RSS and BJP, and thirty from the CPI(M), according to data obtained from the police by the independent news website 101reporters.com through a right-to-information request. While the RSS leaders claim that the CPI(M) are now doing to them what the Congress had done to the communists in the past, the CPI(M) leaders contest it, reeling off stats, and claiming that they have been forced to resist because the Hindu nationalists are hoping to effect a religious polarization through the politics of violence in order to reap electoral gains that have eluded them for long.

The latest numbers do not endorse the RSS’s claims of being a victim in this Left stronghold. Regardless, the Sangh has actively pursued a campaign, spiffily titled Redtrocity(short for Red Atrocity, referring to the reported high-handedness by the Marxists), as a counterweight to the series of accusations hurled against it for allegedly sowing religious hatred, perpetuating violence against non-conformists, triggering riots and deliberately aiding a mission to heighten communal hostilities.

Police records show that the RSS and the BJP have been at loggerheads not with the CPI(M)alone, but also with other parties, including the PFI and the Congress. Yet, equally laughable is the contention by the CPI(M) that it is portrayed as a villain without reason because it has only been engaging in acts of resistance and seldom in violent aggression.

Recent data show that from 1972 to December 2017, of the 200 who died in political violence in Kannur district—which accounted for the highest number of political crimes

in the state during the period, far ahead of other districts—seventy-eight were from the CPI(M), sixty-eight from the RSS–BJP, thirty-six from the Congress, eight from the Indian

Union Muslim League (IUML), two each from the CPI and the National Development Front (now called the PFI), while the rest were from other parties. Notably, of the total 193 political murder cases that took place in Kannur during the period, 112 of the accused were from the Sangh Parivar and 110 from the CPI(M).

The RSS–BJP argue that the escalation of hostilities started with the killing of an RSS worker on 28 April 1969, but the Marxists aver that the death was a denouement to a series of clashes stemming from the RSS’s support to a beedi baron who refused his workers a justified hike in salary and shut his business before floating two new companies. Media reports often show that more communist workers have died in Kannur than those belonging to any other party. The greatest irony in the RSS–CPI(M) fights is that the pro-Hindu Sangh Parivar has had no qualms about targeting CPI(M)-dependent Hindus, while the Marxists, the much-touted saviours of the proletariat, vehemently, so the story goes, go after the working classes who happen to be aligned with the Hindu nationalists.

Along Payyambalam beach, not far from the grave of K.G. Marar, one of the RSS’s topmost leaders in the state, is a grave of a twenty-one-year old man. Too young to die, that’s what visitors to the place would say. Sachin Gopalan died from sword injuries in July 2012. Allegedly, he was hacked by members of the radical Islamist Campus Front, a feeder organization of the PFI against which the National Investigation Agency (NIA) has now sought a ban for its anti-India activities. Gopal died at a hospital in Mangalore where he had arrived after shifting from one hospital to another in Kannur for want of better facilities. A student of a technical institute in the district, he was attacked when he had gone to a school for political work.

In the darkness of a late windswept evening, standing alone in the forbidding graveyard at Payyambalam, one is filled with evocative visions from the region’s chequered past and a violent present caught in the vortex of vendetta politics.

When I studied in a boarding school in Thiruvananthapuram, my classmates looked down on my hometown as Kerala’s Naples, a thuggish backwater; but then the district had

contributed two chief ministers (and one more later) as well as several luminaries to the state’s cultural, social, professional and political spheres.

I also came to be known as someone from the ‘Bihar of Kerala’. Later, I invented a rather self-deprecating phrase of my own: ‘the Sicily of Kerala’, factoring in the local omertà-

like code the Italian region was once known for. Poking fun at oneself does make sense, as it’s an effort to tide over the mental fatigue that sets in on being judged as a violent people, who are puritanical and foolish. Deep within, however, it hurts like a migraine.

The waves keep breaking hard on the shore like smooth knives on raw flesh.

———–

Our Impossible Love by Durjoy Datta – An Excerpt

Aisha, a late bloomer, has to figure out what it means to be a woman and to be desired. Danish feels time is running out for him and he’s going to end up as a nobody, as opposed to his overachieving, determined younger brother. Life takes a strange turn when Danish, the confused idiot, is appointed as the student counsellor to Aisha. Between the two of them they have to figure out love, life, friendship-most of all, themselves.

Our Impossible Love written by the bestselling author, Durjoy Datta presents, a story that showcases Life the way it is and Love the way it should be.

Let’s read an excerpt from this book.

———–

Danish Roy

They keep telling you, you’re unique, you’re different, you have a calling, a talent, a miracle inside of you. I had bought into this theory for a really long time. But no more. I was ordinary and there was no point waiting for that hidden genius in me to bubble to the surface. I would not discover my yet unexplored talent for painting, or interpreting ancient languages, or being a horse whisperer, or interpreting foreign policy at thirty.

And I think I would have been okay with it, or at least as okay as everyone else is with their ordinariness, had it not been for my overachieving little brother, my parents’ favourite, who was wrecking corporate hierarchies like he was born to do so. Only last year, he got into the top 30 under 30 (at 21) in Forbes magazine for being a start-up prodigy. Fresh out of IIT Delhi, his crazy idea of sending high packets of data over Bluetooth in a matter of seconds sent potential investors in a tizzy. He was always in a tie-suit now, carrying leather folders and taking late night flights to meetings where capital flow, structural accounting and other terrifying things are discussed.

I’m two years older than him and I hadn’t even won a spoon race in my life.

Quite understandably, I was a bit of an embarrassment to my parents—my father was a high-ranking official in the education ministry, and my mother, a tenured physics lecturer at Delhi University. It’s not that they didn’t love me, of course they did, but it was only because I was their son and they were programmed to love me more than themselves. But yeah, they loved Ankit more, and I didn’t blame them.

Even I loved him more.

I was still struggling to complete my graduation in psychology (a subject my parents had chosen for me) from a college no one knew about, including the government, I presume. I was twenty-three and I had never been employed, a situation that didn’t look like would change in the near future. It was more likely I would flunk my final exams too. Flunking exams by ridiculous margins was my superpower!

I was the most self-aware dumb person I had ever met.

Throw me a Suduko and you could study human behaviour in hostage situations. Medieval torture had nothing on me but keep a mathematics exam paper in front of me and I would start shitting bricks.

————

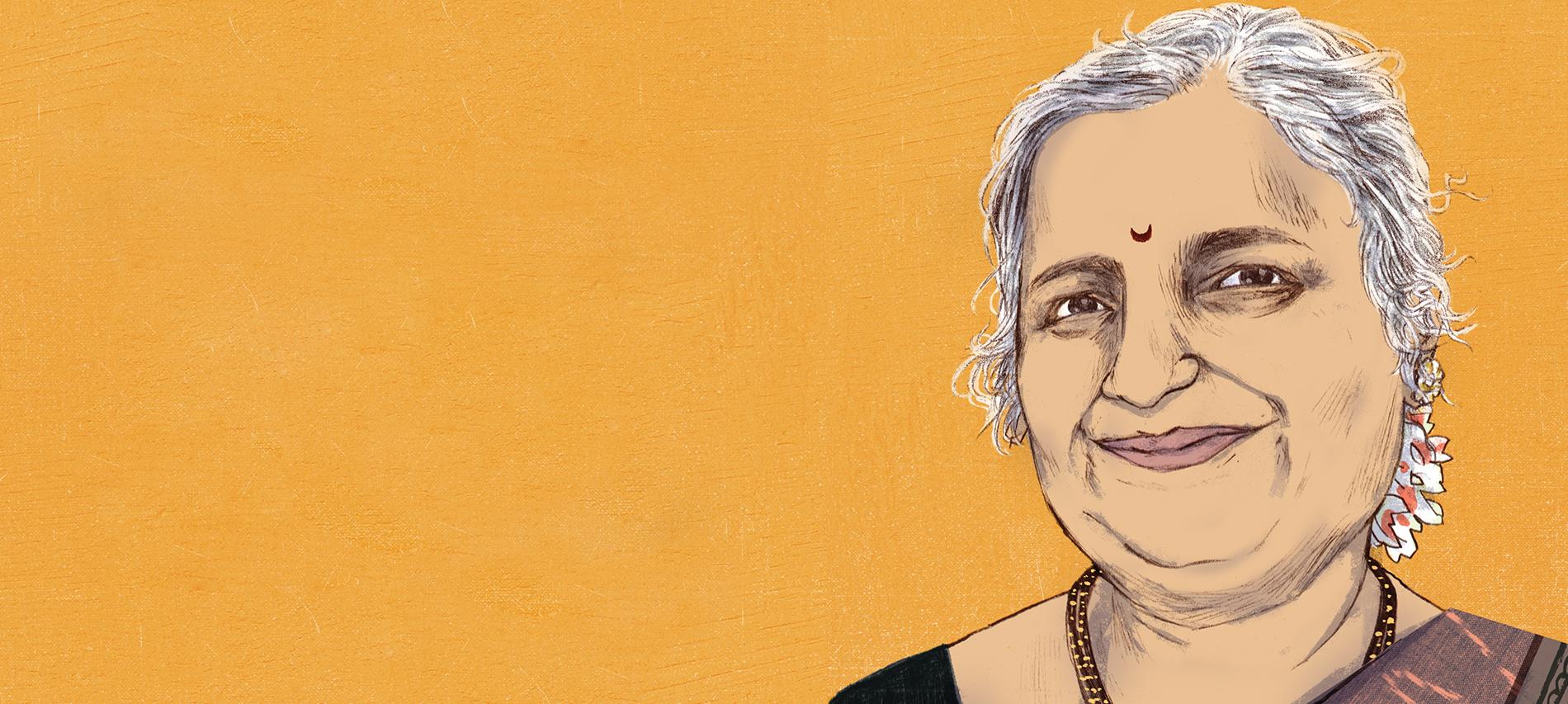

Here, There and Everywhere: 5 Sudha Murty Stories you Must Read

Wearer of many hats-philanthropist, entrepreneur, computer scientist, engineer, teacher-Sudha Murty has above all always been a storyteller extraordinaire.

Here, There and Everywhere is a celebration of her literary journey and is her 200th title across genres and languages. It brings together her best-loved stories from various collections.

Here are 5 stories by her that you must read, from this collection.

Sudha Murty talks about her journey as a writer in A Tale of Many Tales. She mentions how her mother would force her to sit down and write about the events of her day, and how this ultimately lead to ‘inadvertently improving her expression and adding clarity to her ideas’.

R.H. Kulkarni, a young medical doctor was posted to a small dispensary in a quiet village. One night, during a heavy rain, he heard a knock on his door. Four men wrapped in woolen rugs stood with sticks in their hand. They forced him out of his house and made him sit in a bullock cart. Where were they taking him? Read this gripping story to find out more.

A middle aged man brings an old man with no friends or family into the authors office, saying he met him on the bus stop and needed help in relocating him to an old-age home. A few months later, the old man is in hospital. When she goes to visit him, she sees the same middle-aged man there as well. Who is he and why is he there?

On an overcrowded train from Bombay to Bangalore, the author comes across a young girl in torn clothes without a ticket. She pays the ticket collector the fare for the girl but is unable to get her to talk. When she finally does, she finds out she’s a run away with nowhere to go. She helps her find place in a shelter in Bangalore not realizing then, the long way the girl will go from there, all thanks to a simple train ticket.

Sudha Murty tells us the story of being the only female in her engineering college. She shares her struggles-first in being allowed to actually attend the college, and then those she faced while being there. However, she was adamant to do complete her course and ended up doing better than most of the boys. She joined college as a scared teenager but left as a confident and bright young engineer.

5 Quotes from Daisy Khan on Gender Equality

Born with Wings is a powerful, eye-opening account of Daisy Khan’s inspiring journey of self-actualization. Guided by her faith, Daisy Khan is a women’s advocate and has devised innovative ways to help end child marriage, fight against genital mutilation, and, most recently, educate young Muslims to resist the false promises of ISIS recruiters.

Here are some of Daisy Khan’s thoughts on Islam and gender equality:

The Quran, believed to be the central religious text of Islam, lays great emphasis on upholding a woman’s dignity no matter what the circumstances.

By carefully studying the holy Quran, Daisy Khan was convinced that gender equality has always been a part of Islam. However, because of misguided interpretations of the Quran especially by men, women have suffered several injustices.

Daisy Khan points, that in the religious scriptures of Islam, nowhere is it stated as a rule that a woman has to maintain her modesty by wearing hijabs or burqas.

Muslim women have historically always had rights. Fourteen hundred years ago, when these rights were not granted to even Western women, Muslim women have had the right to property, the right to divorce, the right to inheritance and the right to have a career simply because men and women are considered equal in Islam. The situation is quite different today simply because of faulty interpretations of the Quran’s verses.

Tradition by Brendan Kiely – An Excerpt

The students at Fullbrook Academy are the elite of the elite, famous for their glamour and excess. Their traditions are sacred. But they can hide dark and dangerous secrets.

From New York Times bestselling author Brendan Kiely, comes Tradition, a stunning novel that explores various dangerous traditions that exist in this prestigious boarding school.

Take a sneak peek into what goes on at The Fullbrook Academy by reading an extract from the novel now!

———–

For the record . . .

JAMES BAXTER

Most people don’t get second chances. I wasn’t sure I deserved one. I wasn’t sure I even wanted one. But I got one: Fullbrook Academy. This is what I did with it.

JULES DEVEREUX

I once heard another girl put it like this: This is a boys’ school and they accept girls here too. At Fullbrook, they told us to be ready to take on the world, but then they told us to do it quietly. What if I wanted to be loud? What if I needed to be?

The night everything changed . . .

JULES DEVEREUX

I’m fighting for breath and all I can do is look up and see the white flame of moonlight outlining each branch, every leaf. I’m in the dirt, again, shoulder against the tree, the shock of air so cold it seizes my bones. I can still feel his grip on my arm, as if he’s still here, shackling me to the trunk with his hands and his weight, but he’s not. He’s gone. I’m so cold. I’m shaking, but it feels like it’s this tree and the sky above that are shaking, that are blurry, unreal, no longer what they were. It’s as if I’m naked, but I’m not. It’s as if the ground is swinging up to slap me, but it’s not. I collapse by the edge of the bluff. There are still voices in the woods behind me. Voices down along the far end of the bluff. Voices in the night air like invisible birds screeching in the wind.

There’s a voice inside me, too. It’s mine, I think, but it doesn’t sound like me. It’s me and it’s not me. It grows louder and louder, barking, bellowing up from somewhere and squeezing my head with noise. It’s me and it isn’t, or it’s me splitting in two, and this other voice, this new voice, keeps shouting. Run, it says. Run, run, run.

I’m so close to the cliff edge, I could crawl forward and drop, crouch on one knee by the side of the pool like I did when I first learned to dive, but I’m hundreds of feet in the air, and the voice tells me to back up. I obey. It tells me to stand, and I use the tree to help me to my feet. Run, it says again, and I do, into the woods, down the far path, away from the party, away from the other voices, away from everyone. I know where I’m going, but I still feel lost. Alone. I just want to get home, though the word means nothing now. Just because I live there doesn’t mean it’s somewhere safe.

JAMES BAXTER

I can’t believe this, but I’m so out of breath I have to crouch down and lean against the back wall of the girls’ dorm, just to put some air in my lungs. Damn, it hurts. But you can’t lug a passed-out person through the woods, across campus, get her up through the bathroom window, and not want to collapse. Even if you’re me. And even if I did get some help.

I know she thinks I’m an asshole, and I didn’t do it to change her mind. I just did it because it was the right thing to do and I knew it was the right thing to do, and it was the first time in a year I’d felt so certain I knew right from wrong—that I had to do the right thing and forget all the rest.

If you care about a person, my ex-girlfriend used to tell me, don’t just tell her. Show her. Show up, listen, and act so she knows you heard her. Seems so simple the way she put it, but it’s never that simple. An avalanche of other pressures buries that wisdom most days, all days, except this night, when, for some reason, I heard that advice strong and true, like a wind through the eaves of the old wooden rooftop above me.

Way up in the sky the man in the moon has something like sad eyes, as if his pale face gazes down with pity, as if he wishes something better for us, or maybe wishes we ourselves were the ones who were better. I’m sure I’m sober, not drunk, just going a little crazy to think like that, but I think it anyway, because I feel that way. Sad. Like this whole stupid paradise, this very good school, is nothing but a fancy promise, a broken one, a big lie. And worse, that I’m actually a part of it.

———–

Still Me by Jojo Moyes – An Excerpt

Jojo Moyes, the author of bestsellers Me Before You and After You brings the third Lou Clark novel, Still Me. The third book sees Lou arrive in New York to start a new life. What Lou doesn’t know is she’s about to meet someone who’s going to turn her whole life upside down. Because Josh will remind her so much of a man she used to know that it’ll hurt. Lou won’t know what to do next, but she knows that whatever she chooses is going to change everything.

Let’s read an excerpt from the book, Still Me.

———–

‘Reasons for travel, ma’am?’ The moustache twitched with irritation. He added, slowly: ‘What are you doing here in the United States?’

‘I have a new job.’

‘Which is?’

‘I’m going to work for a family in New York. Central Park.’

Just briefly, the man’s eyebrows might have raised a millimetre. He checked the address on my form, confirming it.

‘What kind of job?’

‘It’s a bit complicated. But I’m sort of a paid companion.’

‘A paid companion.’

‘It’s like this. I used to work for this man. I was his companion, but I would also give him his meds and take him out and feed him. That’s not as weird as it sounds, by the way – he had no use of his hands. It wasn’t like something pervy. Actually in my last job it ended up as more than that, because it’s hard not to get close to people you look after and Will – the man – was amazing and we . . . Well, we fell in love.’ Too late, I felt the familiar welling of tears. I wiped my eyes briskly. ‘So I think it’ll be sort of like that. Except for the love bit. And the feeding.’

The immigration officer was staring at me. I tried to smile. ‘Actually, I don’t normally cry talking about jobs. I’m not like an actual lunatic, despite my name. Hah! But I loved him. And he loved me. And then he . . . Well, he chose to end his life. So this is sort of my attempt to start over.’ The tears were now leaking relentlessly, embarrassingly, from the corners of my eyes. I couldn’t seem to stop them. I couldn’t seem to stop anything. ‘Sorry. Must be the jetlag. It’s something like two o’clock in the morning in normal time, right? Plus I don’t really talk about him anymore. I mean, I have a new boyfriend. And he’s great! He’s a paramedic! And hot! That’s like winning the boyfriend lottery, right? A hot paramedic?’

I scrabbled around in my handbag for a tissue. When I looked up the man was holding out a box. I took one. ‘Thank you. So, anyway, my friend Nathan – he’s from New Zealand – works here and he helped me get this job and I don’t really know what it involves yet, apart from looking after this rich man’s wife who gets depressed. But I’ve decided this time I’m going to live up to what Will wanted for me, because I didn’t get it right, before. I just ended up working in an airport.’

I froze. ‘Not – uh – that there’s anything wrong with working at an airport! I’m sure immigration is a very important job. Really important. But I have a plan. I’m going to do something new every week that I’m here and I’m going to say yes.’

‘Say yes?’

‘To new things. Will always said I shut myself off from new experiences. So this is my plan.’

The officer studied my paperwork. ‘You didn’t fill the address section out properly. I need a zip code.’

He pushed the form towards me. I checked the number on the sheet that I had printed out and filled it in with trembling fingers. I glanced to my left, where the queue at my section was growing restive. At the front of the next queue a Chinese family was being questioned by two officials. As the woman protested, they were led into a side room. I felt suddenly very alone.

The immigration officer peered at the people waiting. And then, abruptly, he stamped my passport. ‘Good luck, Louisa Clark,’ he said.

I stared at him. ‘That’s it?’

‘That’s it.’

I smiled. ‘Oh, thank you! That’s really kind. I mean, it’s quite weird being on the other side of the world by yourself for the first time, and now I feel a bit like I just met my first nice new person and –’

‘You need to move along now, ma’am.’

‘Of course. Sorry.’

I gathered up my belongings and pushed a sweaty frond of hair from my face.

‘And, ma’am . . .’

‘Yes?’ I wondered what I had got wrong now.

He didn’t look up from his screen. ‘Be careful what you say yes to.’

————-

Supreme Whispers by Abhinav Chandrachud – An Excerpt

In Abhinav Chandrachud’s latest book, Supreme Whispers: Conversations with Judges of the Supreme Court of India 1980-1989, Chandrachud relying on the typewritten interviews of a brilliant young American scholar, George H. Gadbois, Jr. who conducted over 116 interviews with more than sixty-six judges of the Supreme Court of India provides a fascinating glimpse into the secluded world of the judges of the Supreme Court in the 1980s and earlier.

Let’s read an excerpt from this book.

———–

The broad sense one gets is that dissent is generally frowned upon at the Supreme Court, and dissents get written only in the rarest of cases involving irreconcilable conflict. Chief Justice M. Hidayatullah admitted to ‘ragging’ two of his colleagues who dissented from his view in the very first case they heard together, because he was responsible for bringing them to the court. However, he did feel reassured by their independence. Justice P.B. Gajendragadkar, known for his pro-labour leanings, once wrote a draft judgment with which his colleague, Justice N.H. Bhagwati, disagreed. Bhagwati suggested that Gajendragadkar make some changes to the judgment in order to secure Bhagwati’s agreement to sign off on it. Gajendragadkar refused to change a word of his draft. Bhagwati signed the judgment anyway, since another judge on the bench, Justice S.K. Das, had also agreed to sign it, and Bhagwati did not want to dissent. In February 1983, a bench of two judges had said that in a death penalty case if the person convicted is not executed within two years, then the sentence automatically stands commuted to life imprisonment. Shortly after this judgment was delivered, it was overruled by a bench of three judges of the court. Justice A. Varadarajan believed that if the two judges who had delivered the judgment in the earlier case had sat with the three judges who decided the later case, even they would have been convinced to be a part of the majority in the later case.

Justice H.R. Khanna, arguably one of the greatest dissenters of all time at the Supreme Court, who disagreed with the majority view in the Habeas Corpus case, admitted that he did not dissent in one of the early cases he heard in the court even though he disagreed with the view of the majority. The Supreme Court’s judgment in that case had the effect of raising car prices. Although he ‘did not feel happy with the view they took’, Khanna agreed with the judgment of the majority because he ‘did not think it proper to strike a discordant note at the very beginning’ of his judgeship at the Supreme Court. ‘The atmosphere in court’ at the time, noted Khanna, ‘was of general cordiality.’ This, of course, did not stop Justice Khanna from dissenting in the Habeas Corpus case, where a majority of the judges of the bench held that the right to seek the writ of habeas corpus and to challenge arbitrary arrest and detention could be suspended during an Emergency. Dissent at the Supreme Court, then, seems to be reserved for the most egregious and exceptional circumstances.

‘I did not believe in writing separate or dissenting judgments for nothing,’ wrote Justice P.N. Shinghal in a letter to Gadbois. ‘So if I have written dissents,’ he continued, ‘they were necessary to place my irreconcilable views on record.’ Justice A.C. Gupta was critical of his colleagues who were eager, in big cases, to write separate judgments. He pointed out that Justice E.S. Venkataramiah wrote a judgment of over 300 pages in the Judges case. Justice Krishna Iyer felt that writing a dissent gained little, and did not serve much purpose. He stressed that the whole court was very congenial, ‘delightfully united’, and there was a ‘happy sense of cooperation’ prevalent at the time. He believed that divided decisions were not as good as unanimous ones. In fact, who is writing the majority judgment for the court also matters. Justice P. Jaganmohan Reddy believed that the majority judgment of the Supreme Court in the Bank Nationalization case should not have been written by Justice J.C. Shah because Shah had delivered the judgment in an earlier case in which the court had taken a seemingly contrary view. He felt that somebody else should have written the majority judgment or even a concurring judgment. The majority judgment of Shah was extensively discussed by the judges prior to being delivered, and several passages were removed and added by other judges. The court wrote one judgment in order to achieve clarity and avoid contradictions.

______________________________________________________________________________