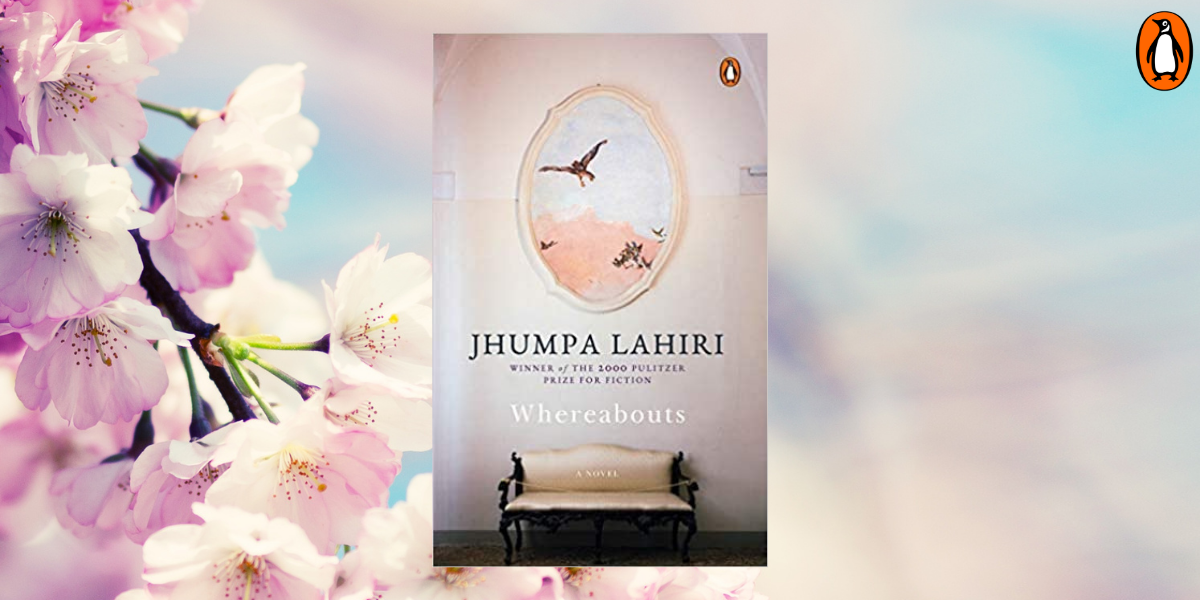

Exuberance and dread, attachment and estrangement: in this novel, Jhumpa Lahiri stretches her themes to the limit. The woman at the center wavers between stasis and movement, between the need to belong and the refusal to form lasting ties. The city she calls home, an engaging backdrop to her days, acts as a confidant: the sidewalks around her house, parks, bridges, piazzas, streets, stores, coffee bars. We follow her to the pool she frequents and to the train station that sometimes leads her to her mother, mired in a desperate solitude after her father’s untimely death. In addition to colleagues at work, where she never quite feels at ease, she has girl friends, guy friends, and “him,” a shadow who both consoles and unsettles her. But in the arc of a year, as one season gives way to the next, transformation awaits. One day at the sea, both overwhelmed and replenished by the sun’s vital heat, her perspective will change. This is the first novel she has written in Italian and translated into English. It brims with the impulse to cross barriers. By grafting herself onto a new literary language, Lahiri has pushed herself to a new level of artistic achievement.

Here is an excerpt from the book Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahiri:

The city doesn’t beckon or lend me a shoulder today. Maybe it knows I’m about to leave. The sun’s dull disk defeats me; the dense sky is the same one that will carry me away. That vast and vaporous territory, lacking precise pathways, is all that binds us together now. But it never preserves our tracks. The sky, unlike the sea, never holds on to the people that pass through it. The sky contains nothing of our spirit, it doesn’t care. Always shifting, altering its aspect from one moment to the next, it can’t be defined.

This morning I’m scared. I’m afraid to leave this house, this neighborhood, this urban cocoon. But I’ve already got one foot out the door. The suitcases, purchased at my former stationery store, are already packed. I just need to lock them now. I’ve given the key to my subletter and I’ve told her how often she needs to water the plants, and how the handle of the door to the balcony sometimes sticks. I’ve emptied out one closet and locked another, inside of which I’ve amassed everything I consider important. It’s not much in the end: notebooks, letters, some photos and papers, my diligent agendas. As for the rest, I don’t really care, though it does occur to me that for the first time someone else will be using my cups, dishes, forks, and napkins on a daily basis.

Last night at dinner, at a friend’s house, everyone wished me well, telling me to have a wonderful time. They hugged me and said, Good luck! He wasn’t there, he had other plans. I had a nice time anyway, we lingered at the table, still talking after midnight.

I tell myself: A new sky awaits me, even though it’s the same as this one. In some ways it will be quite grand. For an entire year, for example, I won’t have to shop for food, or cook, or do the dishes. I’ll never have to eat dinner by myself.

I might have said no, I might have just stayed put. But something’s telling me to push past the barrier of my life, just like the dog that pulled me along the paths of the villa. And so I heed my call, having come to know the guts and soul of this place a little too well. It’s just that today, feeling slothful, I’m prey to those embedded fears that don’t dissipate.