Veteran musician and sarod maestro, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan, in his Master on Masters, writes a deeply personal book about the lives and times of some of the greatest icons of Indian classical music. Having known these stalwarts personally, he recalls anecdotes and details about their individual musical styles, bringing them alive.

In writing about them, the maestro transcends the Gharana and north-south divide and presents portraits of these great artists that are drawn with affection, humour and warmth.

Have you heard these legends before?

Category: Specials

7 Quotes by Perumal Murugan that Describe a Difficult Childhood

Perumal Murugan’s works provide a poignant commentary on the religious and caste practices prevalent in the society. His stories vividly capture the pain a person from the lower strata of society goes through every day.

His novel Seasons of the Palm, which was shortlisted for the Kiriyama Award, is merciless in its portrayal of the daily humiliations of untouchablility. It also evokes the grace with which the oppressed come to terms with their dark fate. Shorty, the central character of Murugan’s novel is one such young untouchable who is in bondage to a powerful landlord.

Here are a few quotes from the book that will give you a glimpse of Shorty’s hardships:

Being Awakened by a Stinging Whiplash

When You Can’t Wash Off Your Stink

Untouchable and Barred from Touching

When the Bare Necessities Turn into Luxury

A Paid Slave

Not-so-Good-Morning

When Your Days Are Like Empty Bowls

Aren’t they painful yet powerful? Tell us what do you think.

A Peek into a Reader’s World

Books are fascinating! They house many worlds, people, and emotions in them. And people who read them, i.e.: booklovers, slowly begin to embody these worlds. The reader often walks into the world of a book, but have you ever thought about how a book or its story become a part of a reader’s daily life? Has it ever happened to you that a story or character’s words seemed most appropriate in your life situation? (Happens to us every day!)

As the day of books is upon us, we decided to take you through some daily life situations where words from a book seemed to fit in all too perfectly.

When your always hungry colleague announces it’s lunch time during a meeting.

When your BFF throws you a Draw 4 card in UNO. Oh, the betrayal!

Your colleague when you need to stay back late. On a Friday.

When your in-laws decide to stay at your place for some time.

When you stay away from home for the first time and all you can cook is Maggi.

The salesman trying to get you to buy that Rs. 8,000 shawl.

Your dog, when he doesn’t care you are going to punish him.

Can you relate?

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan – A Bio

A distinguished maestro in the field of playing the sarod, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan is popularly known as the “Sarod Samrat“. He is the sixth generation sarod player in his family. The credit of modifying the sarod as a classical instrument goes to his ancestors of the Bangash lineage originating from Senia Bangash School of Music.

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan was born on 9th October 1945 at Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh. His father Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan was a musician in the court of the royal family of Gwalior. Hafiz Ali Khan received training from the descendants of Miyan Tansen, considered one of the greatest musicians produced by India. Amjad Ali Khan was the youngest son in his family. His first tutor was his father and he began playing at a very young age.

Amjad Ali Khan gave his first solo recital at the age of twelve. His love for the instrument and passion for music made him famous and one of the greatest sarod players of all time. Amjad Ali Khan has a unique way of playing the sarod with his fingernails instead of his fingertips. This gives a clear ringing sound but is the most difficult technique to apply on the sarod. Khan has composed many ragas of his own like Kiran Ranjani, Haripriya Kanada, Shivanjali, Shyam Shri, Suhag Bhairav, Lalit Dhwani, Amiri Todi, Jawahar Manjari and Bapukauns. He has acquired international acclaim by composing for the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, a piece titled Tribute to Hong Kong. The other musicians involved with this project were guitarist Charley Byrd, Violinist Igor Frolov, Suprano Glenda Simpson, Guitarist Barry Mason and UK Cellist Matthew Barley.

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan has given performances in Carnegie Hall, Royal Albert Hall, Royal Festival Hall, Kennedy Center, The House of Commons, Mozart Hall in Frankfurt, Chicago Symphony Center, St. James Palace and the Opera House in Australia. The maestro has received Honorary Citizenship in the states of Texas, Massachusetts, Tennessee and the city of Atlanta.

Amjad Ali Khan is the first north Indian artist to have performed in honour of Saint Thyagaraja at the Thiruvaiyur shrine. He has been a recipient of many awards like Padmashree Award, Sangeet Natak Academy Award, Tansen Award, UNESCO Award, UNICEF National Ambassadorship, Padma Bhushan, International Music Forum Award, etc.

Amjad Ali Khan has two sons who are promising sarod players, hinting that the legacy shall live on.

What does a City Ravaged by War Look Like?

Everyday hearing the news makes war seem like a very real possibility. But do we really know what happens to a city when it is hit by war?

In Exit West – a heartrending story of love in the time of a refugee crisis – Mohsin Hamid paints a searing picture of a city torn by war and the destruction that the people go through.

Here are some of heartbreaking moments from Mohsin Hamid’s new novel.

Do you, too, have a war-time experience to share? Share with us!

The Woman Jinnah Fell in Love With

The news of Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s marriage to Ruttie Petit in 1918 shook pre-partitioned India. Everyone wondered about this woman who had made the serene yet strait-laced national leader fall in love with her.

Sheela Reddy in her exhaustive Mr. and Mrs. Jinnah paints an interesting portrait of the enchanting Ruttie Petit Jinnah.

Wasn’t she enigmatic? Tell us how you perceive Ruttie Jinnah.

STAR: The Mantra to Develop a Caring Mindset

Subir Chowdhury has helped numerous corporations to climb up the ladder of success in the course of his career. However, he has observed that while some companies benefit only marginally from the training others do exponentially well.

Chowdhury credits ‘a caring mindset’ as the difference in the performance of the two companies. Furthermore, he states that a caring mindset contains four facets.

The four facets make up a useful and memorable acronym: STAR. Here’s what it stands for:

Do you agree with Subir Chowdhury?

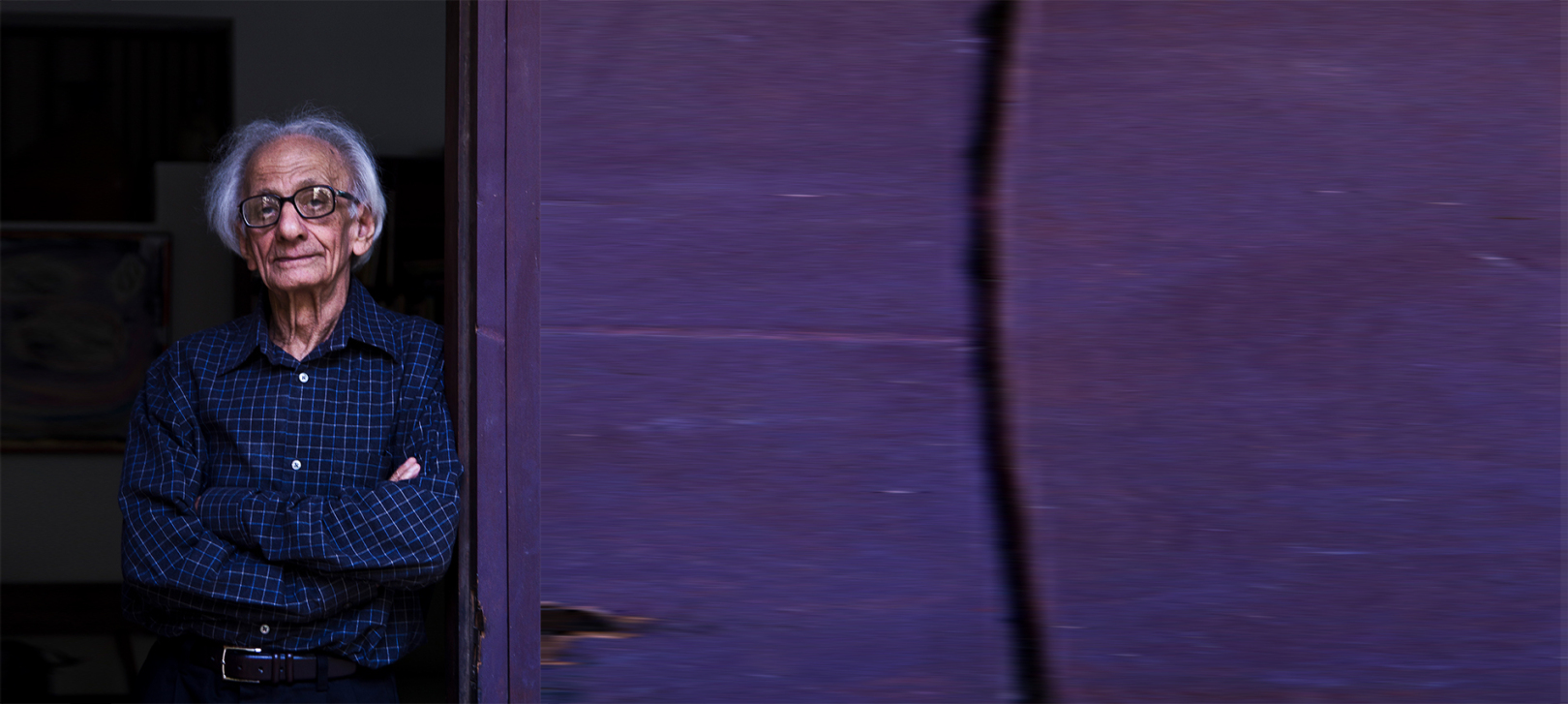

In Conversation with Krishna Baldev Vaid

We recently spoke to the author of None Other, the august 89-year old Krishna Baldev Vaid. He is well known for his books The Broken Mirror, Steps in Darkness and many more.

Below are a few questions we asked Vaid to know more about his writing process.

When you get an idea for a book, how does it form into a story? Please share your writing process with us.

It differs in details from piece to piece, from novel to novel, from play to play but essentially, it assumes the urgency and intensity of an obsession that elevates me to a level of receptivity, that is extraordinary if not abnormal, to intuitions, perceptions, choices of words and phrases and puns and euphonious effects, in short a style suitable to the occasion. The emphasis is never on story as such. My stories, both short and long, are never mere stories; my novels and plays do not aim at telling intricate and interesting and eventful stories. They do not require a well-designed plot. They create an atmosphere, an alternative reality, if you will, a universe of words and sounds and suggestions and characters that are both familiar and strange, normal as well as abnormal, mundane and magical, real and unreal, just as in dreams and nightmares.

Do you have any writing rituals that you follow?

I am afraid I do not have any writing rituals except perhaps a room of my own, a closed door, a wall in front of me, a space to pace up and down, silence, sometimes low and slow classical instrumental, preferably sarod, music. I tend to make fun of writing rituals in my novels and stories such as ”Bimal Urf Jayein To Jayein Kahan” (”Bimal in Bog” in English) and ”Doosra Na Koi” (”None Other” in English).

When I was young, I had a somewhat romantic association with writing and artistic rituals. In old age, every elderly movement and gesture and activity automatically and inevitably becomes ritualistic. You don’t need any other rituals.

How do you pick books that you want to translate? Is there a reason behind that choice, such as for Alice in Wonderland?

I am not a professional and a prolific translator into English or Hindi. I think I have translated more of my own stuff in Hindi into English than other writers’—alive or dead. I tend to believe I would have been less of a self-translator into English if there had been an active band of good professional translators into English from Hindi. Perhaps, in that case, I would still have used my bilingualism for doing some selective translations of some modernistic Hindi fiction and poetry as love’s labour or out of a sense of duty; I don’t know.

Two of my dear friends, Nirmal Verma and Srikant Varma, asked me to translate two of their novels, ”Ve Din” (Nirmal) and ”Doosri Baar” (Srikant), and I complied because I liked their work, but I did not ‘pick’ them. In the case of ”Alice in Wonderland”, I chose it for translation into Hindi because of its status as a classic, not only as a children’s book but for ‘children’ of all ages and, I believe, nationalities. I used to read it to my three little girls as they were growing up. Besides, the only great version available in Hindi was a great adaptation by a great Hindi poet, Shamsher Bahadur Singh—”Alice Ascharya Lok Mein.” I wanted to do a translation of the complete original text. The third major translation of an important book-long Hindi poem that I did was ”Andhere Mein” (”In The Dark”) by Muktibodh. I selected it because of my admiration for it as a modern classic by a great Hindi poet who died in splendid neglect except as a cult poet for the discerning younger Hindi poets, without a published collection of his own poetry.

I chose two plays of Samuel Beckett—”Waiting for Godot” and ”Endgame”—in 1968, before he became a noble laureate, because Beckett was my favourite modern writer. I wrote to him for permission while I was a visiting professor in English at Brandeis university. He wrote back a brief but gracious post-card from Paris after a couple of months, granting me permission even though he assumed I’d do my translation from his own English version of those plays written originally by him in French. I wrote back thanking him and mentioning that his assumption was correct even though I assured him that even though my French was inadequate, I’d also take into account his French original of the plays.

In addition to these three Hindi books, I also translated some Hindi poems and stories of some important Hindi writers, only one of whom—Ashok Vajpeyi—is alive: Shamsher Bahadur Singh, Srikant Varma, Muktibodh, Upendranath Ashk, Hari Shankar Parsai, Ashok Vajpeyi. All these have been published in English magazines but not collected in a book.

The only other notable translation into Hindi that I have done was commissioned by the French embassy in Delhi—it was Racine’s ”Phaedra”. I told them my Hindi translation would be from a standard English version of the original French and that I’d consult the original French with the help of my inadequate French. My Hindi version was published by Rajkamal Prakashan and was staged in Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal, and Delhi under the direction of an important and renowned French director, M. Lavadaunt.

How do you decide which language to write in and which one to translate into? And why?

This decision was made by me rather early in my life during my final year of M.A. in English at Govt. College, Lahore when I was only nineteen years old and living under the menacing shadow of the partitioned independence of India into two countries, India and Pakistan. My heart was set on being a creative writer, a fictionist. I already knew that I would have to do something else for earning a living if I wanted to write on my own terms without making any compromise with anybody. I did not want to write in English, even though I was fairly good in it and knew that I’d get better, because I didn’t consider it as an Indian language and did not dream in it. I didn’t want to choose Punjabi as my medium of creative expression, even though it was my mother tongue, because I didn’t consider it rich enough. The choice was between Urdu, which I was also good at thanks to my proficiency in Persian, and Hindi which I had almost entirely taught myself thanks to the similarity of its and Urdu’s grammar and syntax. With more of Hindi reading and the help of a good dictionary and with an openness to Urdu and Persian for the enrichment of my vocabulary, I could forge a style of my own that might even be better than standard stultified Hindi, or Urdu for that matter. I soon was able to achieve a style of my own free from the stiffness of both standard Hindi and Urdu and also the simplistic hotch-potch of the so-called Hindustani.

English is the only language I can translate my own Hindi books into; my own kind of Hindi is the only language that I can translate any English book into. Since I translate only what I like and want to and since I do not do it for my living, I do not do much translation. And now I am approaching the end and the final goodbye to all this.

Does the translation process differ when you are translating a book by an author other than yourself?

Yes, it does. If the other author is alive, you can refer your questions and problems and enigmas to him/her if he/she is easily accessible. If the author is dead or distant, metaphorically or really, you may either use your own discretion or consult an expert in that language or on that author.

If it is your own stuff that you are rendering into another language that you know well, you have only to refer to yourself for all questions and problems and enigmas and uncertainties. So in one sense you are free and self-sufficient but in another sense you are as lonely as you were when you were writing your original book. Of course, if in the course of self-translating if a new flash comes to you, you may as well take advantage of it without any compunction. You may end up adding to and subtracting from your original book. This addition and subtraction may help or harm the book but you are greater liberty in this case. Some writer friends of mine feel absolutely free to change their original books while translating them. Qurratullain Haider, an Urdu writer-friend who is no more was one such novelist of great merit. I did not read her own free self-translations into English but I did read several of her Urdu novels and was aleays charmed and impressed.

In my own case, when I was doing my own novel, ”Bimal Urf Jaayein To Jaayein Kahan”, into ”Bimal in Bog” for my friend P. Lal’s publishing outfit, Writers Workshop, I gave myself the freedom to welcome new ideas and flashes and linguistic arrangements and puns, etc., so that I had no objection when he changed ‘Translated by the author’ to ‘Transcreated by the author’. Even otherwise it seems to me now that all good translations are, to varying degrees, transcreations.

Are the themes of your writings related to your life experiences?

Perhaps, what you really meant to ask was: Are your novels and stories and plays autobiographical? But let me first answer your question as you phrased or framed it. The themes of one’s writings are always related to one’s life experiences. Even one’s entirely imagined themes are related in some way or other to one’s life experiences because one’s imagination is also shaped and determined by one’s own life experiences. Besides, all human experiences have an element of underlying universality that is a unifying factor which overrides apparent diversity. At the same time, every autobiographical detail undergoes an alchemical transformation in art. The tree or the flower you see with your eyes in real life is never the same as the one you describe or paint or sculpt or sing in your novel or paint in your picture or sculpt in your sculpture or sing in your music. The same is true of any feeling or emotion or action or happening, come to think of it. Even the most autobiographical detail undergoes a change through the alchemy of imaginative and creative writing.

7 William Wordsworth Quotes that will Brighten Your Weekend

Born on 7 April 1770 in Cockermouth, Cumberland, William Wordsworth debuted as an author in 1787 when he published a sonnet in The European Magazine.

As a youngster, he was encouraged by his father to learn large portions of verse, by authors such as Shakespeare and Milton.

In 1793, Wordsworth published his first set of poems in a collections titled An Evening Walk and Descriptive Sketches. In 1795 after receiving an endowment of £900 from Raisley Calvert, he decided to pursue a career as a poet. With Samuel Taylor Coleridge, he published Lyrical Ballads in 1798 and launched the Romantic Age in English literature. Wordsworth was regarded as Britain’s Poet Laureate from 1843 until his death in 1850.

Today, as we celebrate his 247th birthday, here are some of his profound words.

Do you have a favourite quote by William Wordsworth?

5 Quotes by Jhumpa Lahiri on Books and Their Covers

We often hear, “do not judge a book by its cover.” Perhaps not in judging the book entirely, but the cover does form an important visual relationship to the book

Jhumpa Lahiri explores this relationship of text and image in her latest book, The Clothing of Books.

Here are some intriguing quotes by Jhumpa Lahiri on the covers of books:

Probing the complex relationships between text and image, author and designer, and art and commerce, Jhumpa Lahiri explains what book covers and designs have come to mean to her in The Clothing of Books.