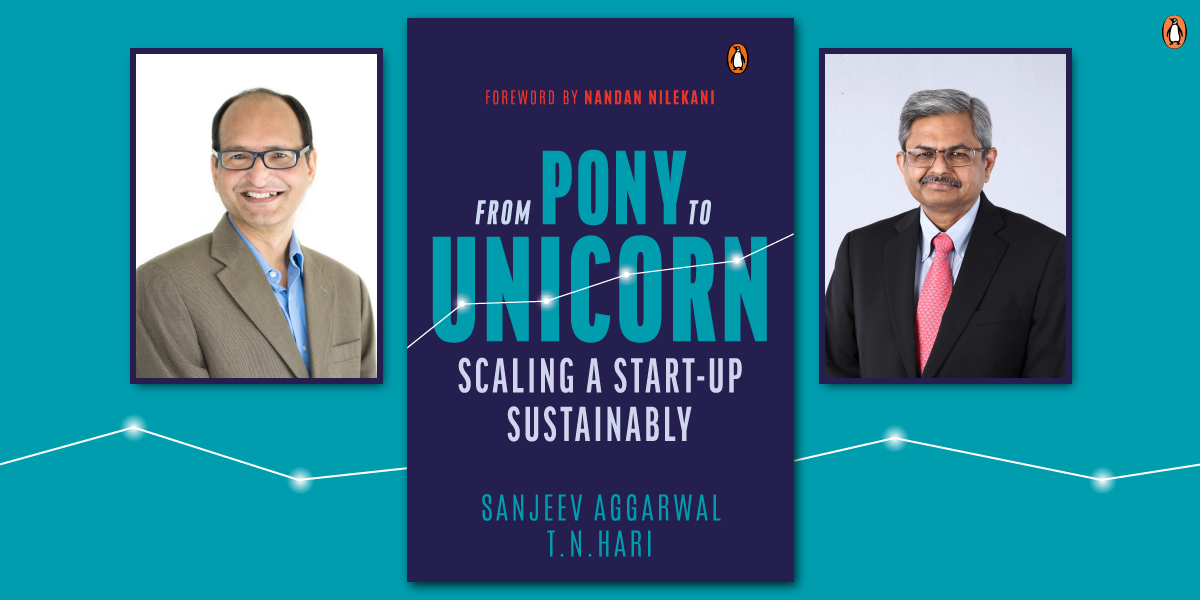

The journey of a business-from a small start-up to a large company ready for an initial public offering (IPO)-is fraught with pitfalls and landmines. To scale a company, one needs to do more than just expand distribution and ramp up revenue. From Pony to Unicorn lucidly describes the X-to-10X journey that every start-up aspiring to become a unicorn has to go through. The book effortlessly narrates the fundamental principles behind scaling.

Today, we are in conversation with the authors of the book, Sanjeev Aggarwal and T.N. Hari, who are both veterans in the start-up spectrum and have years of experience in guiding emerging businesses to reach their maximum potential.

Questions for Sanjeev Aggarwal:

1. How was your experience of writing From Pony to Unicorn?

Educational, as I was able to reflect on my learnings.

2. In what ways would you say that the start-up ecosystem in India has changed in the past ten years?

The level of founder ambition has reached a new high.

3. Which factor, according to you, works most efficiently in helping a start-up scale sustainably?

Navigating inflection points with thought.

4. Which sector in the start-up domain remains the least explored? Why do you think that’s the case?

Agri-tech! The market is large and highly intermediated.

5. As book publishers, we cannot help but ask you about your favourite books that you’d like to recommend to our readers?

How Will You Measure Your Life by Clayton Christensen

Questions for T.N. Hari

1. What propelled you to pen From Pony to Unicorn?

Sanjeev and I have been through the scale journey multiple times and have seen several small startups go on to become large companies from very close quarters. The urge to share our learning and insights with the next generation of entrepreneurs who are trying to build sustainable businesses was what motivated us to write this book.

2. Which is your most favourite section of the book?

‘The Human Capital’ section is my personal favourite for the simple reason that this is a topic close to my heart.

3. What kind of books do you enjoy reading? Are there any that you’d like to recommend to our readers?

I don’t particularly read too many management books. Six best books I read in 2020 are as follows:

- Where will Man Take Us? by Atul Jalan (Atul writes better than Harari and Kurzweil put together)

- Indica – A deep natural history of the Indian subcontinent by Pranay Lal

- The Liberation of Sita by Volga

- The Palace of Illusions by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

- Fermat’s Last Theorem by Simon Singh)

- Shackleton’s Way by Margot Morrell and Stephanie Capparell

4. If you could describe the current start-up ecosystem in India in one word, what would it be and why?

Vibrant

5. According to you, which is the one skill that an HR professional must necessarily possess?

A deep understanding of human psychology.