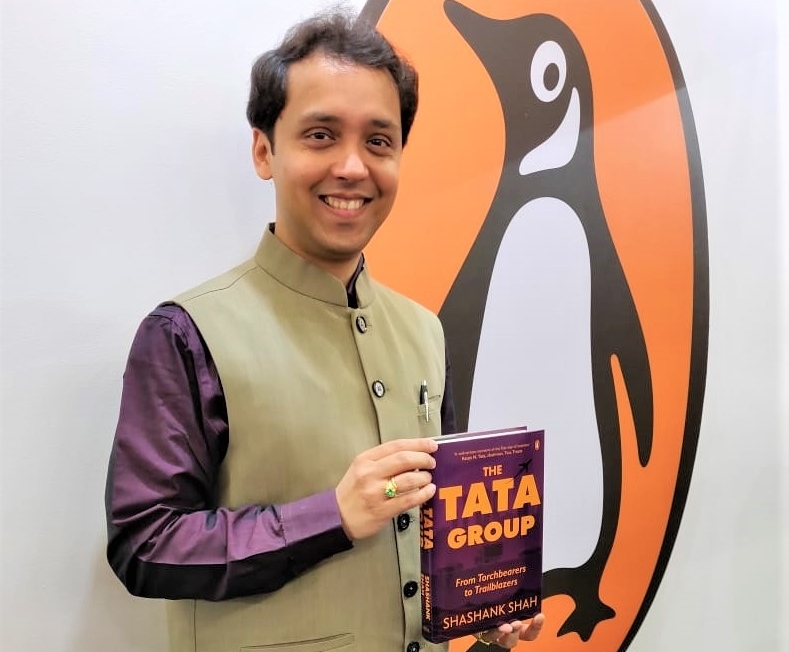

Shashank Shah is a thought leader in the fields of stakeholder-centric business strategy, corporate responsibility and sustainability. He has been a visiting scholar at Harvard Business School; and is currently the editor-in-chief of the Harvard University Postdoctoral Editors Association; and consulting editor with the Business India Group. His first book Win Win Corporations was published in 2016.

Read on to know more about his new book The Tata Group, as we catch up with him on a conversation.

According to you, how has Tata group maintained its leadership position over the years? What are the main factors of its successful performance?

How many companies in India can boast of celebrating 15 decades of existence? Very few. Moreover, how many of those have consistently ranked at the top of the charts for their financial and indeed all-round performance? Tatas have remained India’s numero uno corporate for 80+ years, ever since corporate rankings have been measured in India. Contextually, let us compare two among the tallest business leaders of the 19th century – Jamsetji Tata and Premchand Roychand (the former worked under the latter in his formative years) and their institutions a century later. While Premchand Roychand & Sons (under the fourth generation) recorded a turnover of ₹82.3 crores in March 2014, Tatas had a turnover of ₹650,000 crore. It can be said that the successors of Jamsetji Tata fulfilled their commitment to sustain and achieve the dream of India’s industrialisation, the seeds of which he had sown in his lifetime in substantial measure. Two key aspects contributed the most in ensuring that the Tata flame shines brighter by the day. These are the founder’s vision and the Tata model of business.

Firstly, let’s talk about their model of business. The Tata companies are commonly referred to as the Tata Group. There are approximately 100 Tata companies of which 29 are publicly listed and the remaining 71 are privately held by Tata Sons, which is the main holding company. Tata Sons ownership in Tata companies varies from 20 to 70%. The elected chairman of the Tata Sons board is recognized as the Tata Group chairman. In 2018, about 66% of the equity capital of Tata Sons was held by 15 philanthropic trusts endowed by various members of the Tata family over many generations. The Tata Trusts are legally mandated to annually spend 85% of their dividend earnings on social welfare projects. Thus, the Tata model of business is a virtuous cycle of wealth creation and not just profit making. The wealth thus created from the society, is ploughed back into the society, thereby completing a virtuous loop – a rarity in contemporary capitalist society.

Second is the vision of the founder who made the society the core stakeholder of the Tata businesses and not the Tata family or the shareholders. In my interactions with the senior-most executives of the Tata Group, I observed a conviction that the ultimate objective of the Group is to contribute to societal well-being through the Tata Trusts. If this wealth is generated by harming/negatively impacting any of the stakeholders during the process of wealth creation, and then distributed as charity, it defeats the vision of the founding father who said 120 years ago, ‘In a free enterprise, the community is not just another stakeholder in business, but is in fact the very purpose of its existence.’

Thus, the vision and its execution has been done with a far-greater passion for creating wealth through entrepreneurship. Albeit, the focus has not been on profit-making alone, but on investing in core sectors vital to nation building, venturing into businesses involving long gestation periods, taking risks to go global, focusing on customer affection and employee wellbeing, investing financial and human resources to change with a changing world and integrating business excellence and innovation into the core approaches of doing business. Lastly, despite these efforts, if a Tata company isn’t successful in retaining a slot among the top three in that industry category, exit the business and divert investment and energy in newer and more promising areas.

These, I believe have been the building blocks of the Tata success story.

What motivated you to author this monumental work?

You have used the right word – monumental. 180,000 words and 1,500 end-notes make my book an almost encyclopaedic work on the Tata Group, which is without a parallel. When you study a conglomerate like the Tata Group, you aren’t just studying a company; you are studying 100 companies from 20+ industries operating in three distinct time periods – the British Raj, the post-independence period and the post-liberalisation era. To add to that is also the business-bureaucracy angle from the years of Jawaharlal Nehru to Narendra Modi. So it is indeed a monumental task!

However, the world of Tatas has always fascinated the researcher in me. Not only do they serve every industry—from the seas to the skies (as depicted on the cover page of my book), but also, for fifteen decades, their leadership and management philosophy have balanced the commercial and social imperatives of business. They have distinguished themselves through priorities and processes by evolving and practising an approach that can be referred to as the ‘Tata way of business’, which effectively combines international best practices with Indian values, and blends the capitalist spirit with socialist primacies.

At a time when the world is undergoing serious problems—environmental, social, financial and emotional—corporations, which have been one of the most potent forms of collective effort towards the achievement of focused objectives, can play a major role in contributing to solutions through products, services, processes and practices. In contemporary times, corporations have the opportunity to transition from purely economic and profits-focused entities to those prioritizing value creation for several stakeholders. In the Tata story, I have found a strong resonance to the approach I subscribe to—where profits and social well-being can coexist; where profits are not at the expense of the society, but profits benefit society; where profits are not an end in themselves, but the means to a more noble end.

This book is the third in a series of my research work that explores stakeholder-centric corporate strategies in India Inc. There couldn’t have been a better conglomerate than the Tatas to study this. Moreover, the last major book on the Tata Group ‘Creation of Wealth’ was published by RM Lala in 1992. In the subsequent 25 years, the revenue of the Group has increased 25 times from ₹24,000 crores to ₹650,000 crores of which 67% now comes from outside India. This story had to be told. Hence, I embarked on this ‘monumental work’.

In the book, the reader will find out what makes the Taj one of Asia’s largest group of hotels; why did the Corus acquisition not meet expectation and yet how does Tata Steel rank among the top 10 ten steel-makers in the world; how did Tata Power envision and deliver clean energy a century before that term first become popular; how could Tata Chemicals become the world’s third-largest producer of soda ash; how did Tata Motors turnaround Jaguar Land Rover when even the Ford Motor Company failed to do so and also rank among the world’s top 10 ten commercial vehicle manufacturers; how did Tata Global Beverages beat global competition and emerge as the world’s second-largest tea company; and how come TCS, which was on the verge of being wound-up in 1978 went on to become not only India’s most valued company at $100-billion but also the second largest IT services company in the world. These are some of the most fascinating stories that have been narrated in an engaging manner such that even a lay reader can understand.

Could you share with our readers a few iconic path breaking findings of the Tata Group that you discovered while working on this book?

I think the greatest path breaking finding has been their financial success story, which is rarely discussed. People believe that Tatas are a good company, but are doubtful of their wealth creation capabilities for their shareholders? Tatas spending ₹2,000 crores every year through their Trusts and CSR investments, and their contribution in the establishment of some of the finest educational, health and cultural institutions don’t impress hard-nosed capitalists. To explore whether Tatas have done well by being good or not, I embarked on a comparison of Tata Group with leading Indian business houses and global conglomerates on the benefits shareholders received by investing in Tata companies. The analysis revealed some eye-opening numbers.

A simple review of shareholder returns across Tata Group showed that over a 26-year horizon (1 April 1992 to 31 March 2018), the Group outperformed the market and other well-known conglomerates in India and abroad. This was particularly important given that the companies analysed had lasted various economic, business and political cycles while they continued to be leaders in their sectors. Given Tatas’ diversity, we identified 16 businesses that best represented the Group’s presence across most sectors and decided to equally divide an investment of ₹100,000 in these businesses. The 16 companies included: Tata Steel, Tata Motors, TCS, Indian Hotels, Tata Power, Tata Chemicals, Tata Communication, Tata Elxsi, Tata Metaliks, Tata Sponge Iron, Tata Investment Corporation, Tata Global Beverages, Titan Company, Trent, Voltas and Rallis. By 2018, the invested ₹100,000 would be worth roughly ₹40-lakhs, nearly quadrupling the same investment in benchmark indices. During the same period, a BSE Sensex investment would be worth ₹10.26 lakhs and the Nifty would be worth ₹10.73 lakhs.

While India witnessed several notable conglomerates over the years that have benefitted shareholders, the Tata Group stood ahead of comparable size companies post-liberalisation. An investment of ₹100,000 in January 2009 equally across the selected Tata companies would be worth ₹998,200 (10x the initial investment) in March 2018. The same would be worth almost 5x and 2.5x in the case of Aditya Birla Group and Reliance Group respectively. The Tata Group also outperformed developed market peers in Asia, America and Europe. Annualized total shareholder returns over a 26-year period from 1 April 1992 to 31 March 2018 for Mitsubishi (Japan) were 5.2%, GE (USA) were 5.9%, Siemens (Germany) were 10%, Berkshire Hathaway were 14.2% and the Tata Group were 15.2%.

These findings have amazed even Tata insiders who haven’t attempted such a study. I haven’t come across such analyses in any other publication on the Tata Group. I believe this is one of the greatest contributions of my work.

Any interesting anecdotes that you came across while working on this book?

Let me share three – one from the post-liberalisation era, one during the License Raj and another during the British Raj. Through each of them, you will see a common thread of Tata-ness in decision making.When Tata Tea decided to exit from the plantation business in 2000s, and transition to the branded tea and retail business, it wasn’t willing to exit its plantations before a sustainable model of livelihood was chalked out for its plantation workers. For this, Tata Tea had three strategic options. One was an outright sale to another company. This was the option selected by its competitor—Hindustan Unilever (HUL). McLeod Russel India, the world’s largest tea producer, had picked up HUL’s seven tea estates in Assam. Given that Tata Tea’s plantation earnings were in red, the new company would most likely slash wages, shut down social welfare programmes and even relieve thousands of employees. So, Tata Tea decided against it. The second option was to close the plantations. This would again lead to loss of livelihoods for over 13,000 employees working on those plantations, some of whom were third-generation workers. The company ventured for the third option, which involved divesting control to its workforce. It was a first-of-its-kind experiment in the world, at least in the tea plantation business.

Given that plantation workers were no longer Tata employees, but its suppliers, a prudent decision would have been to absolve itself from investments in existing employee welfare programmes. Over the years, Tata Tea had invested substantial amounts in providing health and education facilities to its plantation employees. Logically, with the formation of a new company, the responsibility of managing these should have been transferred to the new management as the quantum of annual investment was nearly ₹20-crores – not a meagre sum. This included a 150-bed secondary care general hospital, a school for employees’ children, and four vocational institutes for workers’ children with disabilities. When this matter was discussed with the then vice chairman of the company, his answer was, ‘Continue, whatever it takes.’ And so Tata Tea continued to spend ₹20-crores every year on the social welfare projects of a company that was now its supplier!

In the late-1980s, Taj Hotels had suspended two employees on charges of theft. Post an enquiry process, the charges were upheld, and their services terminated. They made several appeals, one of which was to J.R.D. Tata, the Tata Group Chairman. On the morning of the day he completed 50 years as chairman of Taj, J.R.D. spent an hour reading the enquiry proceedings and questioning the main witness. He told the concerned Taj manager, ‘I am satisfied that you have been fair. Go ahead and terminate them, but please see if we can do something for their families, especially if they have school going children.’ The octogenarian J.R.D. did not want the kids to suffer because of their fathers’ follies.

In 1922, Tata Steel was on the verge of closure as its profits plummeted thanks to the British Raj’s antithetical reciprocation to Tatas’ magnanimity. The Tatas had supported the British Raj during World War I by fulfilling war-related product requirements instead of more profitable commercial products. However, in the post-war years, the Raj opened up the market leading to low-cost steel dumping from Europe and Asia severely affecting Tata Steel’s profitability. Some investors suggested that Tata Steel be sold off. ‘Over my dead body’, thundered R.D. Tata (father of J.R.D. and one of the four founders of Tata Sons). To salvage his father’s dream and the Tatas’ flagship company, Sir Dorabji Tata (Jamsetji’s son) pledged his personal wealth of ₹1 crore, including his wife’s jewellery and the Jubilee Diamond (twice the size of the Koh-i-noor), and raised a loan from the Imperial Bank of India (now State Bank of India) to pay salaries and remain afloat. This is contrasting to contemporary times when corporate leaders secure pay-rises for themselves when their companies are bailed out through governmental support and tax payers’ munificence – both in India and especially overseas (during the financial crisis of 2008). The likes of Nirav Modi and Vijay Mallya who enjoy luxurious lives while their employees pay a heavy price for their failed businesses have a lot to learn from the Tata way of business. It isn’t limited to the case of Tata Steel in 1922, Jamsetji did the same for the Swadeshi Mills in 1880s and Ratan Tata for Tata Finance in 1990s and Tata Teleservices in 2017.

How intense was the research process for this book?

I have always believed that business books – whether in the genre of trade books or research books, need to be grounded in reality and not just based on individual opinions. In recent times, a lot of opinionated books pass for books on business, management and leadership. I believe, the job of business authors is to provide the readers with several perspectives on the core issue of study, explore and share insights from the existing body of knowledge and finally complement them with the author’s observations. This rigour is rarely seen in contemporary writing. Probably, for that reason, we see authors churning out books almost every year.

I have followed the approach I have just recommended for this book, and even for my previous book, which was also published by Penguin – ‘Win-Win Corporations’. The research and writing process has been very intense. It started a decade ago, when I first started interviewing Tata leaders for my doctoral research in the area of Corporate Stakeholders Management. It continued as I pursued my postdoctoral research on Leadership. By then I had already interviewed nearly 50 Tata leaders across group companies. During my postdoctoral research, I discovered that an opportunity existed to capture the contemporary Tata story through a book. Over the next five years, I interacted with 50 senior leaders and in 2018 began the process of writing the book. I visited Tata factories and offices in Mumbai, Bangalore, Pune and Jamshedpur. I visited Tata Central Archives in Pune, which are a repository of rare and unpublished documents dating back nearly 100 years. The Tata Steel Archives in Jamshedpur were an equally useful treasure of unknown facts and material going back to early 1900s.

As a trained management researcher, I reviewed national and international publications – journals, magazines and newspapers from India and overseas, especially USA and UK, where the Tata Group has a substantial presence. Another interesting fact is that The Tata Group is the most studied conglomerate at global business schools. I referred to nearly 100 case studies on various Tata Group companies published by Harvard, Stanford, INSEAD, Darden, IIMs and several other leading business school publishing houses. For quantitative analysis, I accessed rare statistics and trends on the performance of Tata companies form the 1940s to the current times. You will find in the book analysis of the kind that isn’t available even with the Tata Group themselves. In my recent interactions, some of the Tata insiders confided that they will be using my analysis in many of their presentations! Such interest and appreciation makes my research a very fulfilling exercise.

I believe the book has the rigour of another doctoral research project. It isn’t a hagiography. The Tatas have their share of mistakes, misjudgements and missed opportunities, which have been elaborated by me. The book has triangulated perspectives and presented successes, failures, learnings and implementable approaches on India’s largest conglomerate. And all this, in a very readable and simple story-like style. I believe the real success of writing a simple business book is when your homemaker mother or grandmother can enjoy reading it. That’s ‘The Tata Group’ book for you!

The Tata Group decodes the Tata way of business, making it an exceptional blend of a business biography and management classic.