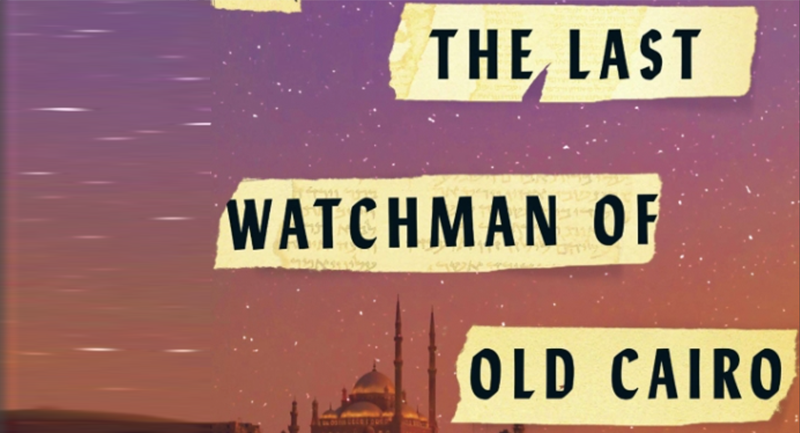

The Last Watchman of Old Cairo is a moving page-turner of a novel from acclaimed storyteller Michael David Lukas. This tightly woven multigenerational tale illuminates the tensions that have torn communities apart and the unlikely forces—potent magic, forbidden love—that boldly attempt to bridge that divide.

Here is an excerpt!

One Sunday toward the end of fifth grade, my father asked me whether I wanted to spend the summer with him in Egypt. He and my mother had already worked out all the details. I would stay with him in Cairo for two months, then come back to Santa Fe a few weeks before school began.

Of all the days that summer, the one that stuck with me most was the afternoon my father took me, Uncle Hassan, and a couple of distant male cousins on a felucca ride down the Nile.

It was a bright blue-and-white day. There was a soft breeze blowing upriver and the windows of the skyscrapers along the water glinted with reflected sunlight. I was sitting with my father at the back of the boat while Uncle Hassan and my cousins manned the front. We sailed up the Nile for an hour or so; then the captain dropped anchor near the bottom tip of Zamalek and everyone stripped down to their underwear and jumped in. They beckoned for me to join, but in spite of my father’s assurances, I didn’t trust the water. It looked like the kind of river—thick with silt the color of coffee ice cream—where you might find leeches and piranhas or, at the very least, those slimy little fish that ate the dead skin off your feet.

“No, thank you,” I said in Arabic and leaned back against the side of the boat in an effort to convey my comfort.

After a few minutes of splashing around, Uncle Hassan pulled himself back into the boat. I remember he smiled and made as if to light a cigarette. Then, with a violent lurch, he wrapped his arms around my chest and threw me into the Nile. The abruptness of it knocked the wind out of me and when I came up, sputtering and coughing, trying to tread water in wet shoes and jeans, everyone was laughing. My cousins sang a humorous song in my honor and I tried to laugh along with them, even though I knew I was the butt of the joke.

Back in the boat, I took off my wet clothes and set them out to dry. There were angry tears welling up at the corners of my eyes, but I held them back, knowing from experience that crying only made things worse. I was mad at Uncle Hassan. But most of all, I blamed my father, for allowing it to happen, for not protecting me, and for chuckling to himself as he draped the towel over my shoulders. To his credit, he didn’t say anything once he saw that I was upset. He didn’t try to explain himself or apologize. He just sat there with me at the back of the boat, watching the murky brown water pass a few feet below us.

“There is a proverb,” he said eventually. “ ‘Drink from the Nile and you will always return. Swim in it and you will never leave.’ ”

Then he leaned over the edge of the boat and cupped out a handful of water.

“This is our blood,” he went on, trickling the water onto my knee. “Nearly a thousand years our family has lived on the Nile. This river is in our veins.”

He lit a cigarette and we were both quiet for a long while.

“We are watchers,” he said, throwing the half-smoked butt into the Nile. When I didn’t respond, he explained. “Our name, al-Raqb, it means ‘the watcher,’ ‘he who watches.’ ”

“ ‘He who watches,’ ” I repeated, and he smiled.

“It is the forty-third name of God.”

He thought for a moment, shading his eyes against the sun; then he asked me the same question he asked every Sunday night.

“Would you like to hear a story?”

“Yes,” I said, and he began.

“Once there was a boy named Ali—”

I must have heard that story a dozen times before. But that particular afternoon—watching the city unfold from its haze—it felt more immediate, more real. This river a few feet below us was the same river that had flowed through the city a thousand years earlier, when Ali al-Raqb first took up the position of watchman, the same river that had flooded the valley every spring for hundreds of years.

“We protect the synagogue,” my father said when the story finished, “and we guard its secrets.”

“Secrets?” I asked.

He shifted in his seat and, glancing back over his shoulder, dropped his voice slightly, so no one else on the boat could hear what he was saying.

In one corner of the courtyard, he told me, there was a well that marked the place where the baby Moses was taken from the Nile. Beneath the paving stones of the main entrance was a storeroom filled with relics, including a plank from Noah’s Ark. And hidden in the attic, behind a secret panel, was the greatest secret of all, the Ezra Scroll.

He leaned in, so close that I could feel his breath on my face.

More than two thousand years ago, he said, during the time of the prophets, there lived a fiery scribe named Ezra who took it upon himself to produce a perfect Torah scroll, without flaw or innovation. He worked on the scroll for many years and when he was finished, he presented it to the entire community. The people assembled outside the walls of Jerusalem. And when Ezra opened the scroll, they all stood, for they knew that this was the one true version of God’s word. It was the perfect book, the perfect incarnation of God’s name, and it glowed with a magic that could heal the sick, enlighten the perplexed, or bring back the spirits of the dead.

“Have you seen it?” I asked. “Is it real?”

My father lit a new cigarette and stared into the water, as if he might find his story there.

“That’s enough for today,” he said, eventually, and I knew not to press any further.

For the rest of the ride, as we sailed back toward the 26th of July Bridge, I sat with my father at the back of the boat, looking out on the water and thinking about the heroic history of our family, about the Ezra Scroll and the generations of watchmen who protected it.

For much of my childhood, my last name—al-Raqb—had felt like a burden. I hated the questions it inspired, the taunts, and the well-meaning adults wondering where a name like that came from. I dreaded the moment when, without fail, substitute teachers would pause and glance up from the attendance sheet, apologizing in advance for their mispronunciation. It even looked strange—al-Raqb—the hyphen in the middle, the lowercase “a,” and that unpronounceable double consonant at the end. In third grade, prompted by a particularly embarrassing incident with a new teacher, I had waged a semi-protracted and nearly successful campaign to change my last name to Shemarya, like my mom, or Levy, like Bill. But that afternoon on the Nile, I wouldn’t have traded al-Raqb for anything.

I was a watcher, I told myself. He who watches.

Get a copy of The Last Watchman of Old Cairo!