Ravinder Singh is the bestselling author of several books such as I Too Had A Love Story, Can Love Happen Twice, Your Dreams Are Mine Now and This Love That Feels Right.

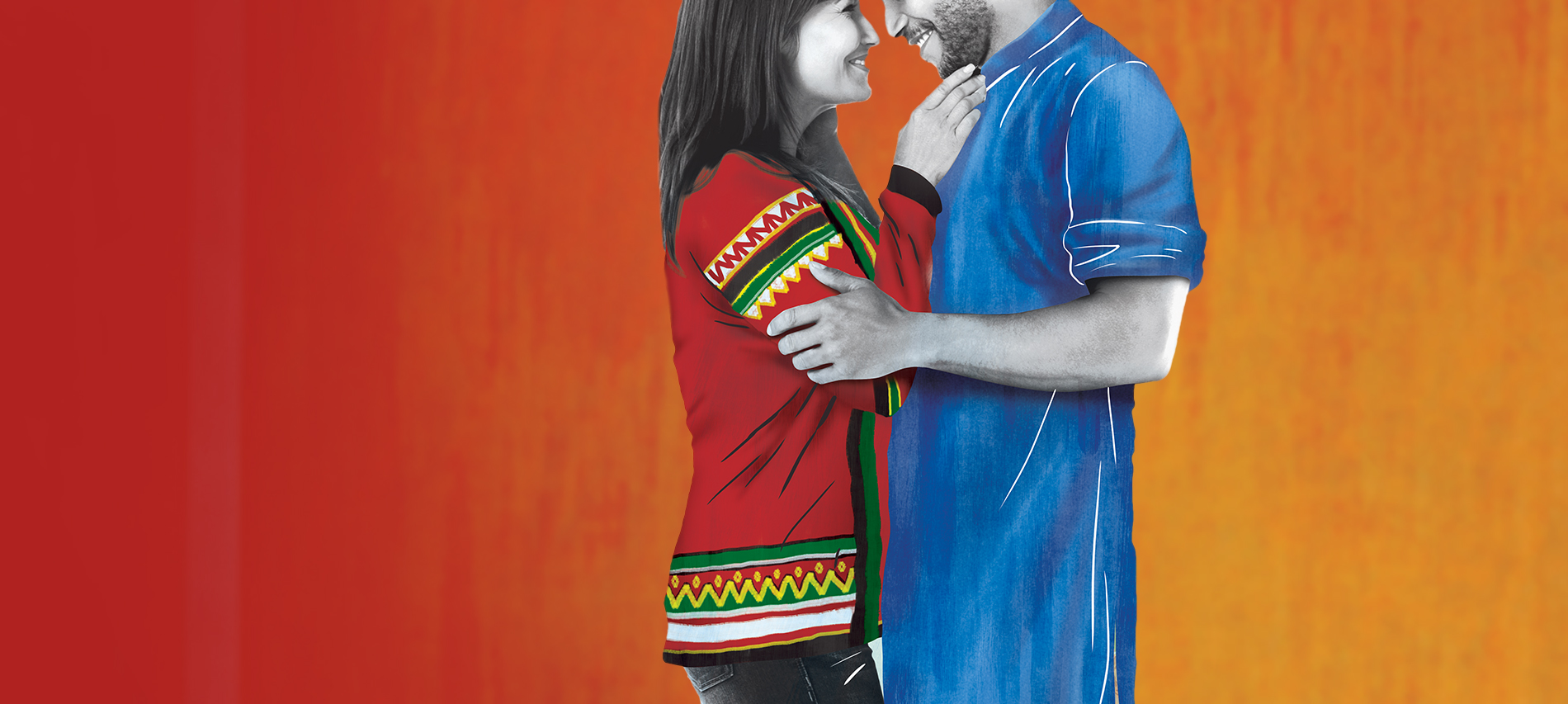

Singh’s latest novel, Will You Still Love Me is about Lavanya Gogoi, from the scenic hills of Shillong and Rajveer Saini who belongs to the shahi city of Patiala. Worlds apart from one another, the two land up next to each other on a flight from Mumbai to Chandigarh. It’s love at first flight, at least for one of them. It is a deeply moving story showcasing love at its worst and its best.

Here are eight quotes from the book- Will You Still Love Me that will break your heart:

Category: Features

articles features main category

Writing We That Are Young by Preti Taneja

Preti Taneja was born and grew up in the UK. She teaches writing in prisons and universities, and has worked with youth charities and in conflict and post conflict zones on minority and cultural rights. She is the co-founder of ERA Films, and of Visual Verse, the anthology of art and words. We That Are Young is her debut novel. It has been longlisted for the Desmond Elliot Prize and the Jhalak Prize, and shortlisted for the Republic of Consciousness Prize.

————————————

I arrived in New Delhi in January 2012, carrying my battered copy of Shakespeare’s King Lear and 300 A4 pages of double spaced text: the first drafts of Jivan and Gargi, and half of the Radha sections of something called We That Are Young. The writing wasn’t wonderful, I remember feeling that. It was hard to capture the different voices of my characters from London. I worked a lot in my local library. I felt like a ‘writer’ there, or at least, one in training. But I wasn’t really convincing myself on the page. Shakespeare’s language and plot were a magnetic puzzle – I wanted to work with them but not give in to them. The book had to stand on its own terms.

We That Are Young was never going to be a realist novel if it was to cleave to an epic play that is set in a no-place, a no-time. I wanted the book to be a dark carnival, hyper-real, with a polyphonic structure and modernist sensibility in the lines. India as a setting can handle elements of the real and the mythological, the psychoanalytical tradition of the West and a circular sense of time in ways other settings can’t. Yes, I had high hopes – but working from books and memory in England, it read like the first draft it clearly was.

The stakes were high: I had lost my mother to cancer when I was 28. I cared for her, for almost eight years with my family, till she died. What should I do with the inheritance she left me? It included courage, an example of sacrifice and risk-taking, as well as the security she had worked all her life to leave me. Two years after, I had got a job I loved, reporting on minority rights abuses for an NGO. I had the chance to travel and met people who trusted me with their stories. All of us sharply aware of the gulf between those who have freedom of movement, freedom of speech and those who do not, and the responsibilities that brings. I had a regular sandwich and coffee order in a nearby café. I commuted against the tide of city bankers streaming out of Liverpool Street station. Then I turned 30, and I still wasn’t doing the thing I had said I wanted to do all my life. Write fiction. I knew something had to change.

I enrolled on a night-class on the far side of the city, reached via the stopping Circle Line, East to West. I got a portfolio of stories together, and applied for a part-time Master’s in Creative Writing, which I could study for around my job. Two years later, I got my degree. I knew I wanted to carry on teaching and writing. I handed in my notice at work. The next day the email came: I had won full funding for a PhD. To work on We That Are Young.

Four months in, and that same instinct to jump made me pack up my life. I found a place to rent in Delhi via endless online searches, and paid the deposit without actually seeing it first. Then I told my Delhi family and friends that I was coming to write a book based on Shakespeare, set in India and was going to live in a rental for as long as I could afford it. ‘Whatever,’ they said. ‘Just come.’

I rediscovered my second city, the place I’ve been coming to since I was a child, on new terms. There was a fermenting energy; there was creativity; there was so much rage. There were important books I could not get in the UK about Indian politics, men’s fashion, women’s rights. I kept notebooks – there ended up being 15 in total – and made daily cuttings from national newspapers and magazines. Journalistic training learned crossing borders and working in different parts of the world and (in an early, misguided incarnation) as a very junior financial reporter now got me into the back kitchens of hotels, expensive parties, the outskirts of the city. Everyone wanted to tell me about what was wrong with India. Corruption, inequality, misogyny, ‘tradition,’ pollution, caste, expansion, city planning, waste, child abuse, the building of the metro, politics, safety. There was also a forward momentum among certain classes and in the media: long held injustices were being highlighted; new possibilities for equality were being claimed. So many people I met were working, had been working for years for this.

I would write every day. The rest of Radha, all of Jeet and most of Sita was drafted as the heat became brighter. Against family advice I travelled to Goa in April. I got sick from the humidity and had to come back early. And then, finally I went to Srinagar. A person I will never be able to thank enough, took me, silent and wrapped in shawls, into parts of the city he said that even most Srinagar people don’t go to. He introduced me to artisans, traders, chefs who talked to me about their work, and their daily routines, their hopes for their children. I stopped writing and just listened. I celebrated my 35th birthday with my partner on a houseboat overlooking the Dal: the stay was a gift from my godmother, my mother’s dearest friend.

I don’t believe writers think about their own process – how, when, what with – until they are asked to. For me, there were some simple imperatives. I was 35. I had taken a pay cut and tried to make a career change. I had to finish the book, get it published, and from that, apply for teaching jobs, perhaps write the next thing – that was the plan. Finishing became a kind of obsession, driven by the PhD submission deadline, funding running out, the need to sell the novel and seek paid work. With the 15 notebooks, press cuttings and a stack of other people’s novels and non-fiction from across India and the diaspora, I returned to my childhood home in June 2012. One more house move, and I finished the first full draft of my manuscript by December. Then my agent sent it out and I submitted my PhD.

I got the PhD. But, We That Are Young found no favour with London or Delhi publishing. The editors said, ‘ambitious,’ ‘clever,’ ‘brilliant idea’ and ‘powerful.’ There was, ‘too close to the bone’ and variations on, ‘Shakespeare? Really?’ Everyone, I mean, everyone said, ‘no.’

I could still research and teach, I thought. I could try for an academic career, if fiction was not to be. I began to focus on that. But writing We That Are Young was like being possessed by five crazy characters: they would not leave me alone. I had to keep working on the book. I believed that the India I had seen, and the way people told me it was changing, the way the world was changing, had to be expressed in fiction, now, and I still wanted to try to do it. When I started the novel, there was no Trump, no Brexit. It was the dog days of Congress in India. It was before a brutal rape on a Delhi bus became world news. But anyone really looking could see what was coming. The rise of the right-wing in different parts of the world. Wave after wave of protests against corruption, war, and for social justice were taking place. There was Rhodes Must Fall, and calls for the decolonisation of public spaces and curricula. People were documenting it via film and non-fiction. Some fiction writers were also getting through.

When I finally sold the fourth complete draft of my manuscript to the UK independent publisher Galley Beggar Press, it was January 2016.

There’s a lot more to this story, including the people close to me, who wouldn’t let me give up on my endless editing. One round of which was done on a rainy holiday in Wales, where I sat in my Tshirt, with my laptop in the hotel bath, pulling an all-nighter while my long-suffering partner slept next door. That was the version before Galley Beggar said yes. Then there was even more editing, intricate line stuff – it was thrilling but exhausting for all of us, and it went to the wire – it was finished just 10 days before the book actually became a real object in a warehouse, waiting to go out.

Writing is hard, editing is hard. It all feels less like creation, more like excavation. I often read as I write – returning to find segments of non-fiction that feed my stories, or fragments of poetry and other peoples’ writing – the kind that makes me work even harder at my own. We That Are Young is now in the bookshops and online, on people’s shelves and TBR piles, maybe in their bathrooms or beach bags. In India, its beautiful Penguin Random House hand-painted cover suggests water, hair, mehndi, bloodlines. My five crazy characters are partying without me – I saw them in the airport bookshop in Kolkata, in Delhi, Jaipur, in Bangalore; people send me pictures of them in Glasgow, Oxford, Norwich and Mumbai. They are talked about on YouTube and in blogs, just as they are in the world of the book. It’s meta. As Radha might say.

We That Are Young ends with a beginning, placing whatever might come next in the reader’s hands. Since I finished it, real world events, some positive – the #metoo and #TimesUp campaigns, the steps towards decriminalising gay sex (again), ongoing protests against child rape; some horrific – including those headline cases of sexual violence, water running out in cities, toxic smog, the rise of the religious right and its fascist ideology, go on: ‘machinations, hollowness, treachery, and all ruinous disorders…’ as Gloucester puts it, in King Lear.

Meanwhile, I am meant to be working on the next thing. I don’t know much about that, but I know the process won’t change. It will start with reading. It always has.

—————-

Author Portrait: Rory O’Bryen

—————–

In Conversation with Kim Wagner – The Author of The Skull of Alum Bheg

In his latest book, The Skull of Alum Bheg, author Kim Wagner explores the mutiny of 1857 and the shadows of colonial rule in India. Spurred by an intriguing find, Wagner’s elegant narrative uses the story of one man’s death and skull to excavate the underbelly of Britain’s nineteenth century empire.

Here’s an exclusive interview with Kim A. Wagner, where the author shares his opinion on British Imperialism and what inspired him to write the book – The Skull of Alum Bheg.

_______________________________________________________________________

1. What was your inspiration behind writing The Skull of Alum Bheg?

My starting point was obviously the story of the skull itself, as outlined in the brief note that had been found inside of it back in 1963. But in trying to write about the events of the Indian Uprising from the perspective of a single – and in many ways an insignificant – individual, I was very much inspired by the classics of micro-history and especially the work of the likes of Carlo Ginzburg and Natalie Zemon Davis. The challenge I was facing was the fact that while I had the remains of Alum Bheg, I never ‘found’ him in the historical records, and so I had to write the book by tracing an outline of this individual, trying to reconstruct the world he inhabited and the people who surrounded him. The subtitle is obviously a nod to Gautam Bhadra’s classic essay, ‘Four Rebels of 1857’, first published in Subaltern Studies IV in 1985.

2. Tell us something about your writing process.

For this book, I wrote what I thought of as different ‘layers’ or different ‘voices’, in sequence, and only at the end did I put them together into one complete text. So I wrote the narrative of the Scottish and American missionaries first, then that of Alum Bheg and the sepoys, and finally the background and analysis. It was a very different way of writing from what I am used to, and you only know whether the plan you have in your head actually works once you put it all together right at the end. I am also not very economic with words – for every 10.000 words that I write, I will have produced three times that in the form of notes and drafts of paragraphs in varying stages. It is a time-consuming and cumbersome process, which leaves my computer littered with orphan files, but it works for me.

3. What was the most intriguing facet of colonial India you came across while researching for your book?

When you take a micro-historical approach, the grand narratives come apart at the seams and you begin seeing new and intriguing details. It was interesting to look at the Indian Uprising in a place like Punjab, where the sepoys of the Bengal Army were invaders as much as the British were. When the outbreak eventually did happen at Sialkot, where Alum Bheg’s regiment was stationed, it was accordingly a very different type of mutiny, compared to, for instance, Meerut or Delhi, where most of the local population joined the sepoys. It was also fascinating to see how local dynamics shaped the violence, and personal grievances and relationships played a large role during the chaos of the outbreak. I’ve never been able to adequately explain why some Indian servants would lay down their lives for the sahibs and memsahibs, while others readily stabbed them in the back. Sometimes new insights also mean new questions to be answered.

4. Victorians’ had a fetish for collecting and exhibiting body parts. Are there some other such instances you can share with us?

I have previously worked on the collecting of skulls of so-called ‘Thugs’ by phrenologists in the 1830s, but that was just the beginning of a veritable obsession with skulls. In the final chapter of the book, I describe some of the later examples from the British Empire: Following the Battle of Omdurman in 1898, for instance, General Kitchener had the body of the Mahdi disinterred and the skull was kept, which later caused a scandal. The same happened in South Africa where the heads of tribal leaders, such as Luka Jantje or Bambhata, were cut off and either used for identification or kept as private souvenirs. It is often assumed that there was a clear-cut distinction between the ‘rational’ collection of scientific specimens and the ‘irrational’ taking of war-trophies – in practice, however, such distinctions are often unsustainable

5. Finally, if in a line you had to summarize British imperialism in India, how would you do that?

Despite the conventional narrative of cultural expertise and liberal governance, British rule in India was defined by a lack of comprehension concerning local grievances and anti-colonial sentiments, and as a result prone to panic and the use of exemplary violence.

Fifty Shades Darker, An Excerpt

Determined to win Anastasia back, he tries to suppress his darkest desires and his need for complete control, and to love Ana on her own terms. Read E L James book, Fifty Shades Darker to dive deeper and darker on their love story,

Here’s an excerpt.

————————

Get a grip, Grey.

I damp down my fear and make a plea. “You look like you’ve lost at least five pounds, possibly more since then. Please eat, Anastasia.” I’m helpless. What else can I say?

She sits still, lost in her own thoughts, staring straight ahead, and I have time to study her profile. She’s as elfin and sweet and as beautiful as I remember. I want to reach out and stroke her cheek. Feel how soft her skin is…check that she’s real. I turn my body toward her, itching to touch her.

“How are you?” I ask, because I want to hear her voice.

“If I told you I was fine, I’d be lying.”

Damn. I’m right. She’s been suffering—and it’s all my fault. But her words give me a modicum of hope. Perhaps she’s missed me. Maybe? Encouraged, I cling to that thought. “Me, too. I miss you.” I reach for her hand because I can’t live another minute without touching her. Her hand feels small and ice-cold engulfed in the warmth of mine.

“Christian. I—” She stops, her voice cracking, but she doesn’t pull her hand from mine.

“Ana, please. We need to talk.”

“Christian. I…please. I’ve cried so much,” she whispers, and her words, and the sight of her fighting back tears, pierce what’s left of my heart.

“Oh, baby, no.” I tug her hand and before she can protest I lift her into my lap, circling her with my arms.

Oh, the feel of her.

“I’ve missed you so much, Anastasia.” She’s too light, too fragile, and I want to shout in frustration, but instead I bury my nose in her hair, overwhelmed by her intoxicating scent. It’s reminiscent of happier times: An orchard in the fall. Laughter at home. Bright eyes, full of humor and mischief…and desire. My sweet, sweet Ana.

Mine.

At first, she’s stiff with resistance, but after a beat she relaxes against me, her head resting on my shoulder. Emboldened, I take a risk and, closing my eyes, I kiss her hair. She doesn’t struggle out of my hold, and it’s a relief. I’ve yearned for this woman. But I must be careful. I don’t want her to bolt again. I hold her, enjoying the feel of her in my arms and this simple moment of tranquility.

But it’s a brief interlude—Taylor reaches the Seattle downtown helipad in record time.

“Come.” With reluctance, I lift her off my lap. “We’re here.”

Perplexed eyes search mine.

“Helipad—on the top of this building.” How did she think we were getting to Portland? It would take at least three hours to drive. Taylor opens her door and I climb out on my side.

“I should give you back your handkerchief,” she says to Taylor with a coy smile.

“Keep it, Miss Steele, with my best wishes.”

What the hell is going on between them?

Dangerous Minds by Hussain Zaidi and Brijesh Singh – An Excerpt

Dangerous Minds delves into the complex and intricate lives of some of the most talked-about terrorists of the country. What drove them to such violent designs? What were their compulsions? Can a human being be so ruthless and heartless, and why?

Hussain Zaidi and Brijesh Singh explore the lives, early beginnings, careers and sudden transformations of such persons into merchants of death in this book.

——–

The police had managed to arrest the accused, but the mastermind Nasir was still at large. The entire city police force was hunting for the absconding Nasir. On 12 September, a police team received a tip-off that he was likely to visit Dadar with an aide. The unverifiable story that was later narrated was that Nasir came in a blue Maruti 800 along with an aide. The police officers claim they asked him to surrender and, like all criminals who are destined to be killed in an encounter, Nasir refused to pay heed to the warnings. According to a press release, the police were left with no choice and opened fire on the accused. Nasir and his aide were fatally injured. At KEM Hospital, both were declared dead on arrival.

That left Zahid Patni. Savdhe had been making the rounds of his Mira Road residence, asking the family to persuade the son to return and cooperate in the investigation. It was not clear whether it were the police’s threats of implicating the entire family in the case or Zahid’s own conscience, but he did return to the city. Evidence recorded in the Mumbai POTA court stated that Zahid began to feel guilty after he saw the massacre at Gateway and Zaveri Bazaar. He had not anticipated so much bloodshed. Restless, he went to the local Masjid in Dubai and confessed his crime to a priest by the name of Mufti Jaafar Sahab. The priest told him it was a sin to kill innocent people. An apparently remorseful Zahid then decided to surrender to the Mumbai Police. He returned on 1 October.

Zahid decided to turn into an approver and testify against the others.

The Mumbai Police’s investigation of the twin blasts failed to answer some important questions. For instance, how could Nasir procure such a massive quantity of explosives so easily? How, despite working in Dubai along with Hanif and Zahid, was he an expert bomb-maker? If Nasir was based in Mumbai and his family was in Hyderabad, why have they remained untraceable? In fact Nasir was too much of a conundrum for the investigators. Ultimately, Zahid’s interrogation and subsequent investigations threw light on hitherto fuzzy details.

Nasir was actually a top confidant of the notorious terrorist Riyaz Bhatkal. Together, they had formed a large network of terrorists and volunteers in the country. It was secretly called the ‘R-N Gang’, R for Riyaz and N for Nasir. The duo had formulated the preposterous formula of committing robberies to fund bombings. They justified the act of robbery, considered a cardinal sin necessitating the amputation of hands according to sharia law, by terming it Maal-e-Ghanimat (the spoils of war), thus making robbery booty eligible for utilization in jihad. Nasir’s actual name was Abdur Rehman and he had told Zahid that he had been to Pakistan frequently, where he was trained in making bombs and explosives. Nasir had also shown him a credit card from Citibank Pakistan and also his various covers that he used for his multiple identities.

It was through Dubai-based Pakistanis that Zahid was exhorted to join the Lashkar-e-Taiba in August 2000 after which he was introduced to Nasir. The conspiracy meetings were held among Pakistanis and Indians like Nasir, Hanif and Zahid. The Pakistanis who were members of Lashkar urged them not to live in Dubai but to move back to India and spread terror through bomb blasts.

Judge M.R. Puranik, who presided over the trials for over six years, finally passed a judgement in the case on 6 August 2009. He observed: ‘. . . not awarding death penalty to accused no 1, 2 and 3 will be mockery of justice . . . they did not do the acts out of emotional outburst but their act was well-planned and pre-designed . . . they have shown total disregard for human lives by enjoying the act of killing innocent persons.’

About Fahmida, Judge Puranik noted, ‘. . . participation of accused no. 3 [Fahmida] in causing the bomb blast was not the result of her helplessness on account of dominance of her husband but it was her well-designed action with free will. Since the accused persons are bloodthirsty, therefore there is no scope for their reformation and rehabilitation.’

‘They shall be hanged by the neck till they are dead.’

As required by law, the trial court referred the matter to the Bombay High Court for confirmation of the death penalty. Three years after the conviction by the trial court, on 10 February 2012, the Bombay High Court upheld the verdict on all counts.

A Girl Like That by Tanaz Bhathena – An Excerpt

Tanaz Bhathena was born in India and raised in Saudi Arabia and Canada. She is the author of A Girl Like That and The Beauty of the Moment (forthcoming in 2019). Her short stories have appeared in various journals including Blackbird, Witness and Room. Tanaz’s debut novel, A Girl Like That, reveals a rich and wonderful new world to readers. It tackles complicated issues of race, identity, class and religion and paints a portrait of teenage ambition, rebellion and alienation that feels both inventive and universal.

Let’s read an excerpt from the book, A Girl Like That.

———–

By the time I was sixteen, however, it was boys like Abdullah who would help me skip school, who offered me their own cigarettes and smoked with me in their cars, parked in a deserted lot by the Corniche on Thursday afternoons.

Only Abdullah became a lot more than a guy I simply went out with for cigarettes or food— and that became evident when he kissed me on our third date— a light, pleasing dance of lips and tongues that made me forget for a few moments that we were in a public place.

“What’s the matter?” he asked when I pushed him away.

“I thought you liked me.”

I laughed, gently tracing his frown away with a finger.

“I do like you. But maybe we should not keep doing this here.”

I gestured toward the railing in the distance, where a lone man stood, staring at the sunlight glittering on the waves.

Abdullah rolled his eyes. “He’s so far, Zarin. He’s not even turned this way.”

“And when he does turn, we’re going to be the ones in trouble. I’m not taking any chances.”

“Come on.” Abdullah was grinning. “You’re telling me you’ve never done this before?”

“It may surprise you to know that I haven’t,” I said truthfully.

As reckless as I was under most circumstances, I did not want to kiss every guy I went out with on these dates. Half the guys I’d gone out with had been far too worried about the religious police showing up to catch us red- handed, while the other half had been far too intimidated by me and never attempted more than a timid kiss on the hand or the cheek.

Abdullah was an exception in many ways. For one: I genuinely enjoyed his company. He was intelligent. He made me laugh. And he smelled nice too. Which was why, when he leaned in to kiss me, I let him.

There were times when we talked when Abdullah would mention Farhan’s name. “Rizvi and I did this,” or “Rizvi and I did that,” or “Rizvi’s such a loser sometimes, I don’t even know why I’m friends with him.” I listened closely to these little stories— bits and pieces of information about a boy I had only, as of yet, seen in pictures or from a distance during school functions. Those were the nights I would imagine Rizvi’s lips on mine instead of Abdullah’s— a wisp of curiosity that fluttered through my brain when I was falling asleep— a thought I managed to squash before it bloomed into heat. I instantly felt guilty afterward, sometimes even refusing to go out with Abdullah when he texted me a week later, making an excuse of a doctor’s appointment or a test.

The beauty about Abdullah was that he never followed up on my lies or asked additional questions. Cool. Next week then, he always wrote back in reply. It was almost as if he expected me to have a part of myself that I kept private the way he kept parts of his own life a mystery, evading any questions that might have anything to do with his family or childhood.

“Some things are too messed up to explain,” he said, and I agreed.

It made perfect sense for us to be together; to meet up each Thursday to talk, smoke, and sometimes kiss; to lose ourselves in random conversations about school or movies or music for an hour and forget who we really were.

————

Mother Earth, Sister Seed: 5 Facts De-mystifying the Old Ways

Lathika George is a writer, landscape designer, environmentalist and organic gardener. She has published articles on food, design, travel, gardening and the environment in InsideOutside, Architectural Digest, Food 52, Condé Nast Traveler, The Hindu’s BLink. In Mother Earth, Sister Seed, she looks at India’s traditional agricultural communities and the changes-some good, some not-that good, modernization and urbanization have wrought.

Here are a few facts from the book de-mystifying the old ways.

————————–

Author Nanditha Krishna on the close relationship between Hinduism and Nature

There is a close symbiotic relationship between Hinduism and Nature. The basis of Hindu culture is dharma or righteousness, incorporating duty, cosmic law and justice. Every person must act for the general welfare of the earth, humanity, all creation and all aspects of life. Dharma is meant for the well-being of all living creatures. The verses of the Vedas express a deep sense of communion of man with god. Nature is a friend, revered as a mother, obeyed as a father and nurtured as a beloved child. In Vedic literature, all of nature was, in some way, divine, part of an indivisible life force uniting the world of humans, animals and plants.

Five thousand years ago, the Vedic sages showed a clear appreciation of the natural world and its ecology. There is a hymn to the rivers (Nadistuti Sukta) in the Rig Veda and a hymn to the earth (Prithvi Sukta) in the Atharva Veda. Throughout the Vedas there is a deep respect for life which is an important manifestation and expression of the gods. The need to protect and conserve biological diversity is exemplified in the representation of Shiva, Parvati, their two sons Karttikeya and Ganesha and their vahanas or vehicles – bull, lion, peacock and mouse respectively – who live in close harmony.

There is a very strong and intimate relationship between the biophysical ecosystem and economic institutions which are held together by cultural relations. Hinduism has a definite code of environmental ethics and humans may not consider themselves above nature, nor can they claim to rule over other forms of life. Every aspect of nature is sacred for the Indic religions: forests and groves, gardens, rivers and other waterbodies, plants and seeds, animals, mountains and pilgrimage centres. The sacred is still visible in modern India. All creation is a manifestation of the divine with no dichotomy between humanity and divinity. Religious practices are influenced by local environmental and festivals coincide with a natural phenomenon.

I fell in love with sacred groves attached to Hindu temples, where not a twig may be broken and which are the remnants of ancient forests where sages lived in harmony with nature; with rivers that gush from the hills and meander through the land; with the sacred tanks attached to each temple, the sacred plants and the animals respected by my religion; with the awe-inspiring mountains which reach up to the skies and where the Gods live. Every festival reminds us of the importance of nature in our lives. As the author of Sacred Plants of India and Sacred Animals of India I explored the divine relationship between human beings, plants and animals, which are an essential part of every Hindu prayer.

“The Earth is my mother and I am her child,” says the hymn to the Earth in the Atharva Veda. The human ability to merge with nature was the measure of cultural evolution. Hinduism believes that the earth and all life forms – human, animal and plant – are a part of Divinity, each dependant on the other for sustenance and survival. All of nature must be treated with reverence and respect. If the forests, clean water and fresh air disappear, so will all life as we know it on earth.

——————————————————

A historian, environmentalist and writer based in Chennai, Nanditha Krishna has a PhD in Ancient Indian Culture from Bombay University. She has been a professor and research guide for the PhD programme of C.P.R. Institute of Indological Research, affiliated to the University of Madras. Her latest book, Hinduism and Nature delves into the religion’s deep respect for all life forms, the forests and trees, rivers and lakes, animals and mountains, which are all manifestations of divinity.

Will You Still Love Me, An Excerpt

Ravinder Singh is the bestselling author of I Too Had a Love Story, Can Love Happen Twice?, Like It Happened Yesterday, Your Dreams Are Mine Now and This Love That Feels Right . His new book, Will You Still Love Me is deeply moving, disturbingly close to reality, and love at its worst and its best.

Here’s an excerpt.

_______________________

Rajveer sat down on his seat and looked at her with newfound feelings. The spectacle of a sleeping beauty kindled a variety of emotions in his heart. Now that he could look at her without feeling self-conscious, Rajveer realized how attractive a woman Lavanya was! His eyes rested on the glowing skin of her face and her neck before they slid down to her waist, to the skin visible between the blouse and the long skirt she wore. He watched the rhythmic rise and fall of her chest as she slept. The tiny sleeves of her blouse clung to her elegantly shaped arms.

Rajveer took in the details of her beauty—her jet-black silky hair that lay softly on her shoulders, her not so long fingers that ended in shapely nails. She possessed a well-toned body many women only craved for. Lavanya wasn’t tall, yet her average frame possessed more than enough charm to be considered quite striking.

Then suddenly she turned her head in her sleep. It made Rajveer immediately retract his gaze. He thanked god that she hadn’t abruptly opened her eyes and caught him staring at her. He then looked around self-consciously to check if anybody else had noticed him doing so. He was safe, he realized.

To distract himself, Rajveer pulled out the Hello 6E from the seat pocket in front of him and began flipping through it. He occasionally checked on Lavanya too, who remained deep in sleep.

More than half an hour passed this way. By then, Rajveer had also pulled out his laptop from his luggage and had begun working on it. Just then he heard the captain’s voice letting passengers know that he had initiated the descent of the plane. This woke up Lavanya from her sleep.

‘Slept well?’ Rajveer asked. There was a sense of familiarity as he spoke and a certain softness.

She rubbed her palms over her face and then looked at him, ‘Yes. I feel so fresh now!’ She smiled.

Then reacting to the announcement that the use of lavatories was not allowed as they had begun descent, Lavanya quickly unbuckled her seat belt. She wanted to use the loo as soon as possible.

Caught by surprise, Rajveer had to quickly close his laptop, place the in-flight magazine on the middle seat, close the tray table, and then unbuckle himself, all in a rush. Lavanya didn’t have much time. She tried to manoeuvre through the narrow space between Rajveer’s legs and the seat in front. In the process, Rajveer’s knees rubbed against her skirt. Her touch and proximity felt like a jolt of electricity to him. Briefly he found himself staring straight at her bare, slender waist. Gosh! How much he wanted to feel that dewy skin on the tips of his fingers. He got a whiff of her perfume and he inadvertently took in a deep breath.

‘Sorry,’ Lavanya apologized for the discomfort to Rajveer. You are welcome, he said in his mind.

Sujata Massey Like You Never Knew Her

Mystery author Sujata Massey’s new book, A Murder on Malabar Hill, is based in 1921 Bombay. It is about a young, intrepid and intelligent girl with a tumultuous past, who joins her father’s prestigious law firm to become one of India’s first female lawyers.

The author holds a BA in Writing Seminars from John Hopkins University and started her working life as a features reporter for the Baltimore Evening Sun.

Here are six things you didn’t know about the author.

____