Like the real fools and jesters of the time, Shakespearean fools were common individuals that outwitted people of higher social status. They find place in many of William Shakespeare’s works:

“Shakespeare’s fools are subtle teachers, reality instructors one might say, who often come close to playing the part that Socrates, himself an inspired clown, played on the streets of Athens. They tickle, coax and cajole their supposed betters into truth, or something akin to it. They take the spirit of April Fools’ Day to an inspired zenith.” (Edmundson, 2000)

This April Fool’s day, here’s our literary take on the Shakespeare’s fools:

—————————-

——————————-

Edmundson, M. (2000). Playing the Fool. New York Times, Retrieved from www.nytimes.com.

https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/00/04/02/bookend/bookend.html

Category: Features

articles features main category

5 Tips on Work Life Balance From A Techie-Turned-Farmer

Disheartened by his stressful life in the city, Venkat Iyer decided to quit his job at IBM and take up organic farming at his Dahanu farm. He soon went from wielding microchips to sowing moong dal. But this transition wasn’t easy. With no experience in agriculture, his journey was wrapped around uncertainty. Iyer’s debut novel, Moong over Microchips follows his extraordinary experience battling erratic weather conditions and stubborn farm animals to stumbling upon a world of fresh air, organic food and sheer joy.

Here are five tips from Iyer’s book that will help you achieve the perfect work- life balance:

Tip one: Make use of liberal leave policy

Tip two: The 5 Cs

Tip three: You should know when gadgets need to be turned off

Tip four: True wealth is in being happy, healthy and content with what one has

Tip five: Wellness is based on these five parameters

A Dash of Poetry from Some of the Finest Indian Poets

Immensely admired for the sensitivity with which they portray human emotions and with a popularity that since decades has remained at an all-time high, this World Poetry Day we present to you a poem from some of these finest Indian poets. Their voice will tug at the heart of every poetry lover.

Let’s have a look at these fantastic voices.

———————-

——————–

5 sure-shot mantras to attain happiness; The Dalai Lama shows the way

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama is the spiritual leader of Tibetan people. In 1989, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his non-violent struggle for the liberation of Tibet. In Happiness, the Dalai Lama opens a window into the attainment of absolute happiness in day to day life.

Let’s look at these 5 poignant quotes from Happiness, where the Dalai Lama shows us the way to attain happiness.

—————

A Flair to Carve Ingenious Characters; Who Else but Philip Roth

Philip Roth is the author of 31 books and has won the Pulitzer Prize, the International Man Booker Prize and many other literary awards, making him arguably America’s greatest living writer. The characters carved by this stellar author, have always invited a wide audience and been a subject of interest.

In this blog piece we celebrate this genius’ birthday through 5 of his characters.

——————————-

1. Lucy Nelson, When She Was Good

2. Alexander Portnoy, Portnoy’s Complaint

3. Peter Tamopol, My Life as a Man

3. Peter Tamopol, My Life as a Man

4. Libby Herz, Letting Go

4. Libby Herz, Letting Go

5. David Kepesh, The Breast

5. David Kepesh, The Breast

———————————–

———————————–

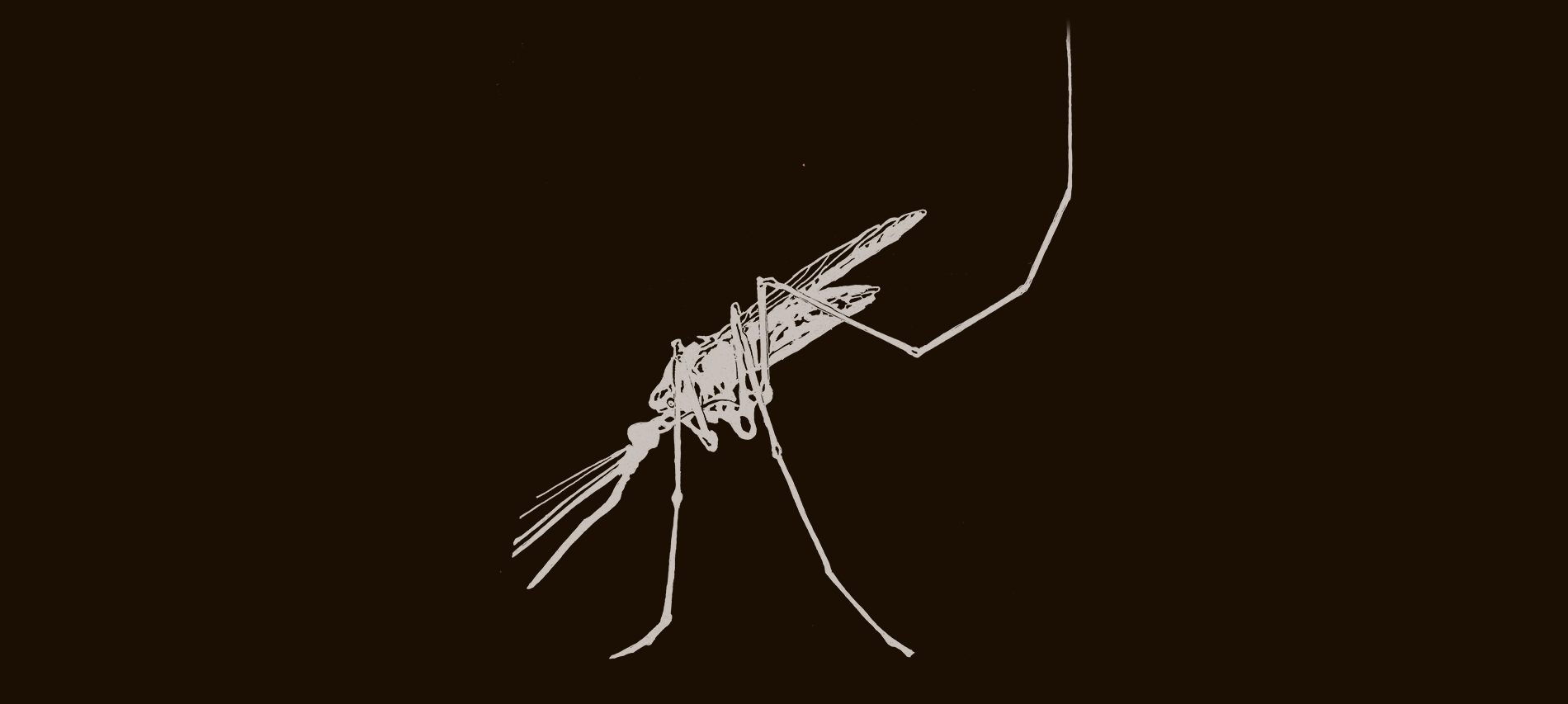

The Fever by Sonia Shah – An Excerpt

Humans have suffered from mosquito-borne diseases for more than 500,000 years. Not only do they still plague us, but they have also become more lethal. In The Fever, journalist Sonia Shah sets out to address this concern, delivering a timely, inquisitive chronicle of malaria and its influence on human lives. In her book, she mentions the delayed study of a drop of blood that lead to the discovery of the microbe responsible for malaria.

Here is an excerpt from her book about the accidental discovery of the microbe.

—————–

One day in the late 1870s, two pathologists, Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli and Edwin Klebs, collected air and mud samples from the Roman Campagna. From the samples, they isolated ten-micro millimeter-long rods, which from the vantage point of their crude microscopes, seemed to develop into long threads. When injected into lab rabbits, the long threads soon had the bunnies heaving with chills and fever. Inside their slaughtered bodies, the pathologists found the ten-micro millimeter-long rods, once again.

The two scientists decided that they’d found the microbe responsible for malaria. It was a germ, it lived in the soil and the air, and they called it Bacillus malariae. They announced their findings in 1879.

The scientific method is not infallible, of course, and such mistakes are made, even when the entire economy of a newly formed nation depends on the results.

Counterevidence soon emerged.

In November 1880, Alphonse Laveran, a French surgeon stationed in Constantine, Algeria, peered at a crimson blob on a glass slide. How he found what he did is a bit of a mystery. Most nineteenth century microscopists soaked their slides in chemicals, their cutting-edge techniques thus unknowingly kill ing the malaria parasites in their samples and rendering them all but invisible amid the scattered debris of the magnified blood. Those who did examine blood from malaria victims while still fresh, as Laveran did, presumably did so more promptly than he did on this particular day. The blood was still warm when Laveran excused himself from its notice. What precisely he did upon abandoning his slide nobody knows, but whatever it was, it took about fifteen minutes. Maybe it was a cup of coffee.

In any case, during the lull, the drop of malarial blood on the glass cooled. The change in temperature roused the parasites in the sample, which now considered that they had left the warm-blooded human for the cool environs of a mosquito body. Male forms of the parasite would soon be called upon to fertilize female ones, and each started to sprout long flagella and wave them about, in lascivious preparation. Laveran returned to his microscope expecting yet another static scene. Instead, the shocked surgeon caught sight of tiny spheres propelling themselves with fine, transparent filaments, wrigglingly alive.

——————

7 Astounding facts about Gandhi from this critical-edition of An Autobiography

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi is among the most enigmatic, charismatic, deeply revered and equally reviled figures of the twentieth century. His Autobiography, one of the most widely read and translated Indian books of all time, is a classic that allows us to glimpse the transformation of a well-meaning lawyer into a Satyagrahi and an ashramite. In this first-ever Critical Edition, written by the eminent scholar, Tridip Suhrud shines new light on Gandhi’s life and thought. The deeply researched notes elucidate the contexts and characters of the Autobiography, while the alternative translations capture the flavour, cadence and quirkiness of the Gujarati.

Let’s have a look at some of the facts from this critical version that you may not have known:

————-

————————-

De-mystifying Auroville in 7 Facts

Auroville has a reputation as a cosmopolitan, spiritual township, but it remains an enigma to outside observers. This anthology of writing from the community, edited by a long-time resident, Akash Kapur, and representing forty-odd authors from around the world, seeks to shed light not only on Auroville’s ideals but also on its lived reality.

Here are seven facts about Auroville that you should know about:

———-

6 Times Ramnath Goenka Championed the Cause of Journalism

B.G. Verghese (1927-2014) served with the Times of India for many years before becoming the information adviser to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. His book, Warrior of the Fourth Estate: Ramnath Goenka of the Express, is a roller-coaster ride through the twists and turns of Ramnath Goenka’s fortunes, including scandals and scoops, fiery public campaigns, dramatic court battles and the making and unmaking of political leaders and governments. Along the way, it tells the story, too, of a newspaper.

Let’s get to know about those 6 times when Ramnath Goenka championed the cause of journalism.

———-

————

————

12 Rules For Life by Jordan B. Peterson – An Excerpt

Jordan B. Peterson is a professor of psychology at the University of Toronto. Formerly a professor at Harvard University, he was nominated for its prestigious Levenson Teaching Prize. In this book, 12 Rules For Life: An Antidote to Chaos, he combines ancient wisdom with decades of experience to provide twelve profound and challenging principles for how to live a meaningful life, from setting your house in order before criticising others to comparing yourself to who you were yesterday, not someone else today.

Let’s read an excerpt from this fascinating book.

———–

RULES? MORE RULES? REALLY? Isn’t life complicated enough, restricting enough, without abstract rules that don’t take our unique, individual situations into account? And given that our brains are plastic, and all develop differently based on our life experiences, why even expect that a few rules might be helpful to us all?

People don’t clamour for rules, even in the Bible . . . as when Moses comes down the mountain, after a long absence, bearing the tablets inscribed with ten commandments, and finds the Children of Israel in revelry. They’d been Pharaoh’s slaves and subject to his tyrannical regulations for four hundred years, and after that Moses subjected them to the harsh desert wilderness for another forty years, to purify them of their slavishness. Now, free at last, they are unbridled, and have lost all control as they dance wildly around an idol, a golden calf, displaying all manner of corporeal corruption.

“I’ve got some good news . . . and I’ve got some bad news,” the lawgiver yells to them. “Which do you want first?”

“The good news!” the hedonists reply.

“I got Him from fifteen commandments down to ten!”

“Hallelujah!” cries the unruly crowd. “And the bad?”

“Adultery is still in.”

So rules there will be—but, please, not too many. We are ambivalent about rules, even when we know they are good for us. If we are spirited souls, if we have character, rules seem restrictive, an affront to our sense of agency and our pride in working out our own lives. Why should we be judged according to another’s rule?

And judged we are. After all, God didn’t give Moses “The Ten Suggestions,” he gave Commandments; and if I’m a free agent, my first reaction to a command might just be that nobody, not even God, tells me what to do, even if it’s good for me. But the story of the golden calf also reminds us that without rules we quickly become slaves to our passions—and there’s nothing freeing about that.

And the story suggests something more: unchaperoned, and left to our own untutored judgment, we are quick to aim low and worship qualities that are beneath us—in this case, an artificial animal that brings out our own animal instincts in a completely unregulated way. The old Hebrew story makes it clear how the ancients felt about our prospects for civilized behaviour in the absence of rules that seek to elevate our gaze and raise our standards.

One neat thing about the Bible story is that it doesn’t simply list its rules, as lawyers or legislators or administrators might; it embeds them in a dramatic tale that illustrates why we need them, thereby making them easier to understand. Similarly, in this book Professor Peterson doesn’t just propose his twelve rules, he tells stories, too, bringing to bear his knowledge of many fields as he illustrates and explains why the best rules do not ultimately restrict us but instead facilitate our goals and make for fuller, freer lives…

Order is where the people around you act according to well understood social norms, and remain predictable and cooperative. It’s the world of social structure, explored territory, and familiarity. The state of Order is typically portrayed, symbolically—imaginatively—as masculine. It’s the Wise King and the Tyrant, forever bound together, as society is simultaneously structure and oppression.

Chaos, by contrast, is where—or when—something unexpected happens. Chaos emerges, in trivial form, when you tell a joke at a party with people you think you know and a silent and embarrassing chill falls over the gathering. Chaos is what emerges more catastrophically when you suddenly find yourself without employment, or are betrayed by a lover. As the antithesis of symbolically masculine order, it’s presented imaginatively as feminine. It’s the new and unpredictable suddenly emerging in the midst of the commonplace familiar. It’s Creation and Destruction, the source of new things and the destination of the dead (as nature, as opposed to culture, is simultaneously birth and demise).

Order and chaos are the yang and yin of the famous Taoist symbol: two serpents, head to tail.* Order is the white, masculine serpent; Chaos, its black, feminine counterpart. The black dot in the white— and the white in the black—indicate the possibility of transformation: just when things seem secure, the unknown can loom, unexpectedly and large. Conversely, just when everything seems lost, new order can emerge from catastrophe and chaos.

For the Taoists, meaning is to be found on the border between the ever-entwined pair. To walk that border is to stay on the path of life, the divine Way.

And that’s much better than happiness.

————-