In 1963, a human skull was discovered in a pub in Kent in south-east England. The skull is a troublesome relic of both anti-colonial violence and the brutality and spectacle of British retribution.The Skull of Alum Bheg: The Life and Death of a Rebel of 1857 offers a critical assessment of British imperialism that speaks to contemporary debates about the legacies of Empire and the myth of the ‘Mutiny’.

Here’s an excerpt.

——————

As a havildar, Alum Bheg received a pay of 14 rupees per month, double that of ordinary sepoys, and this had been the rate for more than half a century, even as the prices of commodities increased over time.After 16 and 20 years’ service, sepoys would receive an extra bonus of one or two rupees per month, which according to one Indian officer, made a big difference: ‘A prudent sepoy lives upon two, or at utmost three rupees a month in seasons of moderate plenty; and sends all the rest to his family. A great number of the sipahees of our regiment live upon the increase of two rupees, and send all their former seven to their families.’ A substantial part of their salaries were indeed sent back to the sepoys’ villages, as Sleeman explained: ‘They never take their wives or children with them to their regiments, or to the places where their regiments are stationed. They leave them with their fathers or elder brothers, and enjoy their society only when they return on furlough. Three-fourths of their incomes are sent home to provide for their comfort and subsistence, and to embellish that home in which they hope to spend the winter of their days.’

The close link to a particular region and the ties between the sepoys and the villages, was an outcome of the unique recruitment practices of the Bengal Army as they had developed over the past century. As the East India Company became increasingly involved in politics during the second half of the eighteenth century, the nature of British rule in India gradually assumed all the trappings of a sovereign power. The Company was thus transformed from primarily a trading venture to a colonial state in its own right, which by 1818 derived most of its income from land revenue rather than trade. In order to maintain and expand its territorial possessions, the Company depended on local Indian soldiers led and trained by British officers along European military principles. At the time, however, the British were still an emerging power and had to compete with both Indian and European rivals, who were also offering similar service to local soldiers. Before the advent of the ‘civilising’ impulse, much of the Company’s legitimacy as a state power was, in fact, derived through the continuation of pre-colonial practices, which included the establishment of an army of high-caste Hindu sepoys. Out of sheer necessity, the Company in Bengal thus tapped into the military labour market of northern India and relied on existing networks of patronage and caste-ties to recruit peasant regiments directly from the zamindars or landholders of Awadh and Bihar. Accommodating high-caste usages and practices within its regiments was an effective means by which the East India Company could become an attractive and legitimate military employer in India during this period. The Company thus managed to establish a loyal base of recruitment by employing the rhetoric of high-caste status as well as the promise of regular pay and pension. The British recruited directly from the villages of Awadh and Bihar, and when sepoys returned from furlough, they would bring younger family members back to their regiment as prospective recruits. This dynamic reinforced the links between the regiment and the village and meant that parts of the Bengal Army functioned as a sort of extended kinship network. The end-result was a uniquely homogeneous body of sepoys in the Bengal Army, composed mainly of high-caste Brahmins, Bhumihars, and Rajputs.

The religious identity and social status of Alum Bheg and his fellow sepoys, however, did not simply pre-date colonial rule or reflect Indian traditions that were then merely adopted within the Bengal Army—the social status of the sepoy was itself a product of service within that army. A number of the religious and social identities linked to military service, the status of which was taken more or less for granted by 1857, had actually only emerged during the preceding century and were thus ‘invented’ traditions rather than timeless castes. The decline of the Mughal Empire had caused significant political and social turmoil, but it had also enabled groups such as the Rajputs and Bhumihars, or so-called agricultural Brahmins, of eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, to establish a high-caste status through military service. This entailed a combination of the warrior ideal with the ritual purity and social privilege of Brahmins, and the observance of strict dietary rules associated with priestly Hinduism. At the same time, the indigenous military labour market was becoming increasingly constricted as the British, with the help of the sepoys expanded their sphere of influence. By 1818, the Company had established an effective monopoly of power on the subcontinent, having defeated or pacified most rival Indian states that would otherwise have provided employment for thousands of Indian troops. The Bengal Army, which constituted the military force throughout the newly ceded and conquered territories in north India, provided the perfect frame within which the reinvented high-caste military traditions of the Bhumihars and Rajputs could be formally institutionalised. It presented the sepoys with the opportunity to improve and secure their new-found status and by endorsing and encouraging the high-caste status of the sepoys, the British were better able to control their troops and ensure continued support from the local landowners in the regions that supplied recruits.

————

Category: Features

articles features main category

5 Star-crossed Couples From Literature Who Make Us Believe in Love

Literature has given us some iconic couples who have enthralled us with their story and made us believe that in the end love conquers all. They also show us how love can be found in the unlikeliest of places.

In this blog post, we cherish five of them.

———————-

1. Jay and Daisy – The Great Gatsby

2. Sarah and Charles – The French Lieutenant’s Woman

2. Sarah and Charles – The French Lieutenant’s Woman

3. Florentino and Fermina – Love in the Time of Cholera

3. Florentino and Fermina – Love in the Time of Cholera  4. Anna Karenina and Count Vronsky from Anna Karenina

4. Anna Karenina and Count Vronsky from Anna Karenina

5. Lady Chatterley and Oliver from Lady Chatterley’s Lover

5. Lady Chatterley and Oliver from Lady Chatterley’s Lover

—————-

—————-

Memories of Fire by Ashok Chopra – An Excerpt

Author of the bestselling Of Love and Other Sorrows and A Scrapbook of Memories: My Life with the Rich, the Famous and the Scandalous, Ashok Chopra is the chief executive of Hay House Publishers India. His latest book, Memories of Fire, is the compelling story of five childhood friends who meet after a gap of fifty-four years. They embark on a journey into the past, laden with nostalgia and humour, and encompassing all the ugly and wonderful things life has to offer.

Here’s an excerpt from this gripping tale.

——————————————

God’s gift to Deepak was a phenomenal memory. Anything he ever read he could easily recall and quote. Every student and every teacher admired and envied him. They all predicted he would grow up to be a writer and achieve sure fame internationally. ‘He is a rare student . . . Mark my words, Deepak is going to be more than just a professor of literature . . . He will be much more,’ Brother Walsh would tell his colleagues in the staffroom. ‘He will lecture at Oxford!’ This was then the ultimate ambition of every teacher.

‘No, he will grow up to be a very famous and celebrated writer of global acclaim!’ some of the others predicted. How wrong they all were!

Deepak remained a brilliant mind—a genius some would say—but became just a simple professor of literature at the university. Besides an article or two, he only ever wrote letters—to poets, novelists and playwrights; he also wrote regularly to editors of newspapers; only a few of these were published in the ‘letters to the editor’ columns, and that too in truncated versions; most were ignored and junked. Deepak would get most upset if an author quoted incorrectly or translated poorly. He would immediately write to the publication with his copious corrections listed in detail. Over the years, he was in regular correspondence with the eminent writer-historian and the country’s most-read and much-respected columnist Khushwant Singh, whose column ‘With Malice Towards One and All’ was published in over two dozen newspapers and magazines across India and Pakistan. Deepak would point out to the writer his errors, check his translations and cite his misquotations. Normally, Singh would agree with everything sent in and offer his thanks for the same. But once, perhaps in a foul mood, he wrote back to Deepak one line on a postcard: ‘I disagree with you.’ Deepak, who hardly ever got angry, lost his cool and responded equally angrily: ‘Of course you have the right to disagree. Just as Evelyn Beatrice Hall stated in her work The Friends of Voltaire: “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it”—a statement often misattributed to Voltaire himself. But at least propound your reasons for the said disagreement. To say simply: I disagree with you is, to my understanding and knowledge, not enough. What’s the logic? What’s the ratiocination? What’s the sound judgement and chain of thought or coherence, connection or authority behind your disagreement? I fail to understand.’

Finally, Khushwant agreed that Deepak was right and he wrong. Later he wrote about Deepak in his columns and paid him a rich, and well-deserved, compliment: ‘Deepak is a rare being . . . He must be the most erudite man in the country . . . a human encyclopedia. There is just about nothing he doesn’t know . . .’ Most unassuming and totally unambitious, Deepak became a professor in the English department of the university. The position entitled him to a spacious bungalow on its sprawling campus and the headship of the department in rotation. He rejected both. In his private life, he did have a few affairs but they all ended in disaster simply because the women couldn’t discuss poetry, fiction, drama or even history with him. Thereafter, he came to the conclusion that women were a sheer waste of time and would provide various examples from world history and literature to prove his point. Each one was valid. He remained a bachelor. How he met his biological needs no one knew!

—————-

Dreamers by Snigdha Poonam – An Excerpt

Snigdha Poonam is a journalist based in New Delhi. She currently reports on national affairs at the Hindustan Times. She won the 2017, ‘Journalist of Change’ award of Bournemouth University for a work of reportage that appeared on Huffington Post. Her first book, Dreamers: How Young Indians Are Changing Their World, talks about a generation that cannot – will not – be defined on anything but their own terms. They are wealth-chasers, attention-seekers, power-trappers, fame-hunters. They are the dreamers.

Here’s an excerpt from this powerful book.

——————————————-

It might be any other editorial meeting, in any of a million new clickbait start-ups: a set of editors huddled around a table to discuss what news and gossip to feed their audience next. The process is quick and brutal. Ideas are thrown around like bids on a trading floor.

Why your best friend is your true love, just like Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher.

This is what you need to know about Amanda—Justin Bieber’s new girlfriend.

How your face would look if you survived a car crash.

Fifteen times Donald Trump was trolled hilariously.

Fifteen minutes is all it takes the team to go over the whole range of American obsessions, from Kardashians to belly fat, from sex confessions to life hacks; and fifteen seconds is the average time they spend making a decision. Poor Amanda is peremptorily ditched for Victoria Beckham, who has just kicked up a parenting scandal by posting a photo on Instagram in which she is kissing one of her children. The editors opt for a bold stand, and argue the former Spice Girl did nothing wrong. Or, as the published article will later put it, ‘This is why kissing your kids on the lips is not a bad idea.’ They have a reason for choosing the story: ‘Child kissing is trending in the US,’ a young woman wearing black eyeshadow informs the room. The car crash idea is tweaked to imagine the impact of two car crashes on someone’s face at once. Everyone agrees it should only be a visual story. Americans, apparently, simply adore accident horror. Kim Kardashian loses out to Kylie Jenner. Another enterprising young woman volunteers a DIY experiment as research for the story ‘How to get lips like Kylie Jenner without going under the knife’. (‘Kylie Jenner lip challenge’ is also, apparently, trending.) No changes to the last item—Donald Trump is, of course, always hot. Ideas are approved not because of their news value but on account of how they appeal to base emotions. And in this quarter of an hour, these ten youngsters have tapped into the whole range of American emotional triggers: what excites Americans, what terrifies them, what makes them sad, and what makes them curious.

This isn’t an editorial meeting somewhere in the US. Everyone here is less than twenty-three years old, and they’re perched in an all-glass office in a shopping mall in Indore, a medium-sized city in central India. They’re deciding, a few hours before America wakes up, what it will read when it does.

They are hardly ever wrong—or so say the numbers. Millions of people visit their website, WittyFeed, every day. Of them, 80 per cent are foreigners and half these people are from the US. WittyFeed is one of the world’s fastest-growing content farms; over a billion people follow it on Facebook alone. The only website of its kind visited by more people is BuzzFeed, the world leader in viral content. Currently valued at only 30 million dollars, WittyFeed is giving itself a couple of years to beat BuzzFeed. That’s not its ultimate goal, though. What the plucky youngsters who run it want to do is to build the world’s largest media company (‘bigger than BBC, CNN’). How do they hope to do it? By following their maxim: ‘It’s emotion that goes viral.’

Few people have heard of WittyFeed, even in India. The only reason I’m here is because I noticed its crazy numbers: 82 million monthly visits, 1.5 billion page views, 170 million users, 4.2 million likes on Facebook. WittyFeed is news by the same parameter that it uses to define news: the WTF factor. How can a bunch of kids in a small Indian town who have never seen the world dream of ruling it by simply getting the internet better than anyone else?

The Clay Toy-Cart: Mrchchakatikam by Shudraka – An Excerpt

Shudraka is regarded as one of the foremost Sanskrit dramatists. Although his work has been lauded for centuries, his real identity remains a mystery. The Clay Toy-Cart remains one of the foundational works of Sanskrit drama, having been performed numerous times around the world and even serving as the inspiration for Girish Karnad’s highly acclaimed film Utsav.

Here is an excerpt from this iconic play.

—————————————————-

Radanika: (Moving about in fear) Oh my God! A thief has made a hole in the wall of our house and is now getting away! Let me try and rouse Arya Maitreya. Arya Maitreya! Please wake up! A thief had breached the wall and has now got away!

Vidushaka: (Awakens) You daughter of a whore! What are you saying? The thief has been breached and the hole is getting away?

Radanika: No joking for heaven’s sake, you wretch! Can’t you see this? (Points to the hole)

Vidushaka: You daughter of a whore! What do you mean by saying it again as if a second door has been opened? (To Charudatta) Oh! My friend Charudatta! Get up! Get up! A thief has bored a hole in our wall and has disappeared!

Charudatta: (Having risen) All right, that is enough joking!

Vidushaka: I am not joking. You see for yourself.

Charudatta: Where is the hole?

Vidushaka: Over here.

Charudatta: (Looks at the hole and exclaims) But what a beautiful hole! The bricks have been removed from top down! This hole is small at the top and large in the middle. As though this is the heart of this great mansion. Split due to fear of contact with one unworthy. There is expertise even in this kind of work!

Vidushaka: My friend, undoubtedly this breach has been made by one of two kinds of people. Someone new to the city or one merely practising his art! For who in this Ujjayini does not know the state of our finances?

Charudatta: Perhaps a man from foreign parts did it, By way of practising his skill, no doubt. Or he knew not that we were men unburdened with wealth, Who could sleep on soundly with a light heart! His hopes were raised by the first sight of our huge mansion Only to be dashed to the ground. After the long and arduous task of boring the hole. But what will he tell his friends now, that he broke into the house of the scion of a great merchant but found nothing at all to carry away?

Vidushaka: Why do you waste your pity on that thieving rascal? He must have thought that this was such a great big house that surely he could make away with a treasure in gems and gold ornaments! . . . Where is that bundle of ornaments? (Recollecting suddenly) My friend, you always say Maitreya is a fool, Maitreya is ignorant; have I not done well in putting that parcel of ornaments into your hands? Otherwise that son of a whore would have made off with it!

Charudatta: Please, no more jokes.

Vidushaka: I may be a fool but I do know the time and the place for jokes.

Charudatta: When did all this happen?

Vidushaka: When I told you your hands were cold!

Charudatta: Ah! That could have been it! (Looks pleased) Thank God I can tell you something agreeable!

Vidushaka: What? Has it not been stolen?

Charudatta: No, it has been stolen.

Vidushaka: Then why are you pleased?

Charudatta: That he did not go away empty-handed.

Vidushaka: But it had been left in our safe custody!

Charudatta: Oh! It was in our safe custody! (He swoons)

Vidushaka: Please compose yourself. If what was left in our care has been stolen, why do you fall in a faint?

Charudatta: (Recovers) Who will believe the truth of the matter? The world will deride me, for poverty lacks dignity; It is suspect in the eyes of all. Alas! Fate had already eloped with my riches, Why does the cruel one seek to sully my good name as well now?

Vidushaka: I can deny everything, who gave and who received. And who indeed was the witness?

Charudatta: Would I now utter a falsehood? I would not flinch from begging to earn the means to redeem the loss Of what was left in my care; But a falsehood that would destroy my reputation I shall never utter.

Radanika: I had better go and report all this to my mistress Dhuta.

———————————-

An Indian Sense Of Salad by Tara Deshpande Tennebaum – An Excerpt

Tara Deshpande Tennebaum is a trained chef and author. She has studied at the French Culinary Institute in New York and at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris and London. In An Indian Sense of Salad: Eat Raw, Eat More, Tara Deshpande Tennebaum shows how to use fresh, local, easily available Indian vegetables, fruits, nuts and seeds, natural sweeteners and cold-pressed oils to prepare a range of raw and partially cooked salads from around the world.

Let’s read an excerpt from this book.

———————

Placing a salad in the Indian context is difficult because, historically, it occupies a very small part of our diet. Indian cuisine is one of the most multifarious I have ever encountered, and I say this after eighteen years of eating my way through Europe, Japan, China and the United States. The more I learn about Indian cuisine, the more I realize how little I know, despite having spent a majority of my life in the subcontinent.

That the sum of the parts doesn’t make the whole applies aptly to Indian cooking. We are masters of processing and enhancing food and magicians at creating flavours that didn’t exist before. That’s our métier. Take garam masala, for instance. If one were to change the ratio of even one spice, you’d have a new flavour.

Having said that, in India, we don’t favour the consumption of fresh produce or food in its raw form where every individual flavour is perceptible to the palate. Munching on roasted corn or swigging a glass of sugarcane juice outside the office block before heading home are probably the closest we come to consuming raw, unadorned foods. This is surprising because India has a limitless variety of fresh produce. We are the original harvesters of hundreds of varieties of vegetables, lentils, fruits and spices. Eggplant, bitter gourd, ginger, turmeric, pigeon pea, lime, bottle gourd, turnip, mango, jackfruit, cucumber and cumin are just some of the different kinds of produce that are native to India and South Asia. So if we simply go back to what we are good at—which is inventing flavours—and put that into creating unusual dressings and vinaigrettes to serve with raw ingredients that we usually ignore or cook into a pulp in Indian kitchens, we can create something extraordinary.

It’s at home that we should make salads a regular feature on the menu. I’m not promising you six-pack abs or the fountain of youth, nor is it my intention to push for a completely raw diet. But making raw fruits and veggies a component of your daily intake is an excellent idea. Organic food is still limited and expensive but where possibly do try and eat foods grown with less chemicals. Raw food has hardly any preservatives and additives, there are fewer toxins for the body to expel, and the benefits of good fibre, natural vitamins and minerals cannot be emphasized enough.

In the fifteenth century mud-covered root vegetables were considered less desirable and consumed by the poor while fruits and vegetables that grew above the ground were the purview of the rich. Produce such as potatoes and bananas were rumoured to cause sickness—poisoning even—in the early medieval period.

It was only in the sixteenth century that salads in their raw form reappeared in the homes of the wealthy. By the nineteenth century, salads began to develop into entire meals in America.

Many of India’s ancient culinary texts such as the Soopa Shastra (1508), Bhojana Kuthoohala (1670) and the Shiva Tatva Rathnakara (1700) contain elaborate descriptions of cooking vegetables and greens, including multiple ways to process eggplant and gooseberries and dozens of recipes for vadas and pongal. But when it comes to raw food, recipes are limited. In Manosolassa, the twelfth-century text, while the author Somesvara lists dozens of leafy vegetables and fruits that can be cured with lime juice, salt, ground spices and yogurt, there are barely a handful of recipes on raw green salads. It’s only when one gleans through the Ayurveda texts that one finds recipes using raw produce for medicinal concoctions. It makes you wonder if ‘raw’ in India came to be associated with sickness rather than luxury.

Salads are now being prepared by restaurants everywhere in urban India. There are more salads on a menu than soups. A salad, if well planned and constructed is possibly the best, healthiest course you can eat. So do try and make one at home every week. You can choose the recipe, buy the freshest ingredients and control the salt, sugar and oil. If you have to binge, find a salad you love with all your favourite flavours—sweet, spicy, sour. You’ll get lots of satisfaction and have a lot less guilt.

—————–

Seventy And to Hell with it! – An Excerpt

Shobhaa De, voted by Reader’s Digest as one of ‘India’s Most Trusted People’ and one of the ’50 Most Powerful Women in India’ by Daily News and Analysis, is one of India’s highest-selling authors and a popular social commentator. Her new book, Seventy and to Hell with it!, looks back on the terrain of her life. Especially at relationships-hers and those she has observed over the years-and at ever-present fears and grief.

Here’s an excerpt from this fun, entertaining and unputdownable book.

——————————————-

Nails. Would you believe it? Everything comes down to nails. Toenails. I am writing this soon after celebrating my sixty-seventh birthday with the family. As always, they had made it extraordinarily special for me. I felt a little guilty. Poor children and considerate husband—how much longer will they have to keep coming up with birthday surprises for me? Thoughtful, hand-picked gifts, sweet notes, an unexplored venue, candles and flowers. Year after year, my family has taken enormous trouble to make my birthday amazing— to make me feel amazing. This year, perhaps for the first time, I asked myself—do I deserve their love? The question depressed me. I came home in an uncharacteristically pensive mood. The mellow white wine we had consumed contributed to the introspection. Don’t get soppy and sentimental, I told myself. Don’t feel martyred. Feel happy, not guilty. Rejoice. Sixty-seven today, sixty-eight next year, sixty-nine the year after, seventy after that, life goes on.

The next morning, for the first time in my life, as I bent over to clip my toenails, I recoiled in shock. Those couldn’t possibly belong to me. These were the toenails of a really old person! I reached for my reading glasses and looked closely. My toenails had aged. Which meant the rest of me had aged too. But this drastically? Toenails never lie. Look at your own. Check what they are saying. Toenails tell you the sort of bald truths your face doesn’t. Perhaps it has something to do with being taken for granted. I had never thought about my toenails till that defining moment, the morning after my birthday. It was as if I was looking at them for the very first time in my life. And at that precise moment, I felt like I was staring at my mother’s feet. Those were her toenails when she was in her seventies.

It’s not about pedicures or caring enough for your feet. Nails cannot be fooled or pampered. Those damn toenails remind you to take a clear-eyed look at yourself—other body parts that are giving up, slowly but surely. Like the ropelike veins on the back of your hands, the loose skin under your chin and so many other telltale signs of physical deterioration. Since that day, I have started to examine my toenails every morning after my bath. I have scrupulously applied foot cream for years, but mechanically, without paying the slightest attention to the nails. Now that the toenails have become my main focus, I examine them somewhat obsessively. My toenails have started talking to me!

Old people’s nails thicken and are exceedingly hard to clip. They also get discoloured and ridged on the surface. By this point, chances of the toes getting misshapen are pretty high. Feet tend to flatten and broaden with advancing years. When that happens, toenails become brittle and crack vertically, which is very painful. The surrounding skin gets sore, leading to ingrown nails. Jagged edges appear, and get caught in bedclothes. You wake up in the middle of the night wincing in pain. It’s dark. You can’t find your spectacles. You grope on the bedside table, knock over a water jug. Switch on the light. Forget where you’ve stored the nail clipper. Wake up the husband and ask for help. The toenail-fixing operation gets under way. With eyes full of sleep, you nick yourself. There’s blood on the bed sheets. You need ice. You stagger to the kitchen. Wake up the dog. Wake up others. Slip on something squishy. Keel over. Fall. But not badly. Your old training as a sportsperson helps you break the fall. But there will be a bruise tomorrow morning. Ice cubes in hand, you make it back to the bedroom in one piece. Dawn is breaking. And your toenail still hasn’t been fixed. You finally feel old. Yes, old!

It took my toenails to remind me of my biological age. In my head and heart, I am stuck at thirty-four—possibly the best year of my life. That was a long time ago. But so what? What a year it was, tumultuous and life-altering. I decide there and then that no matter what my toenails are telling me, I will treat them as toenails, not as time bombs ticking away, warning me to be cautious, slow down, retire, find my inner calm, change. Sixty-seven is not all that terrible an age to be. If I continue to feel thirty-four, it doesn’t really matter.

That unexpected encounter with the toenails brought me face-to-face with the sixty-seven-year-old me. And forced me to shift my gaze upwards and look more closely into the mirror. All of a sudden, I took note of the deepening lines around the mouth, the additional crow’s feet at the corners of my eyes. The extra strands of grey framing my face, the slackening of the skin on the neck, the slight discoloration of the lips. My reflection was a revelation. How had I not noticed these changes earlier? Had I not looked hard enough? That’s not possible. I am as vain as the next person. I had looked but I hadn’t seen. Such a big difference between looking and seeing. Just as I was fretting over a deep furrow between the brows, I happened to catch a glimpse of my ears. Here’s a confession: I like my ears. And to my great satisfaction and utter relief, the ears looked just the same. The ears could have belonged to a thirty-four-year-old. And that was my big thrill. Why focus on the negatives (discoloured toenails) when there are positives (pretty ears) to cheer you up?

It’s important to be realistic and self-critical in life. But it’s equally important to remain upbeat and positive about the inevitable. Age is one of them. From now on, it’s going to be ears over toenails.

I am not going to put on a fake jaunty attitude and declare: Seventy is the new fifty! Because seventy is seventy. And no matter how ‘young’ you feel, you can neither look it nor hack it as anyone but a (hopefully) well-preserved septuagenarian. Life definitely does not begin at seventy—but neither does it have to end. I don’t believe in milestones. Hitting seventy is not an achievement. And it is certainly not a milestone. It is merely a biological fact of life. I have survived my seventh decade. That’s about all it says to me.

——————————–

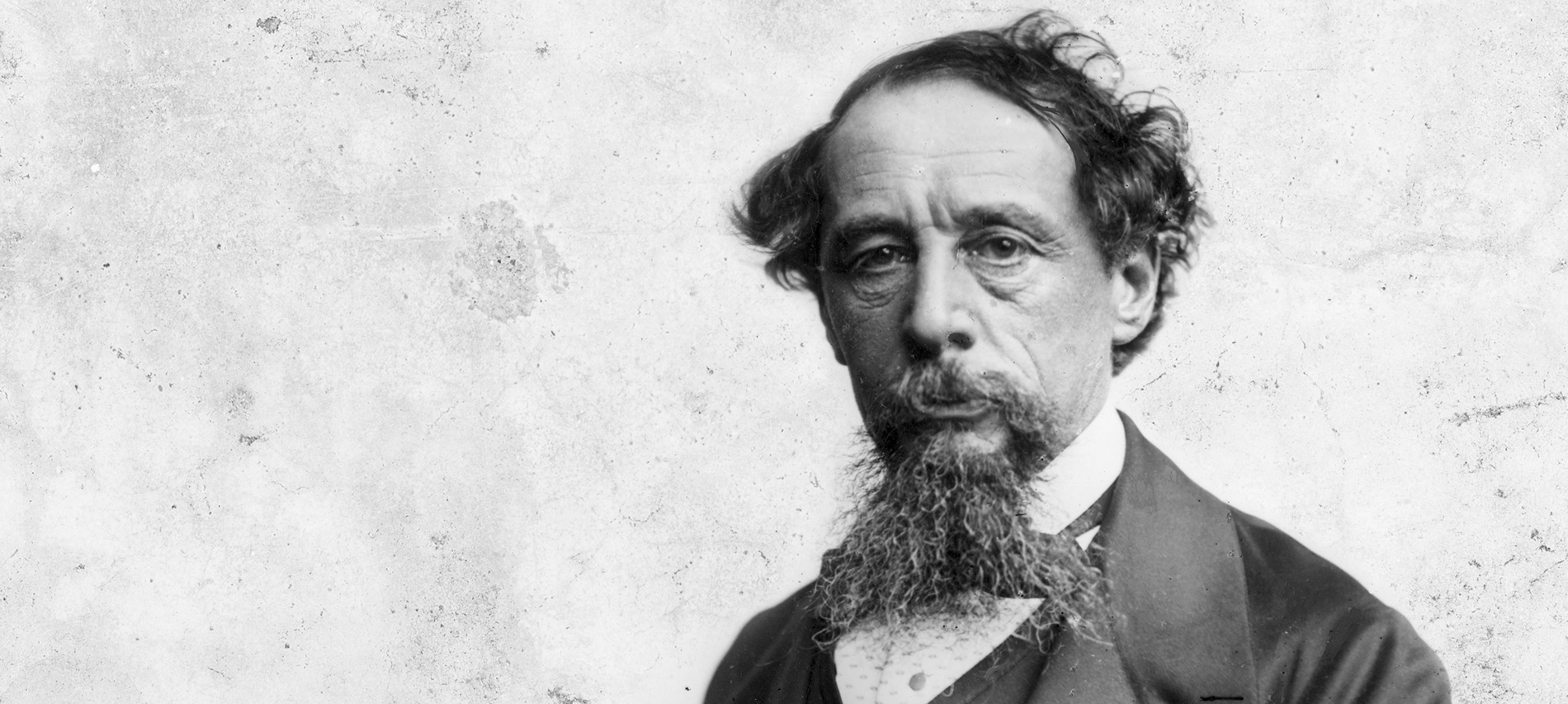

10 Books by Charles Dickens Every Millennial Should Read

Charles Dickens can easily be termed as a phenomenon. The English writer and social critic was a hardworking journalist and a great novelist. He created some of the most cherished characters in literature: the Artful Dodger, Mr Pickwick, Pip, David Copperfield, Little Nell, Lady Dedlock, and many more.

Here we take a look at his 10 books that should be on every Millennial’s list.

1. Great Expectations

In what may be Dickens’s best novel, humble, orphaned Pip is apprenticed to the dirty work of the forge but dares to dream of becoming a gentleman — and one day, under sudden and enigmatic circumstances, he finds himself in possession of “great expectations.”

In what may be Dickens’s best novel, humble, orphaned Pip is apprenticed to the dirty work of the forge but dares to dream of becoming a gentleman — and one day, under sudden and enigmatic circumstances, he finds himself in possession of “great expectations.”

2. A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities, portrays a world on fire, split between Paris and London during the brutal and bloody events of the French Revolution.

A Tale of Two Cities, portrays a world on fire, split between Paris and London during the brutal and bloody events of the French Revolution.

3. Bleak House

Regarded as Dickens’ masterpiece, the plot revolves around a long-running legal case entitled Jarndyce vs Jarndyce. Mixing romance, mystery, comedy, and satire, Bleak House limns the suffering caused by the intricate inefficiency of the law.

Regarded as Dickens’ masterpiece, the plot revolves around a long-running legal case entitled Jarndyce vs Jarndyce. Mixing romance, mystery, comedy, and satire, Bleak House limns the suffering caused by the intricate inefficiency of the law.

4. The Adventures of Oliver Twist

The Adventures of Oliver Twist is the story of a young orphan. It revolves around his childhood in a workhouse, his subsequent apprenticeship with an undertaker, his escape to London and finally his acquaintance with the Artful Dodger. It is both an angry indictment of poverty, and an adventure filled with an air of threat and pervasive evil.

The Adventures of Oliver Twist is the story of a young orphan. It revolves around his childhood in a workhouse, his subsequent apprenticeship with an undertaker, his escape to London and finally his acquaintance with the Artful Dodger. It is both an angry indictment of poverty, and an adventure filled with an air of threat and pervasive evil.

5. A Christmas Carol

Ebenezer Scrooge is a bitter, cold-hearted old miser lacking in Christmas spirit. He is visited by four ghosts, the ghost of his former business partner and the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come, who take Scrooge on respective journeys. One of the best-loved Yuletide tales by Dickens, a Christmas Carol is filled with compassion and humor.

Ebenezer Scrooge is a bitter, cold-hearted old miser lacking in Christmas spirit. He is visited by four ghosts, the ghost of his former business partner and the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come, who take Scrooge on respective journeys. One of the best-loved Yuletide tales by Dickens, a Christmas Carol is filled with compassion and humor.

6. David Copperfield

David Copperfield is the story of a young man’s adventures on his journey from an unhappy and impoverished childhood to the discovery of his vocation as a successful novelist. In David Copperfield – the novel he described as his ‘favourite child’ – Dickens drew revealingly on his own experiences to create one of the most exuberant and enduringly popular works, filled with tragedy and comedy in equal measure.

David Copperfield is the story of a young man’s adventures on his journey from an unhappy and impoverished childhood to the discovery of his vocation as a successful novelist. In David Copperfield – the novel he described as his ‘favourite child’ – Dickens drew revealingly on his own experiences to create one of the most exuberant and enduringly popular works, filled with tragedy and comedy in equal measure.

7. Little Dorrit

A masterly evocation of the state and psychology of imprisonment, Little Dorrit is one of the supreme works of Dickens’s maturity.

A masterly evocation of the state and psychology of imprisonment, Little Dorrit is one of the supreme works of Dickens’s maturity.

8. The Pickwick Papers

Few first novels have created as much popular excitement as The Pickwick Papers – a comic masterpiece that catapulted its twenty-four-year-old author to immediate fame. Readers were captivated by the adventures of the poet Snodgrass, the lover Tupman, the sportsman Winkle and, above all, by that quintessentially English Quixote, Mr Pickwick, and his cockney Sancho Panza, Sam Weller.

Few first novels have created as much popular excitement as The Pickwick Papers – a comic masterpiece that catapulted its twenty-four-year-old author to immediate fame. Readers were captivated by the adventures of the poet Snodgrass, the lover Tupman, the sportsman Winkle and, above all, by that quintessentially English Quixote, Mr Pickwick, and his cockney Sancho Panza, Sam Weller.

9. Our Mutual Friend

Charles Dickens’s last complete novel, Our Mutual Friend is a glorious satire spanning all levels of Victorian society. It centres on an inheritance – Old Harmon’s profitable dust heaps – and its legatees, young John Harmon, presumed drowned when a body is pulled out of the River Thames, and kindly dustman Mr Boffin, to whom the fortune defaults. The novel is richly symbolic in its vision of death and renewal in a city dominated by the fetid Thames, and the corrupting power of money.

Charles Dickens’s last complete novel, Our Mutual Friend is a glorious satire spanning all levels of Victorian society. It centres on an inheritance – Old Harmon’s profitable dust heaps – and its legatees, young John Harmon, presumed drowned when a body is pulled out of the River Thames, and kindly dustman Mr Boffin, to whom the fortune defaults. The novel is richly symbolic in its vision of death and renewal in a city dominated by the fetid Thames, and the corrupting power of money.

10. Dombey and Son

A compelling depiction of a man imprisoned by his own pride, Dombey and Son explores the devastating effects of emotional deprivation on a dysfunctional family and on society as a whole. In his introduction, Andrew Sanders discusses the character of Paul Dombey, business and family relationships in Dombey and Son and their similarities to Dickens’s own childhood.

A compelling depiction of a man imprisoned by his own pride, Dombey and Son explores the devastating effects of emotional deprivation on a dysfunctional family and on society as a whole. In his introduction, Andrew Sanders discusses the character of Paul Dombey, business and family relationships in Dombey and Son and their similarities to Dickens’s own childhood.

——————————————-

An excerpt from The End of India by Khushwant Singh

Khushwant Singh, India’s best-known writer and columnist has authored classics such as Train to Pakistan, I Shall Not Hear the Nightingale and Delhi. He was awarded the Padma Vibhushan in 2007. His book, The End of India forces us to confront the absolute corruption of religion that has made us among the most brutal people on earth.

Here’s an intriguing excerpt from one of its chapters:

——————

It was during British rule that Hindu nationalism took birth. The most powerful movement, the Arya Samaj, began under the leadership of Swami Dayanand Saraswati (1824-1883). His call ‘Back to the Vedas’ received wide response, particularly in northern India. Amongst the Arya Samaj converts was the Punjabi Lala Lajpat Rai (1865-1928) who was both an ardent Hindu and a leader of the Indian National Congress. So was Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920) of Maharashtra who revived the cult of Ganapati and coined the slogan ‘Swaraj is our birthright’. In due course of time, Hindu militant organizations took birth.

The most important of these was the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) founded in 1925 by Keshav Baliram Hedgewar (1889-1940) in Nagpur. He propagated the cause of a Hindu rashtra, a Hindu state. He was anti-Muslim and also anti-Gandhi, because the Mahatma strove for equal rights for all religions. Hedgewar was succeeded by M.S. Golwalkar, who was followed by Balasaheb Deoras. Together, these leaders, all charismatic and all unashamedly communal, strengthened the organization through fascist propaganda, strict discipline and targeted social work among the Hindus during calamities like earthquakes and famines and during Partition.

By 1990, the RSS had over one million members, who included, among others, Atal Behari Vajpayee, L.K. Advani, Murli Manohar Joshi, Uma Bharti—the last three charged with the destruction of the Babri Masjid on 6 December 1992—and Narendra Modi, the present poster boy of the Hindu right who presided over the pogrom in Gujarat. The RSS was, and is, anti-Muslim, anti-Christian and anti-left. It could be dismissed as a lunatic group as long as it remained on the fringes of mainstream politics. Not any more. Its political offshoot, the Bharatiya Jan Sangh, today’s Bharatiya Janata Party, had only two MPs in the Lok Sabha in 1984, but by 1991 it had 117. Today, with its allies, it rules the country.

There are now several other Hindu organizations as, if not more, militant than the RSS. There is the Shiv Sena led by the rabble- rouser Bal Thackerey, an admirer of Adolf Hitler. He started with a movement called ‘Maharashtra for Maharashtrians’ aimed at ousting South Indians from Bombay. His mission soon changed to ousting Muslims from India. In the last decade or so he has spread his tentacles across the country and boasts of his sainiks taking the leading part in destroying the mosque in Ayodhya. Perhaps as reward he has his quota of ministers in the central government. Besides the Shiv Sena, there are the more mischievous Bajrang Dal and the Vishva Hindu Parishad, currently leading the agitation to build a Ramjanmabhoomi temple on the exact site where the now-destroyed Babri Masjid stood—no matter what the government or the courts of law have to say. This is typical. Most members of the extended Sangh parivar regard themselves above the law of the land. They have arrogated to themselves the right to decide the fate of one billion Indians.

———–

10 Things about Issac John that every reader should know

Prior to pursuing writing, Issac led the marketing team at PUMA India for four years. In 2015, Pitch magazine nominated Issac as one of the Top 10 Young Marketers in India. Issac’s debut book, Buffering Love, is a collection of 15 short stories that has characters cling on to their mobile phones, sometimes to crush reality and sometimes to embellish it. Set in urban India and replete with surprising turns, these stories will delight and devastate its readers in equal measure.

You can follow Issac on his Instagram handle here.