Dan Brown is back with yet another novel in ‘ The Robert Langdon Series’ after Angels & Demons (2000), The Da Vinci Code (2003), The Lost Symbol (2009), and Inferno (2013).

‘Origin’, which is the 5th installment in Robert Langdon’s adventures, is based on Langdon’s travels in Spain. It moves forth with the same paradoxical power play between Religion and Science.

Let’s read more to find out what happens next in the first of our three excerpts from ‘Origin’

—-

Prologue

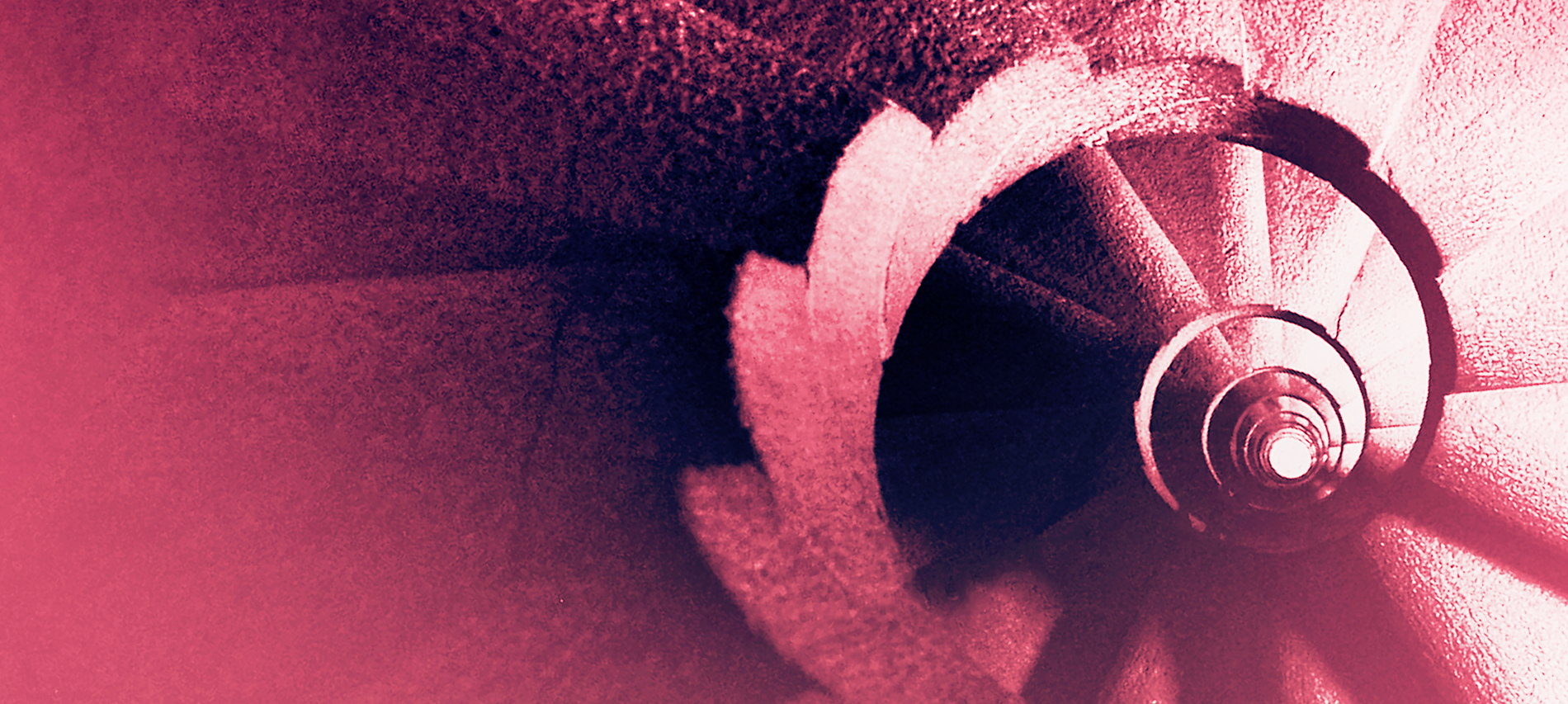

As the ancient cogwheel train clawed its way up the dizzying incline, Edmond Kirsch surveyed the jagged mountaintop above him. In the distance, built into the face of a sheer cliff, the massive stone monastery seemed to hang in space, as if magically fused to the vertical precipice.

This timeless sanctuary in Catalonia, Spain, had endured the relentless pull of gravity for more than four centuries, never slipping from its original purpose: to insulate its occupants from the modern world.

Ironically, they will now be the first to learn the truth, Kirsch thought, wondering how they would react. Historically, the most dangerous men on earth were men of God . . . especially when their gods became threatened. And I am about to hurl a flaming spear into a hornets’ nest.

When the train reached the mountaintop, Kirsch saw a solitary figure waiting for him on the platform. The wizened skeleton of a man was draped in the traditional Catholic purple cassock and white rochet, with a zucchetto on his head. Kirsch recognized his host’s rawboned features from photos and felt an unexpected surge of adrenaline.

Valdespino is greeting me personally.

Bishop Antonio Valdespino was a formidable figure in Spain—not only a trusted friend and counselor to the king himself, but one of the country’s most vocal and influential advocates for the preservation of conservative Catholic values and traditional political standards.

“Edmond Kirsch, I assume?” the bishop intoned as Kirsch exited the train.

“Guilty as charged,” Kirsch said, smiling as he reached out to shake his host’s bony hand. “Bishop Valdespino, I want to thank you for arranging this meeting.”

“I appreciate your requesting it.” The bishop’s voice was stronger than Kirsch expected—clear and penetrating, like a bell. “It is not often we are consulted by men of science, especially one of your prominence. This way, please.”

As Valdespino guided Kirsch across the platform, the cold mountain air whipped at the bishop’s cassock.

“I must confess,” Valdespino said, “you look different than I imagined. I was expecting a scientist, but you’re quite . . .” He eyed his guest’s sleek Kiton K50 suit and Barker ostrich shoes with a hint of disdain. “‘Hip,’ I believe, is the word?”

Kirsch smiled politely. The word “hip” went out of style decades ago.

“In reading your list of accomplishments,” the bishop said, “I am still not entirely sure what it is you do.” “I specialize in game theory and computer modeling.”

“So you make the computer games that the children play?”

Kirsch sensed the bishop was feigning ignorance in an attempt to be quaint. More accurately, Kirsch knew, Valdespino was a frighteningly well-informed student of technology and often warned others of its dangers. “No, sir, actually game theory is a field of mathematics that studies patterns in order to make predictions about the future.”

“Ah yes. I believe I read that you predicted a European monetary crisis some years ago? When nobody listened, you saved the day by inventing a computer program that pulled the EU back from the dead. What was your famous quote? ‘At thirty-three years old, I am the same age as Christ when He performed His resurrection.’”

Kirsch cringed. “A poor analogy, Your Grace. I was young.”

“Young?” The bishop chuckled. “And how old are you now . . . perhaps forty?”

“Just.”

The old man smiled as the strong wind continued to billow his robe. “Well, the meek were supposed to inherit the earth, but instead it has gone to the young—the technically inclined, those who stare into video screens rather than into their own souls. I must admit, I never imagined I would have reason to meet the young man leading the charge. They call you a prophet, you know.”

“Not a very good one in your case, Your Grace,” Kirsch replied. “When I asked if I might meet you and your colleagues privately, I calculated only a twenty percent chance you would accept.”

“And as I told my colleagues, the devout can always benefit from listening to nonbelievers. It is in hearing the voice of the devil that we can better appreciate the voice of God.” The old man smiled. “I am joking, of course. Please forgive my aging sense of humor. My filters fail me from time to time.”

With that, Bishop Valdespino motioned ahead. “The others are waiting. This way, please.”

Kirsch eyed their destination, a colossal citadel of gray stone perched on the edge of a sheer cliff that plunged thousands of feet down into a lush tapestry of wooded foothills. Unnerved by the height, Kirsch averted his eyes from the chasm and followed the bishop along the uneven cliffside path, turning his thoughts to the meeting ahead.

Kirsch had requested an audience with three prominent religious leaders who had just finished attending a conference here.

The Parliament of the World’s Religions.

Since 1893, hundreds of spiritual leaders from nearly thirty world religions had gathered in a different location every few years to spend a week engaged in interfaith dialogue. Participants included a wide array of influential Christian priests, Jewish rabbis, and Islamic mullahs from around the world, along with Hindu pujaris, Buddhist bhikkhus, Jains, Sikhs, and others.

The parliament’s self-proclaimed objective was “to cultivate harmony among the world’s religions, build bridges between diverse spiritualities, and celebrate the intersections of all faith.”

A noble quest, Kirsch thought, despite seeing it as an empty exercise— a meaningless search for random points of correspondence among a hodgepodge of ancient fictions, fables, and myths.

As Bishop Valdespino guided him along the pathway, Kirsch peered down the mountainside with a sardonic thought. Moses climbed a mountain to accept the Word of God . . . and I have climbed a mountain to do quite the opposite.

Kirsch’s motivation for climbing this mountain, he had told himself, was one of ethical obligation, but he knew there was a good dose of hubris fueling this visit—he was eager to feel the gratification of sitting face-to-face with these clerics and foretelling their imminent demise.

You’ve had your run at defining our truth.

“I looked at your curriculum vitae,” the bishop said abruptly, glancing at Kirsch. “I see you’re a product of Harvard University?”

“Undergraduate. Yes.”

“I see. Recently, I read that for the first time in Harvard’s history, the incoming student body consists of more atheists and agnostics than those who identify as followers of any religion. That is quite a telling statistic, Mr. Kirsch.”

What can I tell you, Kirsch wanted to reply, our students keep getting smarter.

The wind whipped harder as they arrived at the ancient stone edifice. Inside the dim light of the building’s entryway, the air was heavy with the thick fragrance of burning frankincense. The two men snaked through a maze of dark corridors, and Kirsch’s eyes fought to adjust as he followed his cloaked host. Finally, they arrived at an unusually small wooden door. The bishop knocked, ducked down, and entered, motioning for his guest to follow.

Uncertain, Kirsch stepped over the threshold.

He found himself in a rectangular chamber whose high walls burgeoned with ancient leather-bound tomes. Additional freestanding bookshelves jutted out of the walls like ribs, interspersed with cast-iron radiators that clanged and hissed, giving the room the eerie sense that it was alive. Kirsch raised his eyes to the ornately balustraded walkway that encircled the second story and knew without a doubt where he was.

The famed library of Montserrat, he realized, startled to have been admitted. This sacred room was rumored to contain uniquely rare texts accessible only to those monks who had devoted their lives to God and who were sequestered here on this mountain.

“You asked for discretion,” the bishop said. “This is our most private space. Few outsiders have ever entered.”

“A generous privilege. Thank you.”

Kirsch followed the bishop to a large wooden table where two elderly men sat waiting. The man on the left looked timeworn, with tired eyes and a matted white beard. He wore a crumpled black suit, white shirt, and fedora.

“This is Rabbi Yehuda Köves,” the bishop said. “He is a prominent Jewish philosopher who has written extensively on Kabbalistic cosmology.”

Kirsch reached across the table and politely shook hands with Rabbi Köves. “A pleasure to meet you, sir,” Kirsch said. “I’ve read your books on Kabbala. I can’t say I understood them, but I’ve read them.”

Köves gave an amiable nod, dabbing at his watery eyes with his handkerchief.

“And here,” the bishop continued, motioning to the other man, “you have the respected allamah, Syed al-Fadl.”

The revered Islamic scholar stood up and smiled broadly. He was short and squat with a jovial face that seemed a mismatch with his dark penetrating eyes. He was dressed in an unassuming white thawb. “And, Mr. Kirsch, I have read your predictions on the future of mankind. I can’t say I agree with them, but I have read them.”

Kirsch gave a gracious smile and shook the man’s hand.

“And our guest, Edmond Kirsch,” the bishop concluded, addressing his two colleagues, “as you know, is a highly regarded computer scientist, game theorist, inventor, and something of a prophet in the technological world. Considering his background, I was puzzled by his request to address the three of us. Therefore, I shall now leave it to Mr. Kirsch to explain why he has come.”

With that, Bishop Valdespino took a seat between his two colleagues, folded his hands, and gazed up expectantly at Kirsch. All three men faced him like a tribunal, creating an ambience more like that of an inquisition than a friendly meeting of scholars. The bishop, Kirsch now realized, had not even set out a chair for him.

Kirsch felt more bemused than intimidated as he studied the three aging men before him. So this is the Holy Trinity I requested. The Three Wise Men.

Pausing a moment to assert his power, Kirsch walked over to the window and gazed out at the breathtaking panorama below. A sunlit patchwork of ancient pastoral lands stretched across a deep valley, giving way to the rugged peaks of the Collserola mountain range. Miles beyond, somewhere out over the Balearic Sea, a menacing bank of storm clouds was now gathering on the horizon.

Fitting, Kirsch thought, sensing the turbulence he would soon cause in this room, and in the world beyond.

“Gentlemen,” he commenced, turning abruptly back toward them. “I believe Bishop Valdespino has already conveyed to you my request for secrecy. Before we continue, I just want to clarify that what I am about to share with you must be kept in the strictest confidence. Simply stated, I am asking for a vow of silence from all of you. Are we in agreement?”

All three men gave nods of tacit acquiescence, which Kirsch knew were probably redundant anyway. They will want to bury this information—not broadcast it.

“I am here today,” Kirsch began, “because I have made a scientific discovery I believe you will find startling. It is something I have pursued for many years, hoping to provide answers to two of the most fundamental questions of our human experience. Now that I have succeeded, I have come to you specifically because I believe this information will affect the world’s faithful in a profound way, quite possibly causing a shift that can only be described as, shall we say—disruptive. At the moment, I am the only person on earth who has the information I am about to reveal to you.”

Kirsch reached into his suit coat and pulled out an oversized smartphone—one that he had designed and built to serve his own unique needs. The phone had a vibrantly colored mosaic case, and he propped it up before the three men like a television. In a moment, he would use the device to dial into an ultra secure server, enter his forty-seven-character password, and live-stream a presentation for them.

“What you are about to see,” Kirsch said, “is a rough cut of an announcement I hope to share with the world—perhaps in a month or so. But before I do, I wanted to consult with a few of the world’s most influential religious thinkers, to gain insight into how this news will be received by those it affects most.”

Stay tuned for the second excerpt—

Origin by Dan Brown Releases on October 3’ 2017.

Preorder your copy today!

Category: Features

articles features main category

24 Books You Should Read This Month

Autumn is here and so is the season to go out and read. With cool fall breeze there to turn the pages of your book, what better way to enjoy the season but to immerse yourself in a great read.

Here are 24 books you should read this month.

The Shoonyam Quotient

Mickey Mehta, global leading wellness coach, and corporate life coach will show you how to be neither pessimistic nor optimistic, but optimized-primed to become the best version of yourself. The unique and motivational catchphrases and deep philosophical thoughts encapsulated in The Shoonyam Quotient will make you energized, content and peaceful.

The Golden House: A Novel

The story of the powerful Golden family is told from their neighbor and confidant, René’s point of view – an aspiring filmmaker who finds in the Goldens the perfect subject. The Golden House is about where we were before 26/11, where we are today and how we got here. The result is a modern epic of love and terrorism, loss, and reinvention- a powerful, timely story told with the daring and panache that makes Salman Rushdie a gleam of hope in our dark days.

Nostalgia

From one of Canada’s most celebrated writers and two-time Giller Prize winner, Moyez Vassanji, comes a taut, ingenuous and dynamic novel about a future where everything is possible. You will be granted an eternal life and freedom to choose your identity. Let’s explore this new territory of Vassanji’s brilliant writing.

Barefoot to Boots: The Many Lives of Indian Football

In Barefoot to Boots, renowned journalist Novy Kapadia reveals Indian football’s glorious legacy through a compelling detail of on-field action, stories of memorable matches, lively anecdotes, and exclusive conversations with legendary players and officials. The book will offer priceless insight into the future of the game as the Indian Super League dramatically changes the landscape of domestic football and India hosts the FIFA U-17 World Cup for the first time this year.

Words from the Hills

Words from the Hills offers a novel perspective to look at time and schedule forthcoming and bygone in a unique way. A biographical work developed around the life, works and philosophy of Ruskin Bond, in this planner we aim to catch those moments of pure joy. This planner (of 12/16 months), perhaps the first of its kind, will open a new window to our understanding of self-preservation and remembrance.

Songs of a Coward: Poems of Exile

Explore the liberating power of words in Songs of a Coward. Written by Perumal Murugan during a period of immense personal turmoil, these verses are an enduring testament to the resilience of an imagination under attack. By nature passionate, elegiac, tender, nightmarish and courageous, the poems in Songs of a Coward weave an exquisite tapestry of rich images and turbulent emotions in one’s darkest hour.

Prem Purana : Mythological Romances

Love is a universal feeling – it escapes no one -not even devas (gods) and asuras (demons), kings and nymphs. And when they face life’s unexpected tribulations, their love also undergoes trials. Tormented by passion, ravaged by betrayal, torn by the agony of separation, love in its many splendored forms is the origin of these incredibly endearing stories of Prem Purana.

You Never Know: Sometimes Love Can Drag You Through Hell

Dhruv knew Anuradha was his true love. But, despite this, he went ahead and fulfilled the desire of his body and mind. Akash Verma’s book You Never Know: Sometimes Love Can Drag You Through Hell will take you into a world of secret and dark revelations. What happens next? – is the question that will echo every time you flip a page.

Boo! 13 Stories That Will Send a Chill down your Spine

Boo is a collection of 13 well-crafted horror stories about a he-ghoul, a departed son’s soul, whispers and visitations from beyond, night howls, unearthly claws that erupt from bellies and the very first ghost in the world, among others. Penned by Shashi Deshpande, Kanishk Tharoor, K.R. Meera, Jerry Pinto, Usha K.R., Jahnavi Barua, Manabendra Bandyopadhyay, Ipsita Roy Chakraverti, Jaishree Misra, Kiran Manral, Madhavi S. Mahadevan, Durjoy Datta and Shinie Antony, the tales in Boo will surely spook you for a long time.

The Stardust Affair

Avinash Pawar, a young, undaunted reporter, works at the Mumbai Sun, alongside his mentor, Hamza Syed, a seasoned journalist who specializes in unearthing secrets about the city’s underworld. What starts out as a straightforward writing assignment quickly turns into a dangerous game where Avinash is playing for his life. Will he able be to escape from this dark world of drugs, crime, and deception?

Are You Connected ? 25 Keys to Live, Grow and Success with Self and Other

In this book, Acharya Venugopal, a monk from ISKCON, shares the different tools, skills, and experiences needed to help one connect to one’s own self, the people who matter and to God. Highlighting the need to go deeper into the meaning and purpose of life, Acharya offers skills to achieve peace of mind and to live in harmony with our true selves.

The Consolidators

The Consolidators talks about the second-generation entrepreneurs who tend to be the most interesting ones that have the controlling effect in business. In this highly original book, Prince displays the story of seven super successful second-generation entrepreneurs who showed imagination, gumption, and foresight in turning around the companies they inherited from their Fathers. In the most compelling way, this book will guide you to take your business to a sky-high reach.

Philosophia Perennis: Osho on Pythagoras I & II

Take a plunge into the world of Pythagoras. In a two-series collection, Osho expands on the perennial philosophy and the timeless laws of existence. In Philosophia Perennis 1,- Osho speaks on the ancient but little-known teachings of Pythagoras, his Golden Verses. In the second collection of talks on the timeless laws of existence, Osho talks about how the combination of seemingly polar opposites creates a unique meeting of religion and science. With the wisdom of Pythagoras, Osho blends in his insight to topics that include psychoanalysis, education, politics, revolution, sex and religion, making this book an exceptional read.

The Indian Spirit: The Untold Story of Alcohol in India

Wish to know where Drinking came from? Sit back and take delight in knowing the history of the drinking culture in India. The book is a treasure trove for those who have the palate to enjoy their drink and curiosity to know where it came from. Captured in the book are fascinating stories about alcohol, etiquettes of drinking and tasting notes on different spirits and brews!

Temporary People

Combining the irrepressible linguistic invention of Salman Rushdie and the satirical vision of George Saunders, Unnikrishnan presents twenty-eight linked stories that careen from construction workers who shapeshift into luggage and escape a labor camp, to a woman who stitches back together the bodies of those who’ve fallen from buildings in progress, to a man who grows ideal workers designed to live twelve years and then perish—until they don’t, and found a rebel community in the desert. With this polyphony, Unnikrishnan brilliantly maps a new, unruly global English.

India’s Most Fearless: True Stories of Modern Military Heroes

India’s Most Fearless covers fourteen true stories of extraordinary courage and fearlessness, providing a glimpse into the kind of heroism our soldiers display in unthinkably hostile conditions and under grave provocation. The Army major who led the legendary September 2016 surgical strikes on terror launch pads across the LoC; a soldier who killed 11 terrorists in 10 days are some of the true stories of heroism in the book.

On The Dessert Trail

Monish Gujral is back with his scrumptious detail of signature recipes from his travels across the world. A cookbook author, chef, restaurateur and popular blogger, Gujral presents these recipes with his own blend of ingredients. He simplifies the processes so that you can make them at home, at your pace, and in your comfort zone. This book is a home cook’s delight and a must-have for those who crave to satisfy their sweet tooth.

SHOOT. DIVE. FLY

Read twenty-one nail-biting stories of daring in Shoot.Dive.Fly. Lend your ear to brave men and women, on their stories about what the forces have taught them-and to decide if the olive green uniform is what you want to wear too. SHOOT., DIVE., FLY aims to introduce teenagers to the armed forces and ignite the fire in them, come face to face with perils-the rigours and the challenges-and perks-the thrill and the adventure of a career in uniform.

Republic of Rhetoric : For Speech & Constitution of India

India got her independence long time back. The book explores socio-political as well as legal history of India, from the British period to the present. It sheds light on the idea of ‘free speech’ or what is popularly known as the freedom expression in the country. Analysing the present law relating to obscenity and free speech, this book evaluates whether the enactment of the Constitution made a significant difference in the Indian social fabric relating to the right to free speech in India.

The Boys Who Fought

Pattanaik’s new book is back with an illustrated retelling of the Mahabharata to illuminate and captivate a new generation of readers. ‘When you can fight for the meek without hating the mighty, you follow dharma.’ In the forest, the mighty eat the meek. In human society, the mighty should take care of the meek. This is dharma. A hundred princes should look after their five orphaned cousins. Instead, they burnt their house, abused their wife and stole their kingdom. The five fought back, not for revenge but, for dharma. What happened later? What came of the five’s battle against the hundreds?

The Last Vicereine

India was on the brink of civil war when Lord and Lady Mountbatten arrived in New Delhi. The reluctant Vicereine was a rebel, a rule-breaker. She was a perturbed soul, a great beauty, a firecracker but there was more to her than we could envision. The glamour was a façade; behind it was a highly intelligent woman of influence and power. The Last Vicereine is a heartbreaking story which witnesses the tumultuous phase of the birth of two nations, and of love, grief, tragedy, inhumanity and the triumph of hope.

So, which book are you picking this month?

6 books You Should Read This Navratri

Navratri is a celebration of womanhood and the different forms of a woman. The various goddesses in Hinduism embody different ideals.

Here’s a list of 6 books to celebrate the power of women, this Navratri

Like Durga with her ten arms defeated Mahishasura on the battlefield, Sudha Menon’s book Devi, Diva or She-Devil explores the plethora of challenges women face in the professional world and deal with them.

Step Up : How Women Can Perform Better For Success

In an effort to help women achieve the ultimate goal in their personal and professional space, author Anju Jain in Step Up elucidates practical techniques in a simple matrix for women to become successful. The book features interviews with key figures such as Kiran Mazumdar Shaw (Biocon), Sonia Singh (NDTV), Devyani Rana (Caterpillar), Geetu Verma (Unilever) which shows how the modern day woman embodies Goddess Shakti and triumphs over personal and professional arenas.

Millionaire Housewives

In this book, the authors explore the lives of 12 enterprising homemakers who in spite of having no past experience in business, managed to build successful empires through their ambitious zeal for work, defying all stereotypes. Extending their good luck charm in business, they are the Lakshmis of the house who embody prosperity and wealth.

Kali

Seema Mohanty traces the evolution of the Goddess Kali in her book The Book of Kali. The goddess confronts the world in her unconventional persona – challenging the orthodox ideas of divinity. This book highlights the various forms and rituals associated in which the goddess is worshipped.

Jaya

In a modern re-telling of the Mahabharata, Devdutt Patnaik’s book Jaya not only features 250 line illustrations, it also includes women’s stories, other than Draupadi’s such as Satyawati, Kunti, Gandhari). The ending is not what one would expect, and almost is the sole reason why the book was originally called Jaya by Vyasa.

Sita

History has romanticised Rama at the cost of marginalizing the role that Sita played in ‘The Ramayana’. Devdutt Pattanaik’s book Sita re-imagines the world of Sita. It emphasizes on the fact that though portrayed as a submissive character, Sita was a woman of mighty demeanor and strength.

Which book are you reading this Navratri?

The Elements of a Successful Business Model

EVERY SUCCESSFUL COMPANY ALREADY operates according to an effective business model. By systematically identifying all of its constituent parts, executives can understand how the model fulfills a potent value proposition in a profitable way using certain key resources and key processes. With that understanding, they can then judge how well the same model could be used to fulfill a radically different CVP—and what they’d need to do to construct a new one, if need be, to capitalize on that opportunity.

When Ratan Tata of Tata Group looked out over this scene, he saw a critical job to be done: providing a safer alternative for scooter families. He understood that the cheapest car available in India cost easily five times what a scooter did and that many of these families could not afford one. Offering an affordable, safer, all-weather alternative for scooter families was a powerful value proposition, one with the potential to reach tens of millions of people who were not yet part of the car-buying market. Ratan Tata also recognized that Tata Motors’ business model could not be used to develop such a product at the needed price point.

At the other end of the market spectrum, Hilti, a Liechtensteinbased manufacturer of high-end power tools for the construction industry, reconsidered the real job to be done for many of its current customers. A contractor makes money by finishing projects; if the required tools aren’t available and functioning properly, the job doesn’t get done. Contractors don’t make money by owning tools; they make it by using them as efficiently as possible. Hilti could help contractors get the job done by selling tool use instead of the tools themselves—managing its customers’ tool inventory by providing the best tool at the right time and quickly furnishing tool repairs, replacements, and upgrades, all for a monthly fee. To deliver on that value proposition, the company needed to create a fleetmanagement program for tools and in the process, shift its focus from manufacturing and distribution to service. That meant Hilti had to construct a new profit formula and develop new resources and new processes.

The most important attribute of a customer value proposition is its precision: how perfectly it nails the customer job to be done—and nothing else. But such precision is often the most difficult thing to achieve. Companies trying to create the new often neglect to focus on one job; they dilute their efforts by attempting to do lots of things. In doing lots of things, they do nothing really well.

One way to generate a precise customer value proposition is to think about the four most common barriers keeping people from getting particular jobs done: insufficient wealth, access, skill, or time. Software maker Intuit devised QuickBooks to fulfill smallbusiness owners’ need to avoid running out of cash. By fulfilling that job with greatly simplified accounting software, Intuit broke the skills barrier that kept untrained small-business owners from using more-complicated accounting packages. MinuteClinic, the drugstore-based basic health care provider, broke the time barrier that kept people from visiting a doctor’s office with minor health issues by making nurse practitioners available without appointments.

Designing a profit formula

Ratan Tata knew the only way to get families off their scooters and into cars would be to break the wealth barrier by drastically decreasing the price of the car. “What if I can change the game and make a car for one lakh?” Tata wondered, envisioning a price point of around US$2,500, less than half the price of the cheapest car available. This, of course, had dramatic ramifications for the profit formula: It required both a significant drop in gross margins and a radical reduction in many elements of the cost structure. He knew; however, he could still make money if he could increase sales volume dramatically, and he knew that his target base of consumers was potentially huge.

For Hilti, moving to a contract management program required shifting assets from customers’ balance sheets to its own and generating revenue through a lease/subscription model. For a monthly fee, customers could have a full complement of tools at their fingertips, with repair and maintenance included. This would require a fundamental shift in all major components of the profit formula: the revenue stream (pricing, the staging of payments, and how to think about volume), the cost structure (including added sales development and contract management costs), and the supporting margins and transaction velocity.

Identifying key resources and processes

Having articulated the value proposition for both the customer and the business, companies must then consider the key resources and processes needed to deliver that value. For a professional services firm, for example, the key resources are generally its people, and the key processes are naturally people related (training and development, for instance). For a packaged goods company, strong brands and well-selected channel retailers might be the key resources, and associated brand-building and channel-management processes among the critical processes.

Oftentimes, it’s not the individual resources and processes that make the difference but their relationship to one another. Companies will almost always need to integrate their key resources and processes in a unique way to get a job done perfectly for a set of customers. When they do, they almost always create enduring competitive advantage. Focusing first on the value proposition and the profit formula makes clear how those resources and processes need to interrelate. For example, most general hospitals offer a value proposition that might be described as, “We’ll do anything for anybody.” Being all things to all people requires these hospitals to have a vast collection of resources (specialists, equipment, and so on) that can’t be knit together in any proprietary way. The result is not just a lack of differentiation but dissatisfaction.

By contrast, a hospital that focuses on a specific value proposition can integrate its resources and processes in a unique way that delights customers. National Jewish Health in Denver, for example, is organized around a focused value proposition we’d characterize as, “If you have a disease of the pulmonary system, bring it here. We’ll define its root cause and prescribe an effective therapy.” Narrowing its focus has allowed National Jewish to develop processes that integrate the ways in which its specialists and specialized equipment work together.

For Tata Motors to fulfill the requirements of its customer value proposition and profit formula for the Nano, it had to reconceive how a car is designed, manufactured, and distributed. Tata built a small team of fairly young engineers who would not, like the company’s more-experienced designers, be influenced and constrained in their thinking by the automaker’s existing profit formulas. This team dramatically minimized the number of parts in the vehicle, resulting in a significant cost saving. Tata also reconceived its supplier strategy, choosing to outsource a remarkable 85% of the Nano’s components and use nearly 60% fewer vendors than normal to reduce transaction costs and achieve better economies of scale.

At the other end of the manufacturing line, Tata is envisioning an entirely new way of assembling and distributing its cars. The ultimate plan is to ship the modular components of the vehicles to a combined network of company-owned and independent entrepreneur-owned assembly plants, which will build them to order. The Nano will be designed, built, distributed, and serviced in a radically new way—one that could not be accomplished without a new business model. And while the jury is still out, Ratan Tata may solve a traffic safety problem in the process.

This is an excerpt from HBR’s 10 Must Reads (On Strategy). Get your copy here.

Credit: Abhishek Singh

The Consolidators: An Excerpt

‘The Consolidators’ by Prince Mathews Thomas tells the story of seven second-generation entrepreneurs who display an arresting imagination and interest in evolving the business they inherited from their fathers.

Here’s an excerpt from the book which highlights Abhishek Khaitan’s tussle between one’s own desired profession vs the one chosen by the parents.

In many ways, the situation that Abhishek found himself in upon returning home from his studies in Bengaluru was similar to what his father Lalit had faced many years ago. The senior Khaitan too had harboured dreams of higher studies. ‘In those days there were two choices for us—law or chartered accountancy. I wanted to do law,’ he says.

The larger Khaitan families had quite a few eminent lawyers, including Devi Prasad Khaitan, founder of Khaitan & Co, the country’s third largest law firm, which completed a century of practice in 2010. Devi Prasad was part of the drafting committee that prepared the Constitution of India.

But being the oldest among his brothers and cousins, Lalit was asked by his father and uncle to study commerce at St. Xavier’s College in Kolkata, and at the same time join the family business. So after completing his classes for the day, Lalit would head to the bakery or the restaurant near Park Street that the family owned.

And then he was married at nineteen.

This—joining the family business and marrying early—was the norm in Marwari families. It was a tradition that had stood the test of time.

Many among the following generations of the family became leading lawyers, cementing the legacy of the Khaitan family in the country’s legal fraternity. A few of the Khaitans chose to do business and ventured into several industries—education, tea, batteries, cinema, restaurants, fertilizers and chemicals. Lalit’s father, G.N. Khaitan, also chose to do business.

Along with his brother, G.N. dabbled in several businesses— furniture, soap making, bakery, restaurants and a general provisions store. ‘We were a joint family. We were nine children living under the same roof [we were four brothers and a sister, and uncle had a daughter and three sons.Everything was done jointly, everything was shared. And we would all even sleep together in the same room. We didn’t have much money and were just a little above middle-class, or an upper middle-class family,’ says Lalit.

His father, called Gajju or Gajanand by his friends, was a well-known personality in Kolkata’s vibrant social circle. He had headed several institutions, including business bodies such as the Bharat Chamber of Commerce, Export Council of Engineering, and other organizations like the Indian Red Cross Society, and some popular clubs like Rajasthan Club and Bengal Rowing Club.

‘He used to be known for his bow tie. He never wore a regular tie in his life. He was very well connected, even in Bollywood. Once, he arranged a cricket match in Kolkata that had most of the biggest Bollywood names, including Raj Kapoor, attending. Shailesh Khaitan, my youngest brother, remembers the actor telling my father, “Khaitan sahib, you have got the whole of Bollywood here. If the plane crashes, Bollywood is dead”.’

Actor Pran, the legendary villain of Indian cinema, and often more popular than the heroes, was a close friend. ‘He would often drop by at our house in Kolkata. Once he was visiting after Zanjeer (a film that famously starred Amitabh Bachchan and Jaya Bhaduri) had released. I remarked that Amitabh had done a great job. Pran retorted, “What did he do? I did everything!”’

Grab your copy of The Consolidators now!

8 Steps to Improve Your Quality Of Life And Achieve Your Goal

We all dream about a glorious future and set goals to turn it into a reality. What if someone told you that you only need 5 years to achieve your goals.

Arfeen Khan in Where will you be in 5 years gives you crucial tips that are practical, effective and can be implemented from day one. He also helps you chart out your growth and solve your personal problems.

Here are 8 steps that he insists will help you improve your quality of life

Take Control of Your Health

Grow Your Wealth in a Steady Manner

How Passionate Are You about Your Work?

When Someone Knows You Better than You Know Yourself

Stay Curious and You Will Enjoy Life

Things Belong to You, You Don’t Belong to Them

How to Be Creative? Play Games

Stay Tuned to Your Social Support System

Tell us what do you do to improve the quality of life.

‘A Bewildering Mosaic of Communities’: ‘Left, Right and Centre: The Idea of India’ — An Excerpt

Diverse discourses born from diverse cultures, histories and geographies of India come together in senior journalist, Nidhi Razdan’s book ‘Left, Right and Centre: The Idea of India’.

Author and Indian academic, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, discusses the inherent dichotomy in the celebration of this ‘diversity’ in India in his essay ‘India: From Identity to Freedom’.

Here’s an excerpt from Mehta’s essay.

India is a diverse country, a bewildering mosaic of communities of all kinds; its peculiar genius is to fashion a form of coexistence where this diversity can flourish and find its place. It has created cultures of political negotiation that have shown a remarkable ability to incorporate diversity.

This description of India is often exhilarating; and it is our dominant mode of self-presentation. But it’s very attractiveness hides its deep problems. The problem lies with the normative valorization of diversity itself. Diversity is something to be celebrated and cherished for often it is an indication of other values like freedom and creativity. But diversity has become a source of several intellectual confusions. Very schematically these are: Diversity is not itself a freestanding moral value. It makes very little sense to discuss diversity as carrying independent moral weight, even though under some circumstances, loss of diversity can be an indication of other underlying injustices. The invocation of diversity immediately invites the question: Diversity of what? This question cannot be answered without invoking some normative criteria about the permissible range of social practices. The limits to diversity cannot themselves be settled by an invocation of diversity.

The appeal to diversity is usually an aestheticized appeal. It is as if one were surveying the world from nowhere and contemplating this extraordinary mosaic of human cultural forms and practices. Such a contemplation of the world can give enormous enrichment and satisfaction and we feel that something would be lost; perhaps something of humanity would be diminished if this diversity were lost. But the trouble is that this view from nowhere, or if you prefer an alternative formulation, the ‘God’s Eye’ view of the world is a standpoint of theoretical, not practical, reason.

Most of us can conceptually grasp the fact of diversity; we may even try to recognize each other in an intense and important way, but it is very difficult to live that diversity with any degree of seriousness. From this theoretical point of view, cultures and practices form this extraordinary mosaic; from the practical point of view of those living within any of these cultures, these cultures and practices are horizons within which they operate. Even when not oppressive, these horizons might appear to them as constraints. It would be morally obtuse to say to these individuals that they should go on living their cultures, just because they’re not doing so might diminish the forms of diversity in the world. The imperatives of diversity cannot, at least prima facie, trump the free choices of individuals.

There is often a real tension between the demands of integration into wider society—the imperatives of forming thicker relationships with those outside the ambit of your own society on the one hand, and the measures necessary to preserve a vibrant cultural diversity on the other. What the exact trade-off is depends from case to case. But simply invoking diversity by itself will not help morally illuminate the nature of the decision to be made when faced with such a trade-off.

From this perspective, talk of identity and diversity is profoundly misleading because it places value on the diversity of cultures, not the freedoms of individuals within them. If the range of freedom expands, all kinds of diversity will flourish anyway. But this will not necessarily be the diversity of well defined cultures. It will be something that both draws upon culture and subverts it at the same time.

Diversity Talk is compatible with only one specific conception of toleration: segmented and hierarchical toleration. To be fair, India has been remarkably successful at providing a home for all kinds of groups and cultures. But each group could find a place because each group had its fixed place. To put it very schematically, it was a form of toleration compatible with walls between communities. Indeed, one of the major challenges for Indian society is that we have internalized forms of toleration that are suited to segmented societies. It is compatible with the idea that boundaries should not be crossed, populations should not mix, and that to view the world as a competition between groups is fine.

There is no country in the world that talks so much of diversity. Yet no other country produces such a suffocating discourse of identity; where who you are seems to matter at every turn: what job you can get, what government scheme you are eligible for, how much institutional autonomy you can get, what house you can rent. Conceptually, there is no incompatibility between celebrating diversity of the nation and refusing to rent housing to a Muslim just because they are Muslim. Such a conception of toleration does not work where the need is for boundaries to be crossed: people will inhabit the same spaces, compete for the same jobs, intermarry and so forth. Our moral discourse is so centred on diversity and pluralism that it forgets the more basic ideas of freedom and dignity.

Explore diverse opinions from some of the best minds in India with ‘Left, Right and Centre: The Idea of India’.

8 Things that Scaachi Koul Said that Will Always Matter (Even When We are All Dead)

As children growing up, we tend to question everything and everyone. More often than not, we rebel against age-old customs imposed on us at every step, only to be told by our elders that we are too young to understand the ways of the world. Amidst this hormonal and social chaos that we are suddenly pushed into, it can be difficult to know that you’re not the only one who feels this way. Sometimes you just need someone to tell you that at the end, everything will turn out to be just fine.

Here are 8 times Indian-origin Canadian writer Scaachi Koul said things that would have made growing up so much easier.

When she told us that it’s okay to be any size, but not okay to be shamed for it.

When she showed us how a piece of clothing might define our waistlines, but not how we are as human beings.

When she taught us how it’s important to rationally question everything, including our parents.

When she held a mirror to our society’s face and magnified the ugly truth.

When she reminded us of our first childhood heroes.

When she showed us why it’s alright to do everything ‘forbidden’ and not feel guilty.

When her humour was self-deprecating, yet, damn honest.

And finally, when she told us exactly what we all need to know…

So, what is your advice to your teenage self?

Managing ADT (Attention Deficiency Trait)

D Overloaded Circuits by Edward M. Hallowell DAVID DRUMS HIS FINGERS on his desk as he scans the e-mail on his computer screen. At the same time, he’s talking on the phone to an executive halfway around the world. His knee bounces up and down like a jackhammer. He intermittently bites his lip and reaches for his constant companion, the coffee cup. He’s so deeply involved in multitasking that he has forgotten the appointment his Outlook calendar reminded him of 15 minutes ago.

Jane, a senior vice president, and Mike, her CEO, have adjoining offices so they can communicate quickly, yet communication never seems to happen. “Whenever I go into Mike’s office, his phone lights up, my cell phone goes off, someone knocks on the door, he suddenly turns to his screen and writes an e-mail, or he tells me about a new issue he wants me to address,” Jane complains. “We’re working flat out just to stay afloat, and we’re not getting anything important accomplished. It’s driving me crazy.”

David, Jane, and Mike aren’t crazy, but they’re certainly crazed. Their experience is becoming the norm for overworked managers who suffer—like many of your colleagues, and possibly like you— from a very real but unrecognized neurological phenomenon that I call attention deficit trait, or ADT.

Caused by brain overload, ADT is now epidemic in organizations. The core symptoms are distractibility, inner frenzy, and impatience. People with ADT have difficulty staying organized, setting priorities, and managing time. These symptoms can undermine the work of an otherwise gifted executive. If David, Jane, Mike, and the millions like them understood themselves in neurological terms, they could actively manage their lives instead of reacting to problems as they happen.

As a psychiatrist who has diagnosed and treated thousands of people over the past 25 years for a medical condition called attention deficit disorder, or ADD (now known clinically as attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder), I have observed firsthand how a rapidly growing segment of the adult population is developing this new, related condition. The number of people with ADT coming into my clinical practice has mushroomed by a factor of ten in the past decade. Unfortunately, most of the remedies for chronic overload proposed by time-management consultants and executive coaches do not address the underlying causes of ADT.

Unlike ADD, a neurological disorder that has a genetic component and can be aggravated by environmental and physical factors, ADT springs entirely from the environment. Like the traffic jam, ADT is an artifact of modern life. It is brought on by the demands on our time and attention that have exploded over the past two decades. As our minds fill with noise—feckless synaptic events signifying nothing—the brain gradually loses its capacity to attend fully and thoroughly to anything.

The symptoms of ADT come upon a person gradually. The sufferer doesn’t experience a single crisis but rather a series of minor emergencies while he or she tries harder and harder to keep up. Shouldering a responsibility to “suck it up” and not complain as the workload increases, executives with ADT do whatever they can to handle a load they simply cannot manage as well as they’d like. The ADT sufferer therefore feels a constant low level of panic and guilt. Facing a tidal wave of tasks, the executive becomes increasingly hurried, curt, peremptory, and unfocused, while pretending that everything is fine.

To control ADT, we first have to recognize it. And control it we must, if we as individuals and organizational leaders are to be effective. In the following pages, I’ll offer an analysis of the origins of ADT and provide some suggestions that may help you manage it.

This is an excerpt from HBR’s 10 Must Reads (On Managing Yourself). Get your copy here.

Credit: Abhishek Singh

Everything You Need to Know About Level 5 Leadership

IN 1971, A SEEMINGLY ordinary man named Darwin E. Smith was named chief executive of Kimberly-Clark, a stodgy old paper company whose stock had fallen 36% behind the general market during the previous 20 years. Smith, the company’s mild-mannered in-house lawyer, wasn’t so sure the board had made the right choice—a feeling that was reinforced when a Kimberly-Clark director pulled him aside and reminded him that he lacked some of the qualifications for the position. But CEO he was, and CEO he remained for 20 years.

What a 20 years it was. In that period, Smith created a stunning transformation at Kimberly-Clark, turning it into the leading consumer paper products company in the world. Under his stewardship, the company beat its rivals Scott Paper and Procter & Gamble. And in doing so, Kimberly-Clark generated cumulative stock returns that were 4.1 times greater than those of the general market, outperforming venerable companies such as Hewlett-Packard, 3M, CocaCola, and General Electric.

Smith’s turnaround of Kimberly-Clark is one the best examples in the twentieth century of a leader taking a company from merely good to truly great. And yet few people—even ardent students of business history—have heard of Darwin Smith. He probably would have liked it that way. Smith is a classic example of a Level 5 leader—an individual who blends extreme personal humility with intense professional will. According to our five-year research study, executives who possess this paradoxical combination of traits are catalysts for the statistically rare event of transforming a good company into a great one. (The research is described in the sidebar “One Question, Five Years, 11 Companies.”)

“Level 5” refers to the highest level in a hierarchy of executive capabilities that we identified during our research. Leaders at the other four levels in the hierarchy can produce high degrees of success but not enough to elevate companies from mediocrity to sustained excellence. (For more details about this concept, see the exhibit “The Level 5 Hierarchy.”) And while Level 5 leadership is not the only requirement for transforming a good company into a great one— other factors include getting the right people on the bus (and the wrong people off the bus) and creating a culture of discipline—our research shows it to be essential. Good-to-great transformations don’t happen without Level 5 leaders at the helm. They just don’t.

Not What You Would Expect

Our discovery of Level 5 leadership is counterintuitive. Indeed, it is countercultural. People generally assume that transforming companies from good to great requires larger-than-life leaders—big personalities like Lee Iacocca, Al Dunlap, Jack Welch, and Stanley Gault, who make headlines and become celebrities.

Compared with those CEOs, Darwin Smith seems to have come from Mars. Shy, unpretentious, even awkward, Smith shunned attention. When a journalist asked him to describe his management style, Smith just stared back at the scribe from the other side of his thick black-rimmed glasses. He was dressed unfashionably, like a farm boy wearing his first J.C. Penney suit. Finally, after a long and uncomfortable silence, he said, “Eccentric.” Needless to say, the Wall Street Journal did not publish a splashy feature on Darwin Smith.

But if you were to consider Smith soft or meek, you would be terribly mistaken. His lack of pretense was coupled with a fierce, even stoic, resolve toward life. Smith grew up on an Indiana farm and put himself through night school at Indiana University by working the day shift at International Harvester. One day, he lost a finger on the job. The story goes that he went to class that evening and returned to work the very next day. Eventually, this poor but determined Indiana farm boy earned admission to Harvard Law School.

He showed the same iron will when he was at the helm of Kimberly-Clark. Indeed, two months after Smith became CEO, doctors diagnosed him with nose and throat cancer and told him he had less than a year to live. He duly informed the board of his illness but said he had no plans to die anytime soon. Smith held to his demanding work schedule while commuting weekly from Wisconsin to Houston for radiation therapy. He lived 25 more years, 20 of them as CEO. Smith’s ferocious resolve was crucial to the rebuilding of Kimberly-Clark, especially when he made the most dramatic decision in the company’s history: selling the mills.

This is an excerpt from HBR’s 10 Must Reads (On Leadership). Get your copy here.

Credit: Abhishek Singh