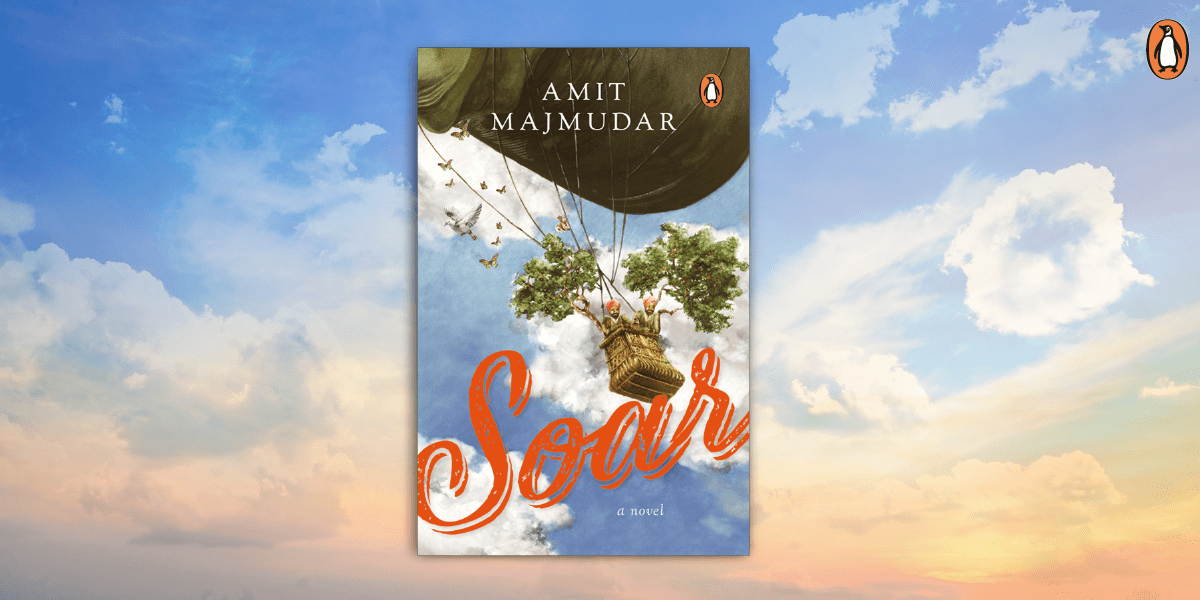

Bholanath and Khudabaksh are two soldiers in the British Indian Army, sent off to Europe to fight in World War I. One happens to be Hindu and the other happens to be Muslim, but that doesn’t keep them from being the best of friends.

When a mission in a surveillance balloon goes awry, these two gentle soldiers-along with an exceptionally ill-tempered squirrel-are set adrift high above the Western Front.

Intrigued? Read an excerpt from Soar:

—

The two soldiers kept searching the forest for food. The only thing they found, and this only when Bholanath stubbed his toe and punctured a hollow, half-rotted log, was a clutch of gray mushrooms. They began hunting in such dark hideaways for more mushrooms, and eventually had collected whole pocketsfull of them, dirt-speckled and with droopy caps of various dun colors. Only one variety was orange. Bholanath blew the dirt off it.

“These may be good for breakfast, seeing as we have no fruit.”

They took their harvest back to the stream, where they dunked each mushroom and let the current rinse it, rubbing the more stubborn dirt stains with their thumbs. The orange caps proved even brighter after the washing. He handed Khudabaksh a few and kept a few for himself. They savored each one and chased this meal, such as it was, with more water. They were still hungry, and it was hard not to eat the rest of the mushrooms on their way back to the balloon.

They were still walking when Khudabaksh turned to Bholanath and saw his friend’s temples form little spuds. The calf’s stubs lengthened all the way to proud, S-shaped horns. His pupils dilated and kept dilating until they filled his eyes, which had no whites left. Bholanath’s nostrils flared and kept flaring until a rough, off-pink tongue slithered out of his mouth and licked them. At this point, Bholanath mooed outright, terrifying Khudabaksh, who stumbled away with one hand and one wrist-stump thrust out at Bholanath. Backing away, he tripped over a log; he knocked his ankle and steadied himself, but fell onto his rear. “Ah!” he cried. When he sat up, he was straddling the log.

This black log, in Bholanath’s eyes, immediately sprang onto four feet, a small black horse. Khudabaksh’s hand held a burning book in it, obviously, from the way his Mussalmaan companion had shouted “Allah!”, the Qur’an. A pink gauze-strip dangling from his wrist lengthened and hardened into a blood-stained Mughal dagger with a mother-of-pearl hilt. Bholanath raised his own right arm out of reflex, to protect himself, and where his wrist-stump was, Khudabaksh saw a hoof. They both shouted, Khudabaksh for Allah’s help, Bholanath for Mahadev’s, and this only redoubled their terror of one another. For several minutes, they cowered behind oak trees fifty feet apart. Finally, they called across the distance.

“Khudabaksh?”

“Bhola?”

“Put that bloody dagger away, or I won’t talk to you!”

“First you put those horns back in your head!”

“Horns? What horns?”

Khudabaksh stuck his finger in his ear and toggled it smartly, eyes squinched. “Talk Gujarati, you shapeshifting Hindu! Stop that mooing!”

Bholanath looked around the tree and gasped. “First you whistle your Arabian over! He’s still glaring at me with his—with those eyes of his!”

“My Arabian?”

“The horse, you crazed old Mussalmaan!”

“Where?”

“Right there!”

“That’s a log, Bholanath!”

Bholanath put his fists to his eyes, rubbed hard, and looked again. “No, it’s definitely a horse. And now it’s lifting its tail and shitting fire. Take a look yourself if you don’t believe me.”

He retreated behind his oak and hugged his knees for warmth. To his surprise, his own knees had grown nipples that poked suggestively through the khaki. He stared, not particularly aroused, but mesmerized. The attempted dialogue stopped here for the next several minutes. On his end, Khudabaksh watched the mushroom-caps in his pocket inflate and subside rhythmically, like jellyfish breathing themselves along. Finally, when they exhaled for the last time, he checked back.

“Bholanath? Oy Bholanath!”

Bholanath peeked tentatively around his oak.

“See? I can talk to you now that you’ve put those horns back in your head.”

“Thanks for calling off your horse. What did you do with your Qur’an?”

“It’s in my pocket.”

“I mean the one that was on fire.”

“Who would dare burn a Qur’an? In a forest no less!”

Bholanath glimpsed the dangling gauze strip and rubbed his eyes again. No, it definitely wasn’t a dagger.

The two soldiers emerged tentatively, in their own shapes, no longer demonically transformed. They felt each other’s faces like blind friends meeting after a long time apart, and, satisfied, returned to the balloon together.

What happens next? You’ll have to read Soar to find out!