From love and loss, to survival and trauma – fiction brings out the human condition like no other space in literature. We love snuggling up with a good fictional story; there are so many characters to meet. And we especially love how a good story can take us through such an incredible range of emotions. There is nothing like screaming at your book because a character won’t stop being stupid, or jumping on our bed (you did not hear this from us) when those two people you had been rooting for over 300 pages finally get together.

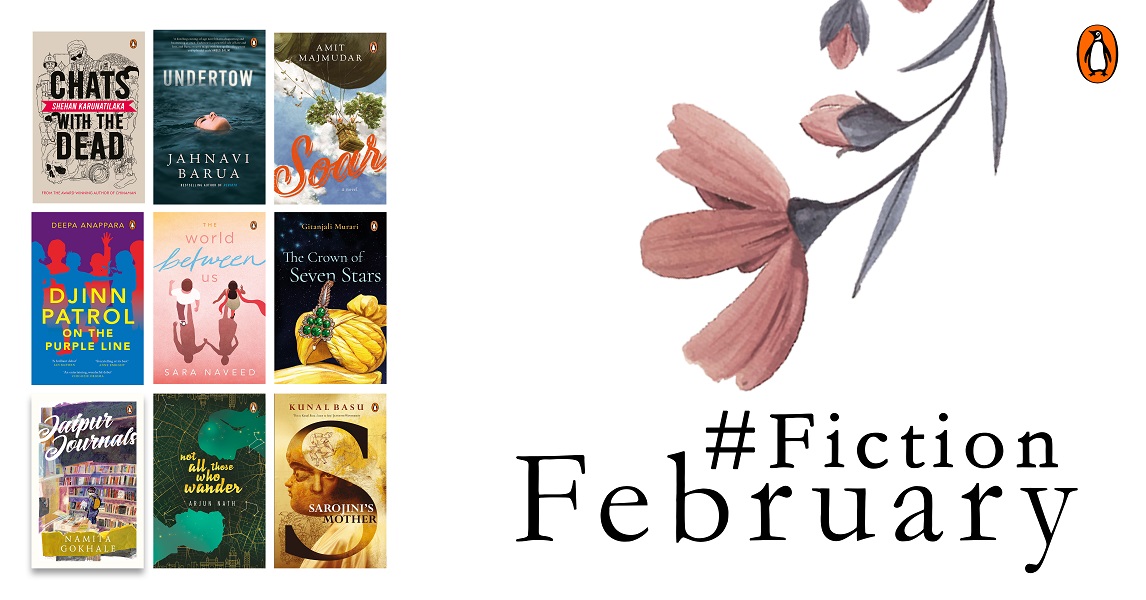

This February, we decided to take our reading passions a notch higher by celebrating the very singular experience reading fiction can give you. Our shelves this month is filled with as wide a range as the emotions these stories elicit. And we are giving you glimpses into just some of these worlds that we are stepping into.

It is time for #FictionFebruary, and we are (re)looking at some of the most poignant moments from our February stories that stayed with us long after we had turned the last page.

War, Memory, and Victimization

Chats with the Dead delve deep into the complexities and nuances of war and victimization. From all the voices from the afterlife we get to hear, this one really got us to stop for a moment.

‘If suicide bombers knew they end up in the same waiting room with all their victims, […] They may think twice.’

*

Writing the Rainbow

Alongside the rich cast of characters we get to meet in her worlds, Namita Gokhale has also given us some inspiring female characters who make us think on what it means to be a woman today. Her latest, Jaipur Journals, is no different, where we meet Zoya Mankotia, a celebrated writer making waves with her latest novel. In a panel, she speaks about the safety and freedom in writing that allows us to be who we are:

‘We can be who we are, write as we like. Sexuality, as a narrative, is a freeflowing river.’

*

Strength in Times of Trouble

Djinn Patrol is a powerful story of human warmth, resilience, and bravery that can emerge in times of trouble. We were hooked from the first page itself, with these lines:

‘When Mental was alive, he was a boss-man with eighteen or twenty children working for him, and he almost never raised his hand against any of them. Every week he gave them 5Stars to split between themselves, or packs of Gems, and he made them invisible to the police and the evangelist-types who wanted to salvage them from the streets, and the men who watched them with hungry eyes as the children hurtled down railway tracks, gathering up plastic water bottles before a train could ram into them.’

*

On Grieving the Right Thing

Sarojini’s Mother gives us a complex portrait of motherhood that goes well beyond just a biological concept. Sarojini confides in her friend Chiru about an abortion she went through because she was not ready to be a mother; and the confusing weight of grief that came with it:

‘Being right doesn’t take away the sadness, does it? I knew I’d lost again. I’d done to my baby what my mother had done to me. I’d kept the circle going. No matter how much I tried, I couldn’t stop myself from grieving. That’s when I knew I had to come to Calcutta.’

*

On Fighting the Sadness

We all try to deal with the weight of sadness in our day-to-day life. Seventeen-year-old Gehna’s words from Not All Those Who Wander on her simple but effective ways to fight her depression have definitely become our new strategy:

‘Wiser now, Gehna was no longer sure that she had any say in the comings and goings of the sadness, but she still held hope of ducking it. She had drawn strict boundaries, drip-feeding herself the pop songs about heartbreak and the tragic movies she loved, never exceeding a ratio of one part sad to nine parts happy.’

*

Too Much of A Good Thing

In Soar, we loved the friendship between soldiers Bholanath and Khudabaksh during World War I. It hit us hard when they realized and discovered the power and potential of greed in a dream-nightmare sequence:

‘Invited guests waited patiently as the pair added item after item to their infinite plate. This went on for hours in the dream—the soldiers smelling the food, acquiring the food, but never enjoying it. Eventually they realized that the abundance would never end, that abundance only enlarged appetite. So the dream revealed itself as a nightmare; and, at the same instant, they sat up.’

*

Moving On is Hard

Love and loss are very complicated things, and one of the hardest to move on from. We felt Amal’s pain in The World Between Us as she struggled to move on from her husband, Haider and her love for him. Reaching the point where she took the decision to move on made for one of the most powerful moments in her story:

‘It was true that I was still very much in love with Haider and his memories, but I was also beginning to realize that it was high time I moved on.

Life was so much more than a lifetime spent mourning and brooding on past memories.’

*

Unspoken Love

Family and home are two other things that can be beautiful and complicated all at once. One of the most powerful strands in Undertow is the simmering yet unspoken love between Loya and her estranged grandfather, Torun. Torun and his wife had thrown out Loya’s mother for marrying outside of her community. Twenty-five-year-old Loya returns to Torun and ends up reconnecting with him. This particular moment between the two of them carried exceptional emotional weight for us:

‘The girl then rose from her seat and came across to him.

She squatted and put her long arms across his shoulders. ‘I love you, I think, Koka.’

He watched her make her way back to her bedroom and drained the last of the amber liquid into his glass. He swallowed the last words, lest they escaped him.’

*

On Battles and Bravery

The Crown of the Seven Stars give us a powerful character in the form of Saahas (which means “bravery” in English) as he refuses to submit to oppression and tyranny that has taken over his Kingdom. The lines below are some of the many that translate internal battles into very external fights.

‘A blade whirling in each hand, Saahas roared like a summer storm and Zankroor came at him, braids tangling around his head like a white cobweb. Striking hard with his curved axe, he broke Saahas’s iron blade in half, the impact jolting Saahas to the ground. Zankroor swung the axe again, squealing in glee, and Saahas lunged, stabbing the broken blade into his adversary’s thigh, just above the knee, his other arm moving with lightning speed. Zankroor grunted. His axe whistled downwards, eager to meet Saahas’s neck. ‘

These lines and these characters brought us just a little bit closer to ourselves, and to life in general. Emotions and desires are never easy to figure out, but stories like these definitely help a little.

Which one of these are you going to pick up this month? Do share with us in the comments below!