The COVID-19 vaccine: a favourite topic in the present day. When will it arrive? Why are they taking so long? And most importantly, do we really need them, or is herd immunity enough in a country like ours?

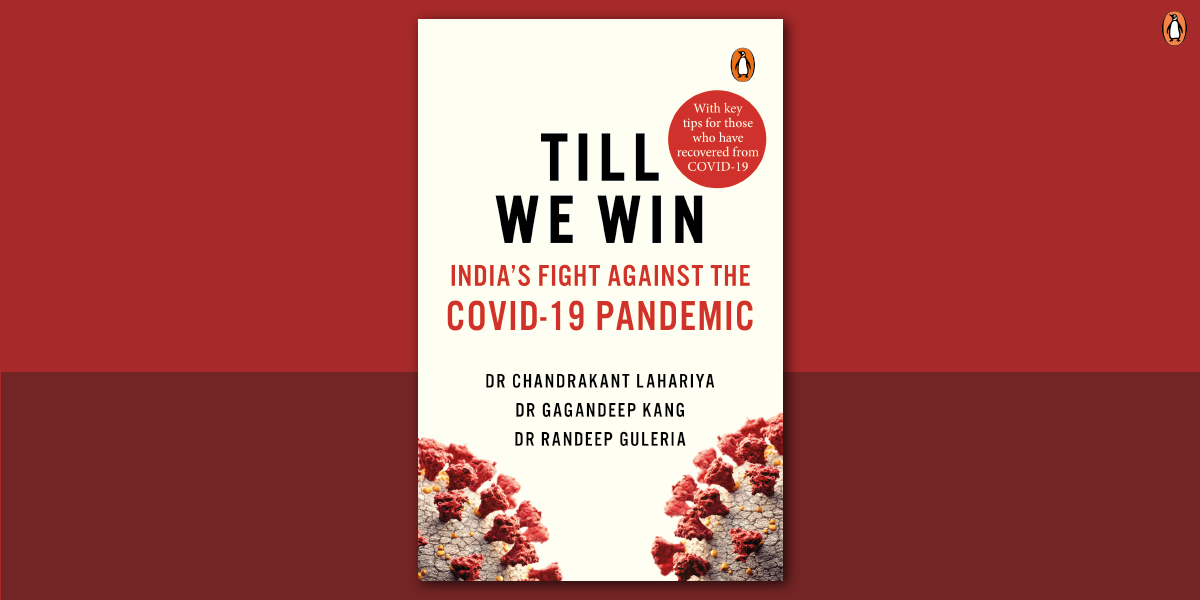

In this article we try and answer these questions, from Dr Chandrakant Lahariya, Dr Gagandeep Kang and Dr Randeep Guleria.

–

India is the largest producer (by volume or number of doses) of vaccines in the world, and provides vaccines to UNICEF which then distributes them in Africa, South America and Asia. For UNICEF to buy the vaccines, the vaccines have to be pre-qualified or approved for purchase by the WHO. The WHO’s approval process relies on the fact that the country which makes the vaccines has a national regulatory authority that meets the standards laid down by the WHO. India’s CDSCO has met these criteria and ensures that the vaccines made in India are of high quality and safe. Indian vaccine manufacturers, which have grown in number and capacity since they were established decades ago, have good and long experience with manufacturing in high volumes. However, they have only recently begun modest investments in research towards new vaccines. With a population of 138 crore, India needs local and indigenous production of the COVID-19 vaccine to ensure widespread availability.

The development and availability of the vaccine in India has been part of some of the early discussions on the country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. A national task force for vaccine research and development was set up in April 2020. The progress on the vaccines, both globally and in India, has been reviewed by high-level committees, and planning for delivery of the vaccines is ongoing. In early October 2020, the health minister announced a proposal to vaccinate 20 to 25 crore Indians by July 2021. In parallel with many such efforts around the world, discussions are on about the prioritization of target populations for initial vaccination.

When can we expect the first vaccine against COVID-19?

Till October 2020, six vaccines had been given limited licence in China and Russia. While a definite timeline is difficult to predict, there is a possibility that some vaccines may be available by early 2021. However, vaccination will be an ongoing process and it will be two to three years before sufficient vaccines are available to vaccinate all those in need.

There are a number of vaccines in the last stage of clinical trials, why is it taking so much time?

It is true that there are COVID-19 vaccines in phase III of clinical trials across the world, with trials starting in India. However, there are no guaranteed successes, and we need to wait for the results to know what works and what does not. If successful, the data need to be submitted to the regulatory authorities for approval. This is followed by production by one or more vaccine companies and then supply, resulting finally in availability. All these steps are expected to take some time.

What is herd immunity? Do we really need COVID-19 vaccines or is herd immunity enough?

Herd immunity is also called herd effect, community immunity, population immunity or social immunity. It is a form of indirect protection from infectious disease which happens when a defined proportion of the population has been infected and has become immune to an infection. As an increasing number of people are infected or vaccinated, the number of people who can be infected (‘susceptibles’) decreases and transmission or spread also decreases. When herd immunity is reached, it is important to note that this is a feature that works at the population level—a decrease in spread within a defined group; it is not perfect protection of all uninfected people. At the individual level, the status of immunity depends on that person’s exposure or vaccination status. This means that if a susceptible individual is no longer within the ‘herd’, then they are likely to be infected on exposure, and are not ‘immune’.

When the level of infection or vaccination that is required is calculated, then the basic reproductive rate of the virus has to be known. The higher the reproductive rate, the greater the proportion of the herd that needs to be infected or vaccinated to prevent the spread. For measles, which is very infectious, we would like to reach 95 per cent vaccination to prevent outbreaks. At this time, data from sero-surveys in India shows 7 per cent seropositivity in a national survey at the end of August but pockets of high positivity in urban areas (56 per cent in some localities in Mumbai and 51 per cent in areas of Pune and 29 per cent in Delhi). This indicates that herd immunity is still far for most of the country, and we should be looking to a vaccine for more predictable development of immunity.

–

Offering insights on how India continues to fight the pandemic, their book Till We Win is a must-read for everyone. It is a book for the people, for political leaders, policymakers and physicians, with the promise and potential to transform public health in India.