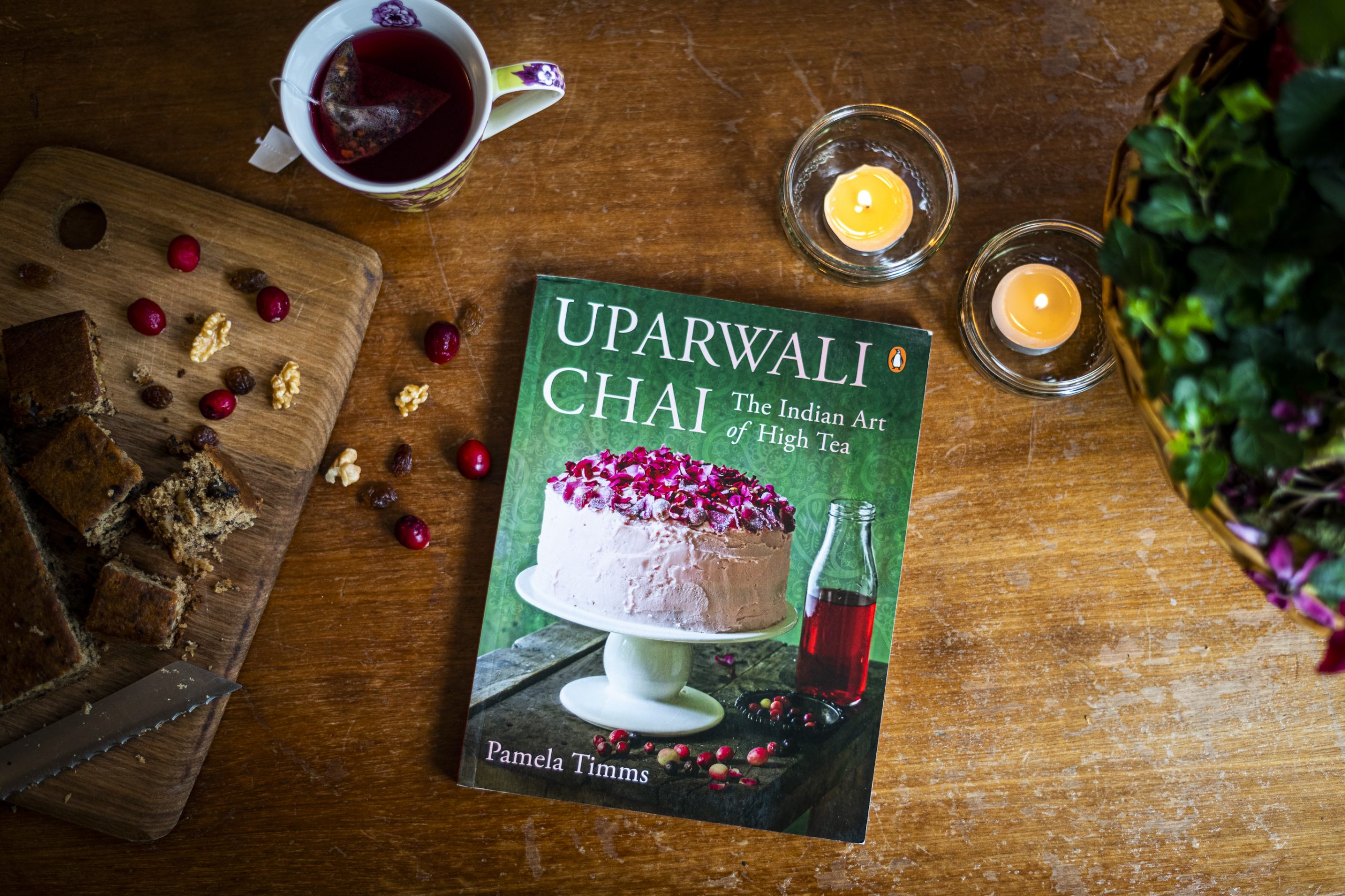

From Saffron and Chocolate Macarons to Apricot and Jaggery Upside Down Cake to a Rooh Afza Layer Cake, Uparwali Chai is an original mix of classic and contemporary desserts and savouries, reinvented and infused throughout with an utterly Indian flavour.

‘The recipes in this book reflect the baking I grew up with, the hug-in-a bowl fare of mothers, grandmothers and aunts.’- Pamela Timms, Author.

Check out this recipe from the book below:

Banana Loaf Cake with Chai-spiced Icing ( Serves 6-8 people)

For me[Pamela Timms], baking is a great stress buster, and in times of need I find I gravitate towards quite specific types of recipes. I’m not looking for complicated, fancy, lavishly decorated cakes. I want something that can be made quickly from a few kitchen staples but will yield something delicious and sustaining—that will help get me back on an even keel quickly.

Banana Bread is one such recipe, a faithful and comforting standby which can be rustled up at almost any time and is the cake equivalent of someone giving you a great big hug. The chai-flavoured icing is like the hugger giving you a bunch of flowers too.

Incidentally, cakes like this are called loaf cakes because they are usually baked in a loaf-shaped tin—you could, of course, use a round cake tin and bake for about 25 minutes.

For the cake:

250 g plain flour

2 tsp baking powder

½ tsp baking soda

½ tsp salt

125 g soft unsalted butter

175 g soft brown sugar

2 eggs, lightly beaten

1 tsp vanilla extract

400 g bananas, weighed without their skins (bananas that have gone a bit soft are ideal here)

For the chai-flavoured icing:

50 g icing sugar

1 tsp ground cinnamon

1 tsp ground cardamom

¼ tsp ground ginger

¼ tsp ground cloves

100 g soft butter

Splash of milk

You will need measuring scales, a 22 x 12 cm loaf tin and baking parchment.

- Preheat the oven to 180°C. Line a 22 x 12 cm loaf tin with baking parchment.

- Sift the flour, baking powder, baking soda and salt into a bowl and set aside.

- In another bowl, cream together the butter and sugar with an electric mixer or wooden spoon until pale and fluffy.

- Gradually mix in the eggs and vanilla extract, adding a little flour between additions to stop the mixture curdling.

- Mash the bananas in a bowl, then stir into the mixture.

- Finally, with a metal spoon, gently mix in the flour mixture.

- Spoon into the lined tin and level the surface a little. Bake in the centre of the oven for about 45 minutes or until the loaf has risen, is nicely browned and a skewer inserted in the middle comes out clean. Leave to cool.

- To make the icing, mix the icing sugar, spices and butter until soft and fluffy. When the cake is cool, cover the top with the icing.

The cake keeps well for a couple of days.

Uparwali Chai is the ultimate teatime cookbook, with an Indian twist. The book is available now.