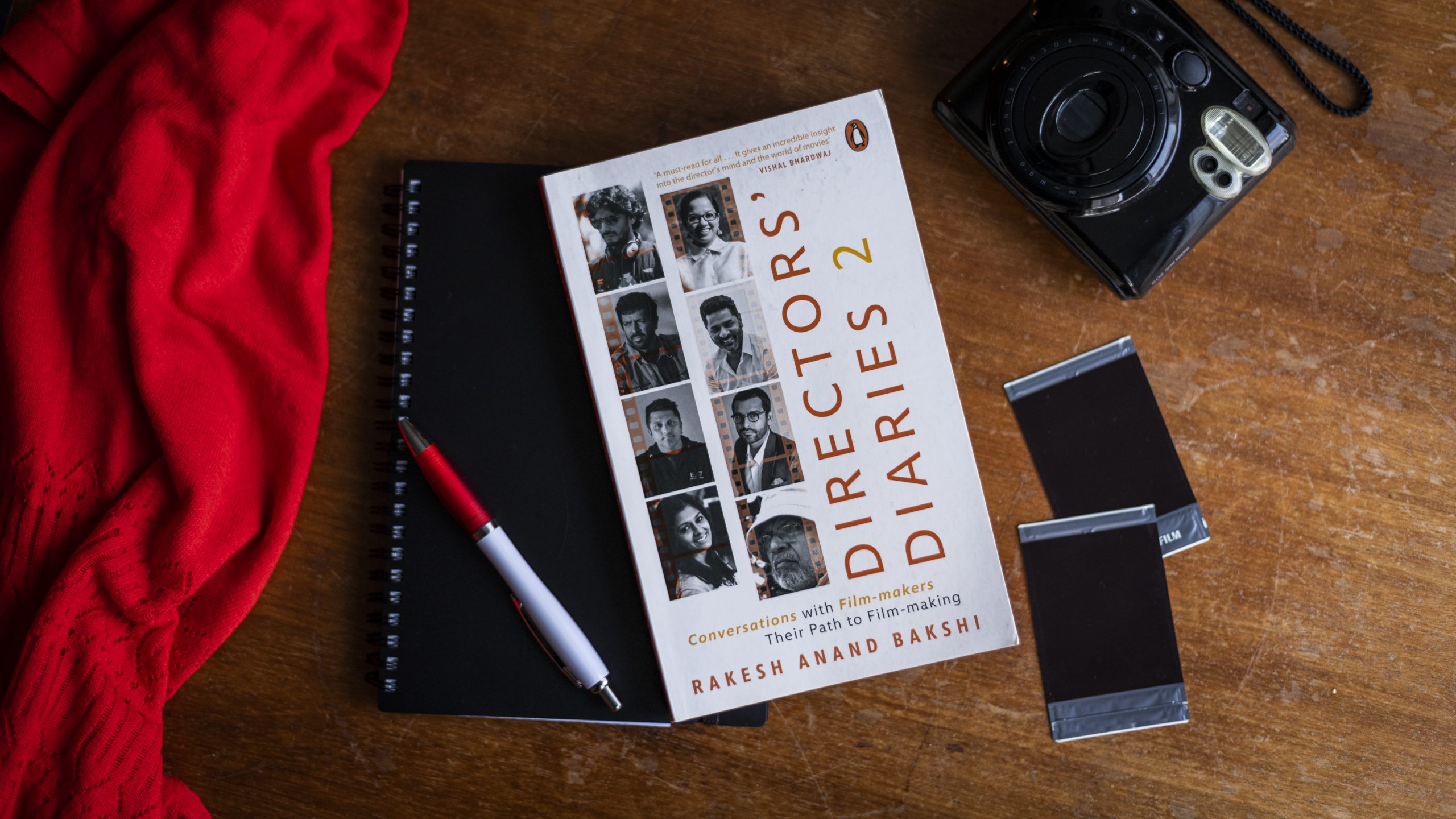

With Directors’ Diaries 2, Rakesh Anand Bakshi adds yet another volume to his ongoing series of conversations with Hindi cinema’s most iconic voices. This time he shares with us his conversations with some of the industry’s most eminent film-makers as well as significant but often overlooked behind-the-scenes crew such as spot boy Salim Shaikh, make-up artist Vikram Gaikwad and sound designer Rakesh Ranjan.

Read on to get a look at the workings of the behind-the-scenes crew of a movie:

Spot boys have feelings too!

Few people address us [spot boys] by our names. We like it when they [film crew] address as a Spot Dada, but it feels great when we know that they know our names. We spot boys do many odd jobs in the long chain of film-making and are largely unnoticed and sometimes appreciated by the crew. People who watch films are unaware of our work and our significance on the film set. Even the people who handle lights and the settings department have greater visibility than us.

Spot boys are the foundation of film-making

According to me [Spot Boy Salim Shaikh], spot boys, light men and the settings department lay the foundation every day in film-making. These three departments together help the unit set up a shoot every day and clear things post pack-up, when all the technicians, actors, cinematographer, producer, director, have gone home. We stay around for at least two more hours after everyone has left and arrive an hour or two before the others. Yet, we are paid only for the duration of our fixed shifts and never for overtime.

Make-up Artists Know Best!

The job of a make-up artist is not only to apply make-up but to also tell directors when it is required and when it is not. Unfortunately, many actors, especially females, and directors do not understand or appreciate this. They force us to apply make-up even when it is not required. For example, if you want a young girl to look like a mature woman, simply apply a lot of make-up. But, if the aim of the story is to retain the innocence and youth of the character, by forcing me [Make-up Designer Vikram Gaikwad] to apply too much make-up, the actor or director is going against the essence of the character.

If you’re working with prosthetics, too much heat is a problem!

The craft of prosthetic make-up is a nightmare in India because of the heat and humidity. Prosthetics are usually created by the application of foam pieces or silicon rubber pieces over the skin. For the foam or skin-safe silicone rubber to stick to the skin, we use a ‘medical’ gum—a paste that is skin-safe. The problem that arises is that the sweat from the heat or humidity dissolves the medical gum, thus weakening the bond between the skin and the moulding.

The sound designer is a very effective storyteller

Yes! The sound man is a very effective storyteller. He has to his disposal the various elements of the narrative—such as the dialogue, location ambiences, foleys, BGM and most importantly, silences—all of which constantly manipulate the audience’s perception of the story along with the visuals and the visual edits. I [Sound Designer Rakesh Ranjan] consider the sound textures as themes, because the tonal quality of all the sounds plays a very important part in the narrative, and this varies from subject to subject. I create sound texture by working on the tonal quality of the actor’s voice, their footsteps, and other foley sounds.

Aspiring directors, book lovers and cinema fans should grab their copies Directors’ Diaries 2 today!