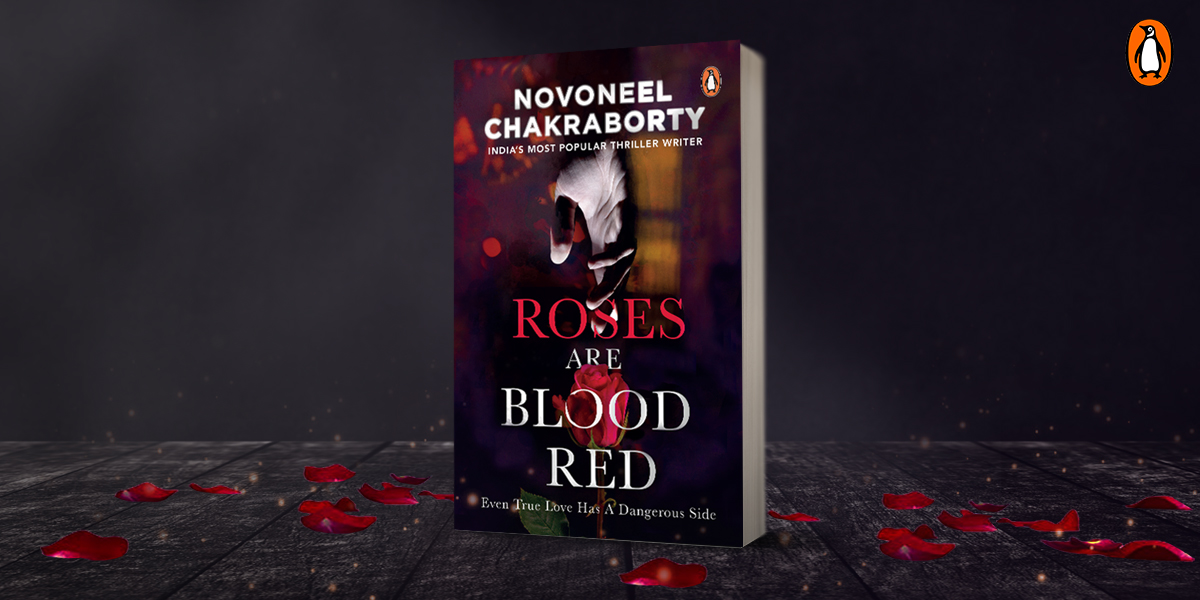

‘I’ll gift you a love story that every girl desires, but few get to live.’

He’d told me once. And boy, did he stick to his words! Vanav Thakur is the perfect boyfriend that any girl can have. Sometimes, I wonder if I really deserve him.

I’m Aarisha Shergill and my life is about to get ripped apart because I should have known some things should be left alone.

Bestselling author Novoneel Chakraborty is back with Roses Are Blood Red. Read the prologue from the book below:

—

TOSH, HIMACHAL PRADESH Sometime Ago

It was an important day for her. Very important. He was coming down to meet her after . . . in fact, she had been counting: three months, fifteen days, eleven hours and—as she left her house—exactly nine minutes. She had told her parents that she would stay with her bestie from college— Pragya—that night. Pragya, obviously, had no idea about her subterfuge.

He had selected the venue for their clandestine meet. It was only two blocks from her house to the small tea shop that would have closed for the day by then.

Despite the several layers she had on, Aarisha’s teeth chattered as she cycled towards the tea shop. The shiver was partially due to the unseasonal cold wave that had gripped the Himalayan town; she trembled more in anticipation of the impending rendezvous. Should I launch into his arms as soon as we meet? Or should I stand back and simply admire him for a bit? With an avalanche of thoughts crashing through her mind, she finally reached the location for their tryst. She stopped nineteen-to-the-dozen. Only the rarest find their harmony in silence. They were rare, she knew.

She cupped his jaw in her long-fingered hands and caressed his three-day-old stubble with her thumbs. He stretched out an arm to flick the switch on the car stereo. Ariana Grande’s husky voice softly permeated the interior of the car with one of her favourite tracks: ‘God is a Woman’. Aarisha leaned in, but before their lips could touch, he gripped her waist and stopped her descent.

‘Not so quick, Ranisa,’ he whispered.

She loved it when he called her by that name. ‘Ranisa’ meant queen—his queen.

If there was one thing she absolutely loved and couldn’t quite define, it was his enormous respect for her. It was so deep-seated that she often wondered whether she deserved to be placed on such a high pedestal.

‘You always say this,’ she whispered petulantly. ‘Don’t you want to kiss me?’

He stared at her beauty, her dark hair cascading like a cloud around her shoulders. Her eyes didn’t reflect pain, they carried a complaint.

‘D’you honestly believe that I don’t want to kiss you?’ he asked.

‘Then why don’t you?’ she sulked. ‘Also,’ she dismounted from him and scrambled back into her seat, ‘I hate it when you leave me and go away.’ He sensed the flood of tears about to burst through the dam at any moment.

‘Why?’ he asked softly.‘I feel insecure about you, about us,’ Aarisha choked.

An ironical smile touched his face. ‘You know this thing we call love, it’s like a dense forest. As you enter, you hear the growl of several wild beasts. At times, you may even encounter them. Insecurity is the most ferocious beast in this jungle. Whether to fall victim to it or vanquish it to continue one’s quest to unearth the greatest treasure ever, which is also hidden in this very forest, is the lover’s call. I’ve taken mine. What’s your call, Ranisa?’

She stared at him, amazed at the total conviction in his eyes. How could someone’s eyes always reflect such confidence? It was the kind of assurance one developed after scrutinizing life so closely that its tricks became only too predictable. She leaned over and kissed his closed eyelids.

‘I’ll fight. I promise I’ll fight all the beasts that come our way,’ she whispered.

There was a faint smile on his face as he said, ‘Don’t worry about the distance between us.’ He raised her downcast face and kissed her forehead, ‘The body is only what is. The soul is what is, what was and what will be. The scope of all the urges stemming from the body is a mere molecule compared to the intense longing that arises from the soul. And for the soul, distance is an alien concept. Distance only restricts the body.’

‘But the body is also important in its own way, isn’t it?’

‘As much as a house of bricks and mortar, because it houses the vulnerable and the fragile within. But we all know that the shelter is temporary and, as all temporary things, too transient to worry about.’

‘What’s permanent then?’ Aarisha asked.

He placed his right hand flat against her left hand, palm to palm, their fingertips splayed until they found the gaps through which the fingers slipped, and the hands clasped each other.

‘This,’ he said, tightening the clasp, ‘this is permanent.’

I wish I could tell you the number of wars I’ve fought to make this permanent, he thought.

‘D’you know, there are times in your absence when I get the feeling that I hardly know you at all. Is that good?’ she asked, resting her head on his shoulder.

‘You’ll know. You’ll know very soon. It’s just a matter of one more year.’

‘One more year?’ she asked, frowning.

‘Yes. In one more year I’ll gift you a love story that every girl desires, but few, if any, get to live,’ he whispered.

‘What do you mean?’ she drew back to look at his face. There was no response. She raised her head—and suddenly she felt a tug on her hair.

‘Ouch!’ she yelled. Before she realized what was happening, she felt a punch on her face that broke her nose and lacerated her lips. The second punch that buried itself in her gut almost made her throw up. Aarisha fell unconscious, her face a bloodied mess. Three more punches followed: one to her jaw, another landed in her ribs and the third, in the stomach again. He shoved her away from him with force. The side of her head slammed against the window. He yanked down her jeans, slipped them off her legs and tossed them out of the window. He tugged her panties down to her knees and from his pocket he extracted a vial of semen. He smeared

some of the semen on her panties, on her dress and emptied the rest on her bare abdomen. He made sure nobody would ever track down whose semen it was. For a doctor, it wasn’t even a task. He dressed her back in a hasty manner.

As soon as he was done, he used his cell phone to call the local police station. Emotionlessly, he relayed the information, ‘A girl has been raped and abandoned on the road.’ He gave them the approximate location before hanging up. He glanced at Aarisha’s unconscious battered face and muttered, ‘The first thing you should know about me is: I…Don’t…Let…Go…’

He turned on the ignition, opened the passenger side door and pushed the girl’s insensate body out. He put the car into gear, gunned the engine and sped away into the night. After half an hour of driving, he stopped. He alighted from the car and stood at the edge of the abyss, gazing into the darkness. He dialled the police again. They informed him that the girl had been rescued and countered with their own questions about his identity. In reply, he flung the phone into the abyss as far as it would go. He looked up at the night sky— at the constellations of stars—they had mocked him enough. They thought she would never be his. And now, he would win her from everything—and everyone.

He extended both his middle fingers skywards and bellowed a bloodcurdling war-cry against destiny.

Vanav Thakur was no ordinary man. He was soul-deep in love with a girl. And he was a man with a plan.

Curious to know what happens next? Mysteriously thrilling in its essence, Novoneel Chakraborty’s Roses Are Blood Red is a haunting story of a passionate and eternal love.