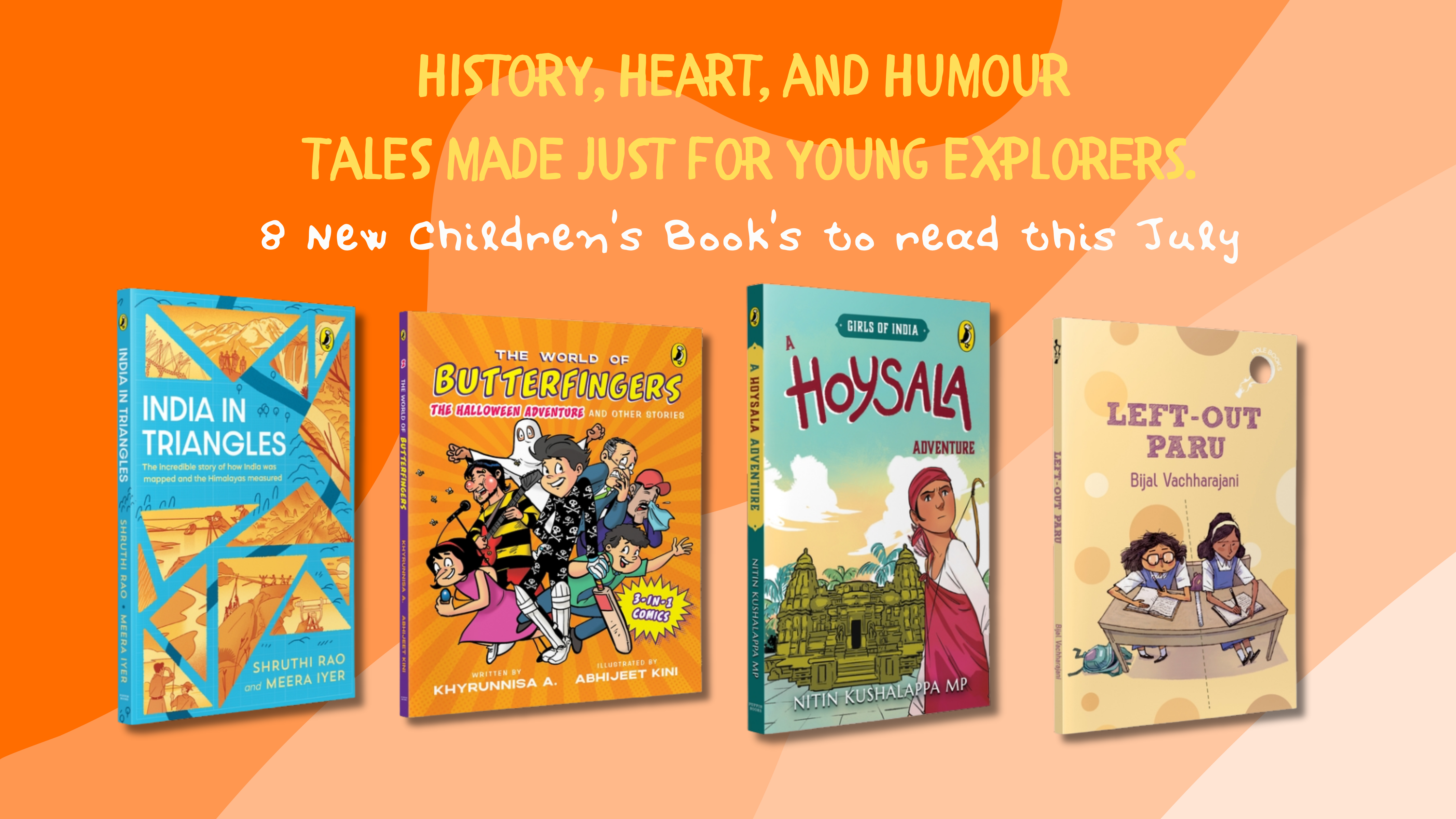

नई उमर की नई फसल 2025 : कलम से किताब तक

युवा आवाज़ के लिए कहानी लेखन प्रतियोगिता

क्या आप 18 से 27 वर्ष के बीच हैं? क्या आपके भीतर कोई कहानी है जो दुनिया से साझा की जानी चाहिए? अबआपके पास मौका है कि आपकी कहानी पेंगुइन स्वदेश और अमर उजाला फाउंडेशन के साथ प्रकाशित हो!

हमें घोषणा करते हुए बेहद प्रसन्नता हो रही है — “नई उमर की नई फसल 2025 – कलम से किताब तक“, एकअनोखी कहानी प्रतियोगिता जिसमें अगली पीढ़ी के कहानीकारों को आमंत्रित किया जा रहा है कि वे अपनी आवाज़, दृष्टिकोण और कल्पना को दुनिया के सामने लाएँ।

प्रतियोगिता की मुख्य जानकारी :

महत्त्वपूर्ण तिथियाँ:

•प्रतियोगिता की घोषणा : 20 जुलाई 2025 व अंतिम तिथि : 5 अगस्त 2025

• चयनित कहानी की घोषणा : 20 अगस्त 2025

प्रतियोगिता का उद्देश्य क्या है?

प्रतिभागियों को आमंत्रित किया जाता है कि वे 2000-2500 शब्दों के बीच अपनी मौलिक लघु कहानियाँ हिंदी मेंभेजें। आप इन विषयों जैसे जीवन, रिश्तों, कॉलेज, सपनों, डर, पहचान, बचपन, विज्ञान–कथा या किसी सच्ची घटनापर लिख सकते हैं — कोई भी कहानी जो आपकी अलग आवाज़ और दृष्टिकोण को दर्शाए।

अगर आप विजेता बनते हैं तो क्या मिलेगा?

•चुनी गई कहानियाँ पेंगुइन स्वदेश द्वारा एक संग्रह के रूप में प्रकाशित होंगी।

•विजेताओं को प्रकाशन अनुबंध पर हस्ताक्षर करने होंगे।

•अमर उजाला आपकी कहानी को अपने प्रिंट और डिजिटल प्लेटफॉर्म पर कवर करेगा।

•आपकी रचना अमर उजाला के प्रकाशनों में समीक्षित और सम्मानित की जायेगी।

•प्रकाशित पुस्तक पर अमर उजाला का नाम और आपका नाम सदा के लिए अंकित होगा।

योग्यता:

•आयु : 18 से 27 वर्ष

•भाषा : हिंदी

•केवल मौलिक रचनाएँ मान्य होंगी (नकल की गई सामग्री अस्वीकार की जाएगी)

•चयनित प्रतिभागियों को वैध आयु प्रमाण और अनुबंध पर हस्ताक्षर करना अनिवार्य होगा।

आवेदन कैसे करें?

20 जुलाई 2025 से पेंगुइन स्वदेश व अमर उजाला की आधिकारिक वेबसाइट/सोशल मीडिया पर उपलब्ध लिंक/ई-मेल पर जाकर अपनी कहानी अपलोड करें।

यह प्रतियोगिता अमर उजाला शब्द सम्मान पहल का हिस्सा है, जो भारतीय भाषाओं में लेखन का उत्सव मनाती है।यह पहल पेंगुइन स्वदेश — पेंगुइन रैंडम हाउस इंडिया की एक इकाई — के सहयोग से आयोजित की जा रही है, जिसका उद्देश्य स्थानीय प्रतिभाओं और भाषाओं को प्रोत्साहन देना है।

हम मिलकर एक ऐसा मंच बना रहे हैं जो आज के उभरते हुए कहानीकारों को कल के प्रकाशित लेखक बनने काअवसर देता है।

लिखिए, साझा कीजिए, और अपनी कहानी को किताब बनने दीजिए। क्योंकि जो आप लिखते हैं — वह एकअनोखी किताब बन सकती है।

________________________________________

❓ अक्सर पूछे जाने वाले सवाल और सबमिशन गाइडलाइन्स (FAQs & Submission Guidelines)

• प्रश्न: कौन भाग ले सकता है?

उत्तर: 18 से 27 वर्ष की आयु (31 जुलाई 2025 तक) वाले युवा भाग ले सकते हैं। चयनित प्रतिभागियों को वैधआयु प्रमाण देना अनिवार्य होगा।

• प्रश्न: कौन–सी भाषाओं में प्रविष्टियाँ स्वीकार की जायेंगी?

उत्तर: केवल हिंदी में लिखी गई कहानियाँ मान्य हैं।

• प्रश्न: मुझे किस विषय पर लिखना है?

उत्तर: विषय पूर्णतः खुला है — जीवन, दोस्ती, पहचान, कॉलेज, यादें, डर, सपने, विज्ञान–कथा, सच्ची घटनाएँ याजो भी आपको प्रेरित करे।

• प्रश्न: शब्द सीमा क्या है?

उत्तर: आपकी कहानी 2000 से 2500 शब्दों के बीच होनी चाहिए।

• प्रश्न: क्या मैं एक से अधिक कहानियाँ भेज सकता/सकती हूँ?

उत्तर: नहीं, प्रति प्रतिभागी केवल एक ही प्रविष्टि मान्य है। एक से अधिक भेजने पर अयोग्य घोषित कर दियाजाएगा।

• प्रश्न: अंतिम तिथि क्या है?

उत्तर: प्रविष्टियाँ भेजने की अंतिम तिथि 5 अगस्त 2025 है।

• प्रश्न: कहानी कैसे भेजें?

उत्तर: प्रतियोगिता पोस्टर पर दिए गए ई-मेल या हमारी आधिकारिक वेबसाइट/सोशल मीडिया पर 20 जुलाई 2025 से उपलब्ध लिंक पर जाकर कहानी अपलोड करें।

• प्रश्न: अगर मेरी कहानी चयनित होती है तो क्या होगा?

उत्तर: चयनित कहानियाँ पेंगुइन स्वदेश द्वारा संपादित और प्रकाशित की जायेगी। लेखक को एक प्रकाशन अनुबंधपर हस्ताक्षर करना होगा और अमर उजाला द्वारा उनकी रचना को कवर किया जाएगा।

• प्रश्न: क्या मैं पहले से प्रकाशित कहानी भेज सकता/सकती हूँ?

उत्तर: नहीं। केवल मौलिक और अप्रकाशित कहानियाँ ही स्वीकार की जायेंगी। कॉपी की गई या पहले प्रकाशितकहानियाँ अयोग्य घोषित कर दी जायेंगी।

________________________________________

नियम और शर्तें

नई उमर की नई फसल : कलम से किताब तक

ये नियम, शर्तें और दिशानिर्देश (“नियम”) “नई उमर की नई फसल : कलम से किताब तक प्रतियोगिता” (“प्रतियोगिता”) पर लागू होते हैं और इसका संचालन पेंगुइन रैंडम हाउस इंडिया प्राइवेट लिमिटेड (“PRHI”/ “हम”) द्वारा इसके प्रचार साझेदार अमर उजाला लिमिटेड (“अमर उजाला”) के साथ मिलकर किया जा रहा है।

यदि आप प्रतियोगिता में भाग लेते हैं तो यह माना जाएगा कि आप इन नियम व शर्तों से पूरी तरह सहमत हैं :

PRHI को बिना पूर्व सूचना के इन नियमों में बदलाव करने का अधिकार सुरक्षित है। प्रतिभागियों को सलाह दी जाती हैकि वे इन नियमों की समय-समय पर समीक्षा करते रहें। यदि आप किसी भी नियम या उसमें किए गए किसी भी संशोधनसे असहमत हैं, तो कृपया प्रतियोगिता में भाग न लें। प्रतियोगिता में भाग लेना पूर्णतः वैकल्पिक और स्वैच्छिक है।

1.

जो व्यक्ति प्रतियोगिता में भाग लेना चाहते हैं (“प्रतिभागी”/ “आप”), उन्हें 2000 से 2500 शब्दों के बीच हिंदी भाषा मेंस्वयं द्वारा लिखी गई एक मौलिक कहानी (“प्रविष्टि”/ “प्रविष्टियाँ”) भेजनी होगी।

निर्धारित शब्द सीमा से बाहर की गई किसी भी प्रविष्टि को अयोग्य घोषित कर दिया जाएगा।

2.

प्रविष्टियाँ 5 अगस्त 2025 (“अंतिम तिथि”) तक दिए गए ईमेल के माध्यम से जमा की जानी चाहिए। इस तिथि केबाद भेजी गई या किसी अन्य ईमेल या पते पर भेजी गई प्रविष्टियाँ स्वीकार नहीं की जाएँगी।

3.

प्रतियोगिता में भाग लेने वाले सभी प्रतिभागियों की आयु अंतिम तिथि तक 18 वर्ष या उससे अधिक होनी चाहिए। यदिकोई प्रतिभागी अंतिम तिथि पर 18 वर्ष से कम आयु का पाया गया, तो उसे अयोग्य घोषित कर दिया जाएगा।

4.

सभी प्रविष्टियाँ मौलिक और पहले से अप्रकाशित होनी चाहिए। यदि कोई प्रविष्टि कहीं भी प्रकाशित पाई जाती है यानकल की गई है, तो वह अयोग्य मानी जाएगी।

5.

प्रत्येक प्रतिभागी केवल एक ही प्रविष्टि जमा कर सकता/सकती है। यदि किसी प्रतिभागी द्वारा एक से अधिक प्रविष्टियाँभेजी जाती हैं, तो केवल पहली प्रविष्टि पर ही विचार किया जाएगा।

प्रतियोगियों को सलाह दी जाती है कि वे अलग-अलग ईमेल पतों का उपयोग करके एक से अधिक प्रविष्टियाँ न भेजें।केवल प्राप्त पहली प्रविष्टि पर ही विचार किया जाएगा और आपके वैकल्पिक ईमेल पतों से भेजी गई अन्य प्रविष्टियों कोप्रतियोगिता में शामिल नहीं किया जाएगा।

एक बार प्रविष्टि भेजे जाने के बाद, उसे बदला या हटाया नहीं जा सकता।

यदि कोई प्रविष्टि दो लोगों द्वारा मिलकर लिखी गई है, तो उनमें से कोई भी व्यक्ति किसी अन्य प्रतिभागी के साथ एकऔर प्रविष्टि (एकल या संयुक्त) नहीं भेज सकता/सकती।

6.

यदि दो प्रतिभागी मिलकर एक प्रविष्टि संयुक्त रूप से प्रस्तुत करते हैं, तो दोनों प्रतिभागियों का इन नियमों के अनुसारपात्रता होनी आवश्यक है।

7.

PRHI उन प्रविष्टियों की कोई ज़िम्मेदारी नहीं लेता जो खो जाती हैं, विलंबित होती हैं, गलत पते पर भेज दी जाती हैं, अधूरी होती हैं या तकनीकी अथवा अन्य कारणों से प्राप्त नहीं हो पातीं। सिर्फ ईमेल भेजना या सोशल मीडिया पर सीधेमैसेज करना इस बात का प्रमाण नहीं है कि हमें आपकी प्रविष्टि प्राप्त हो गई है। सिर्फ वही प्रविष्टियाँ मान्य होंगी जोनिर्धारित माध्यम (लिंक या क्यूआर कोड या ईमेल) के माध्यम से भेजी गई हों। किसी अन्य माध्यम से भेजी गई प्रविष्टियाँअमान्य मानी जाएँगी।

8.

PRHI और अमर उजाला के कर्मचारी, पूर्णकालिक सलाहकार या निदेशक, एवं उनके परिवार के सदस्य/ घर के सदस्यया उनकी सहायक/संबद्ध कंपनियों, एजेंसियों आदि के कर्मचारी प्रतियोगिता में भाग लेने के पात्र नहीं हैं।

9.

PRHI सभी योग्य प्रविष्टियों की समीक्षा करेगा और अपने विवेकानुसार प्रविष्टियों का चयन करेगा, जिन्हें एक संकलन मेंप्रकाशित किया जाएगा। चयन का आधार कहानी की साहित्यिक योग्यता, शैली, भाषा और सामान्य उपयुक्तता परआधारित होगा। ये सभी मानदंड PRHI की स्वनिर्धारित प्रक्रिया के अनुसार होंगे।

10.

चयनित प्रतिभागियों की आयु, पहचान और पता सत्यापित किया जाएगा। इन नियमों को स्वीकार करके आप सहमतिदेते हैं कि आवश्यकता पड़ने पर आप ऐसे दस्तावेज़ प्रस्तुत करेंगे जो आपकी पहचान, आयु और पते की पुष्टि करते हों।

11.

यदि सत्यापन प्रक्रिया के बाद कोई प्रविष्टि प्रकाशन योग्य पाई जाती है, तो PRHI स्वयं उस प्रतिभागी से संपर्क करेगाऔर प्रकाशन अनुबंध (पब्लिकेशन कॉन्ट्रैक्ट) के लिए प्रक्रिया आगे बढ़ाएगा।

12.

कोई भी प्रविष्टि केवल तभी प्रकाशित की जाएगी जब संबंधित प्रतिभागी और PRHI के बीच एक औपचारिक अनुबंधकिया गया हो।

13.

PRHI को यह अधिकार प्राप्त है कि वह किसी भी प्रविष्टि में प्रकाशन से पूर्व संपादकीय परिवर्तन कर सके। यदिसंबंधित प्रतिभागी इन संपादकीय परिवर्तनों से सहमत नहीं होता, तो PRHI को उस प्रविष्टि को प्रकाशित न करने काअधिकार होगा।

14.

प्रविष्टियों के चयन, पात्रता और प्रकाशन-योग्यता पर PRHI का निर्णय अंतिम और सभी प्रतिभागियों के लिए मान्यहोगा। PRHI को यह अधिकार प्राप्त है कि वह किसी भी प्रविष्टि को किसी भी चरण पर अस्वीकार कर सकता है—चाहेवह विचार हेतु हो या प्रकाशन हेतु हो।

PRHI और अमर उजाला किसी भी पक्ष द्वारा प्रतियोगिता की प्रक्रिया, चयन या शॉर्टलिस्टिंग, या किसी भी अन्य पहलूसे संबंधित किसी भी प्रकार की पूछताछ या प्रश्नों का उत्तर देने के लिए बाध्य नहीं होंगे।

15.

जब प्रकाशन के लिए प्रविष्टियाँ अंतिम रूप से चयनित हो जाएँगी, तो PRHI और अमर उजाला, संबंधित प्रतिभागियों सेप्रतियोगिता से जुड़ी प्रचारात्मक गतिविधियों में भाग लेने का अनुरोध कर सकते हैं। इसमें वीडियो में भाग लेना औरअपनी तस्वीरें उपलब्ध कराना शामिल हो सकता है। PRHI, अपनी इच्छा से, चयनित प्रतिभागियों की छवियाँ उसपुस्तक में भी प्रकाशित कर सकता है।

इन नियमों को स्वीकार करके प्रतिभागी यह स्पष्ट सहमति देते हैं कि वे अपनी व्यक्तिगत तस्वीरें और वीडियो PRHI औरअमर उजाला के साथ इस प्रतियोगिता के लिए साझा करेंगे।

16.

इन नियमों को स्वीकार करके प्रतिभागी आगे यह सहमति देते हैं कि PRHI और अमर उजाला उनके नाम, उम्र और ईमेलपते जैसे विवरणों को प्रतियोगिता के अलावा भी, जैसे कि सामान्य मार्केटिंग और प्रचारात्मक उद्देश्यों के लिए, संग्रहितऔर उपयोग कर सकते हैं।

17.

प्रतिभागी यह समझते और स्वीकार करते हैं कि जो व्यक्तिगत डेटा उन्होंने PRHI और अमर उजाला के साथ साझा कियाहै, उसे भारत के क्षेत्रीय अधिकार-क्षेत्र से बाहर होस्ट किए गए कंप्यूटर सिस्टम्स पर प्रोसेस किया जा सकता है।

यह प्रक्रिया PRHI और अमर उजाला की सूचना-प्रौद्योगिकी और सूचना-सुरक्षा प्रणालियों के अनुसार आवश्यक होसकती है, और प्रतियोगिता से जुड़े उनके दायित्वों को पूरा करने हेतु भी आवश्यक है।

“व्यक्तिगत डेटा की प्रोसेसिंग” का अर्थ है—व्यक्तिगत जानकारी पर किया गया कोई भी कार्य, जैसे कि उसका संग्रहण, रिकॉर्डिंग, संरचना, भंडारण, संशोधन, उपयोग, संयोजन, प्रेषण, सार्वजनिक रूप से उपलब्ध कराना, सीमित करना, मिटाना या नष्ट करना।

18.

प्रतिभागी यह स्वीकार करते हैं कि वे PRHI, अमर उजाला, उनके निदेशकों, कर्मचारियों, अधिकारियों, एजेंटों याप्रतिनिधियों को किसी भी प्रकार के दावे, हानि, मांग, लागत, क्षति, निर्णय, खर्च या देनदारी (जिसमें यथोचित कानूनीखर्च भी शामिल है) से सुरक्षित और मुक्त रखेंगे—जो उनकी प्रविष्टि के सबमिशन के परिणामस्वरूप उत्पन्न हो सकते हैं।

19.

यदि कोई प्रतिभागी इन निर्धारित नियमों का उल्लंघन करता हुआ पाया जाता है, तो PRHI को यह अधिकार प्राप्त है किवह उस प्रतिभागी को प्रतियोगिता से अयोग्य घोषित कर दे और आवश्यकतानुसार उचित कानूनी कार्रवाई भी करे। इसमें(परंतु केवल इन्हीं तक सीमित नहीं) PRHI की प्रतिष्ठा को हुई क्षति या अनुबंध के उल्लंघन के लिए हर्जाने या क्षतिपूर्तिकी मांग भी शामिल हो सकती है।

20.

इस प्रतियोगिता और उससे संबंधित सभी नियमों के संदर्भ में PRHI का निर्णय अंतिम, मान्य और गैर-विवादास्पदहोगा। इस विषय में किसी भी प्रकार की चर्चा या पत्राचार स्वीकार नहीं किया जाएगा।

21.

इस प्रतियोगिता से संबंधित किसी भी प्रकार के विवाद की स्थिति में केवल भारत के कानूनों का पालन किया जाएगा, और ऐसे किसी भी विवाद में केवल दिल्ली के न्यायालयों को विशेष क्षेत्राधिकार प्राप्त होगा।