Nothing says new year like a dazzling list of books brimming with enchanting stories of lands far and near. In the spirit of new beginnings, we are back with a diverse list of books for young readers. We hope that you’ll find something here for your child that they would cherish and hold dear for a long time to come.

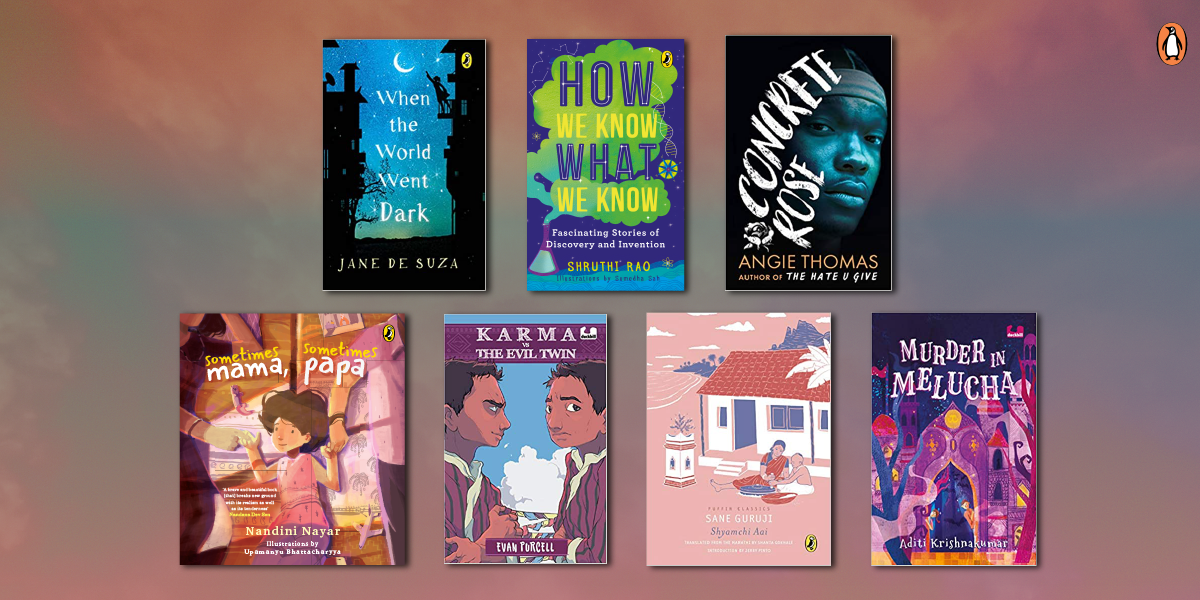

Murder in Melucha

Aditi Krishnakumar

In Melucha, children’s alphabet books teach that H is for hemlock, so it is no particular surprise when someone is found murdered. But in a city where everyone has devious and twisted motives, and dire plans, it is not easy for Meenakshi and Kalban to find the murderer.

In this sequel to the acclaimed The Magicians of Madh, Aditi Krishnakumar pulls off another delightful romp, full of mystery, humour and hilarious predicaments.

Concrete Rose

Angie Thomas

With his King Lord dad in prison and his mom working two jobs, seventeen-year-old Maverick Carter helps the only way he knows how: slinging drugs. Life’s not perfect, but he’s got everything under control. Until he finds out he’s a father…

Suddenly it’s not so easy to deal drugs and finish school with a baby dependent on him for everything. So when he’s offered the chance to go straight, he takes it. But when King Lord blood runs through your veins, you don’t get to just walk away.

From international phenomenon Angie Thomas comes a hard-hitting return to Garden Heights with the story of Maverick Carter, Starr’s father, set seventeen years before the events of the award-winning The Hate U Give.

Shyamchi Aai

Sane Guruji, Shanta Gokhale (tr.)

The evening prayers in the ashram are over. Cowbells tinkle sweetly in the distance. The residents of the ashram sit in a circle, their eyes fixed on Shyam, who has promised them a story as sweet as lemon syrup. And so Shyam begins.

While on some evenings he tells them of his boyhood days, surrounded by the abundant beauty of the Konkan, on others he recalls growing up poor, embarrassed by the state of his family’s affairs. But at the heart of each story is his Aai-her words and lessons. He reminisces of the day his mother showed him the importance of honesty and the time she went hungry just so her children could eat a full meal.

Narrated over the course of forty-two nights, Shyamchi Aai is a poignant story of Shyam and Aai, a mother with an unbreakable spirit. This evergreen classic, now translated by the incomparable Shanta Gokhale, is an account of a life of poverty, hard work, sacrifice and love.

When the World Went Dark

Jane De Suza

To help Swara, you’d have to dive into her world during the lockdown. Feel the almost-nine-year-old’s heart break as she loses her favourite person ever, Pitter Paati. Swara pursues clues to find her, but stumbles upon a crime instead. Vexpectedly, no one believes her.

Will Swara and her annoying friends from the detective squad find the Ruth of the Matter in time?

Told with humour and sparkle, this compassionate story is about finding light in the darkest times of our lives. It packs in an intriguing mystery and even a good belly laugh.

Karma Vs The Evil Twin

Evan Purcell

Everyone in Jakar knows that Karma has always defended his village from monsters. But suddenly his friends and neighbours are angry with him and accusing him of crimes he knows he didn’t commit.

Karma suspects he has a doppelgänger who is terrorizing the town, but no one believes him. His friends Chimmi and Dawa and even his mother do not seem to trust him.

But with every monster in Bhutan suddenly turning up in Jakar, will he be able to stop his adversary in time?

The third book in the Karma Tandin, Monster Hunter series, set in Bhutan, is a rollicking adventure that will keep you riveted till the very end!

Sometimes Mama, Sometimes Papa

Nandini Nayar

When Keya’s parents stopped living together, unusual things happened.

Keya became the only girl in her class with two homes.

‘Where will you live?’

‘Who will you live with?’

‘Sometimes Mama,’ Keya said, ‘sometimes Papa!’

This heart-warming story with comforting pictures reassures young readers that parents, whether alone or together, are always there for them.

How We Know What We Know

Shruthi Rao

There are millions of facts that we know about the world around us – that the earth is round, that birds migrate and that dinosaurs once roamed the planet. But how do we know what we know? Regaling us with tales of remarkable men and women who didn’t rest until they got the answers they sought, Shruthi Rao chronicles the stories behind the discoveries and inventions we take for granted today. This book, in fifty marvellous accounts, tells us of the sense of mystery and wonder that propel scientists to go after solutions to the puzzling problems of the world around us.