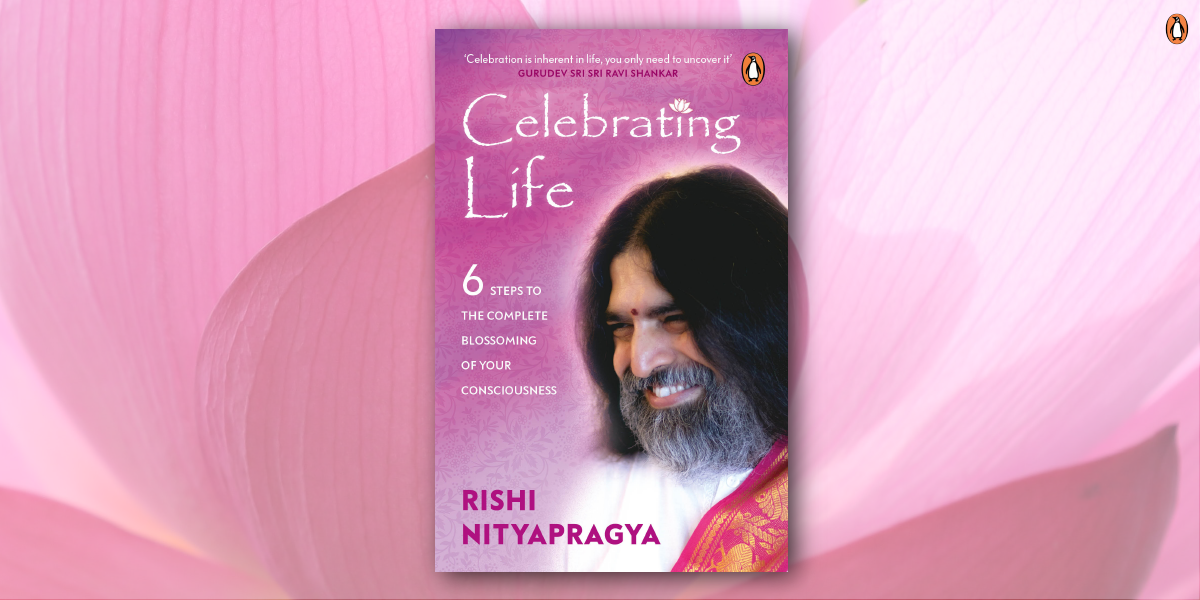

The universe has bestowed limitless powers and infinite siddhis on the human consciousness. Along with being effective and successful in the personal and professional spheres, the purpose of human life is also to ensure the complete blossoming of the individual consciousness. In Celebrating Life, Rishi Nityapragya shares the secrets that can help you explore your infinite potential. He offers an in-depth understanding of how to identify and be free from negative emotions and harmful tendencies, and how to learn to invoke life’s beautiful flavours-like enthusiasm, love, compassion and truth-whenever and wherever you want.

Here’s an excerpt from this profound book about overcoming the negative tendencies of the mind.

**

On the basis of past events, many people have the habit of blaming themselves. Small mistakes they have committed in the past lead them to form strong judgements about themselves, resulting in a sense of guilt, regret and self-blame. The exact opposite of that happens when some people develop the self-pitying tendency of blaming others for their miseries. They believe strongly that people are doing things to deliberately hurt them. This is called the victim consciousness, self-pity, the ‘poor-me’ attitude. The ego that makes you blame yourself is guilt complex. The ego that makes you blame others is victim complex. Both these flavours of the ego are extremely harmful—they are impediments to the blossoming of your life. Realizing your mistake is good enough; you don’t need to keep blaming yourself. Turn that pinch into a sense of commitment and resolve not to indulge in the same mistake again. Guilt is a wasted feeling. In the realm of consciousness, if you want to be free from any harmful habit, from negative tendency, from klisht vrutti, you need inner resilience and a sense of commitment connected with intense shakti (power), almost like a space rocket breaking the shackles of gravity by acquiring escape velocity and plunging into outer space. The guilt makes you feel bad about yourself, drains your energy, breaks the strength of your resilience and commitment.

People keep falling into this vicious cycle: they make mistakes, indulge in negative tendencies, feel guilty about them and blame themselves, but in a little while commit the same mistakes again. In order to attain freedom from negative tendencies, what you need is a strong, unwavering commitment, maintained for a substantial amount of time.

Guilt plays a counteracting role in this process. It destroys the strength of your commitment, which is necessary for you to break free of harmful tendencies.

The game of the victim ego is exactly the opposite of this. But before we go there, I want to remind you to be non-defensive and urge you to courageously look at the truth of life. Nature, existence, the universe, the Divine has given us so much. Let us take an example of this lifetime alone. From the time you took birth till today, in the so many years that you have passed in this physical body, look at how many wonderful things have happened to you. How much abundance has been bestowed upon each one of us! From getting the beautiful tool of this physical body, through which we are experiencing this wonderful life, to our family members who trigger so much love and a sense of support and security in us. Look at the variety of colours, flowers, fruits, vegetables, grains and spices nature has given us, for us to enjoy them all. Look at how the sun, the moon, the seasons, the seas, the wind and the rain have played their magnanimous roles in making your life so rich. In the ups and downs of this rollercoaster ride called life, look how the unseen hand of the Divine has always protected us. In the most challenging situations too, through different sources and in the form of different people, help has always come for you. But this extremely dangerous flavour of the ego, the victim consciousness, the sympathy-seeking, self- pitying, poor-me attitude, does not allow you to celebrate, appreciate or even acknowledge all these gifts of life. It tends o magnify your losses. When extraordinary benefits come your way, your victim ego never asks, ‘Why me?’ But as soon as something goes wrong, this poor-me runt starts cribbing and makes your life miserable.

In comparison with the positives of life, the negatives are minuscule, but the victim ego focuses on the negatives and puts on the glasses of self-pity and blame, through which this beautiful world begins to appear ugly, manipulative, almost demonic. People act according to their own tendencies, preferences, likes and dislikes, but when the victim ego colours your vision, viparyay takes over. Random, unintentional, insignificant gestures by people around appear to you as intentional and manipulative. These two flavours of the ego, guilt and victim complexes, have one thing in common: they thrive on blaming. This tendency to blame takes away your ability to respond to what is happening now. It does not allow you the freedom to drop the negativities and be free. It takes away your openness to celebrate life. In the process of blaming others, one completely disregards this basic, fundamental principle of life: ‘To keep your mind happy, pleasant and positive is your own responsibility.’

**