We recently spoke to Pankaj Bhadouria, the winner of MasterChef India Season 1. Pankaj has written two more cookery books, Barbie: I am a Chef and Chicken from My Kitchen.

Below are a few questions we asked her:

What was the very first dish that you cooked and for whom?

From what I remember, the first was probably breakfast for my Dad. The dish was nothing but toast, butter and tea with a rose on the tray. I must have been eight or nine years old at that time so the memory is very precious to me.

What is the best cooking related memory you have?

I think my best cooking related memory is when I was cooking for the finale at MasterChef. I was very calm and not under any pressure at all! I think that not only prevented me from making any mistakes but also reflected in the food that I created that day and helped me win.

Tell us the go-to spice mix in your kitchen.

That would be the Kadhai Masala! Be it with potatoes, chicken, paneer, cauliflower, stuffed paranthas – I use it almost everywhere!

Share with us a secret that you think helped you become the first MasterChef of India.

It is difficult to say…maybe a lot of homework that I’d done over the years aided by the fact that I could work well within limited time or perseverance and not giving up under pressure. Also I would pay a lot of attention to what comments my competitors would get from the judges and made it a point to not repeat those mistakes myself.

Are there more books coming from your kitchen?

Of course, there are! Just wait for what is next to come!

Tag: author interview

In Conversation with Faiqa Mansab

We recently spoke to the author of This House of Clay and Water, Faiqa Mansab. Her debut novel is set in Lahore and explores the themes of love, friendship and orthodoxy.

Below is our conversation with Faiqa, who is currently in Lahore:

Share your writing process behind The House of Clay & Water, how did you think of writing about the insidious power of orthodoxy in Pakistan?

I’ve come to believe that we write the stories that we are meant to; stories which only we can write. I come from a pluralistic and hybrid literary family tree. Punjabi Sufi poetry was always playing in the background at home. I grew up reading English literature, then graduated to American and European literatures, and all the while I was also reading Ghalib, Faiz, Mir, short story writers, novelists, women who wrote about the devastating Pakistan I lived in, yet I was so far removed away from it. Despite such a diverse education, I was never confused about my identity or my languages. I loved all three that were at my disposal and yearned for Persian and French.

I read whatever I could, except for comics. I’m afraid I’ve never appreciated comics. I read literary novels and also cross-genre novels like Du Maurier, Mary Stewart, Pat Conroy, Colleen McCollough and others who wrote beautifully but were still not considered ‘highbrow’. I wanted to write like all of them. I don’t think a writer makes a conscious decision to write about a topic or social issue.

This House of Clay and Water grew out of the first draft of another book that I had been writing prior to the MFA. It employed Magical Realism, sported a jinn, and a great deal of philosophy. After 60k words the story was still emerging and wasn’t very clear. It was called lyrical, beautiful and all that by my first readers, my class fellows, but I knew I had to let it go. I started the novel again, rooted in what is called ‘realism’ in literary terms. The female protagonist of the previous novel had stayed with me and moved premises into the new novel. She became stronger, her voice was so clear.

I’m very proud of my legacy, very rooted in this land, and my heritage. My writing stems from a place of deep love for this land, its customs and privileges, its tragedy and its sorrows. My memory goes back a long way; long before I was born, or my parents were born and this novel isn’t about orthodoxy waging wars on Pakistani turf, but orthodoxy waging war on spiritualism, on Sufism, on tolerance. It is hurtful. It is wrong. It isn’t us.

How did you come up with the different characters in your book, have you met such people in real life?

I never really know how to answer that question. If you mean, are they based on real people? Then no, they are not. If you mean that you will never see them in real life, then I’ve failed as a writer. They aren’t real but they had better be realistic. They are I think, or the biggest publishing house in the world wouldn’t have backed this book. (I love reminding everyone that Penguin has published my book).

Difference fascinates me. Peripheries and centers fascinate me. Power dynamics between genders and how social constructs mold people and their behaviors is frighteningly like living in a prison, like being conditioned and brain washed. When you really come down to it, we are all conditioned to behave in certain ways under given circumstances…like Pavlov’s dogs. There is very little agency in an average human life until and unless we actively go against the grain, at the risk of being ostracized, called mad or just hated.

I wanted to write about such people. Women who go against the grain are worse off than men even. They are intolerable. They are monsters that have to be killed to re-establish social order like in Sophoclean tragedy or Shakespearean tragedy, where the social sickness had to be rooted out, killed to purge the city state and bring peace. These aberrations are not tolerated.

Which brought me to those human beings the world considers aberrations, and ridicules, and humiliates: eunuchs, hermaphrodites, castrati’s. They were not treated this badly in the sub-continent until the British came along. The attitude of hate and humiliation towards hermaphrodites is a legacy of the British. In the traditional and historical culture of the sub-continent, hermaphrodites were treated with courtesy, even if they were not considered equal. But now we must do better for women and for transgenders.

Do you have any writing rituals?

Coffee. Nothing fancy, but hot, and at least two large mugs to start me off. I have a lovely little study, with a lilac ceiling, and a thick carpet of the same color and a small white mantle with my books on it. A writing table facing the wall which has my vision board from end to end, full of Van Gogh and Monet postcards, inspirational quotes and rules of writing from famous authors. I sit and I stare, drink my coffee and feel small and miserable. Then I drink another cup, and I feel better, less small, less insignificant, more ambitious. A few more sips, and I open my laptop. Its sleek and new, and has only my manuscripts. I begin by reading what I had written yesterday or day before. Sometimes I don’t see any mistakes and I’ll start typing happily. If I find mistakes, well, I start fixing them until I am tired. Then I get a new cup of coffee and start writing something new.

This happens only on good days. Sometimes coffee doesn’t work on feelings of smallness and insignificance. Those days I sit on my lilac armchair and read Proust. You know, one might as well go down in style.

How does the place affect your writing, in terms of setting as well as inspiration?

Place is important. Location is political. Location is the heart of the story. Sometimes it is the only story. For me that place is often Lahore. I will never understand this city. I’ve accepted that and that’s’ why I can write about it. It so complex and so Protean. I love writing about this city.

Any advice for aspiring writers?

Learn to edit your own work. Read it again and again till you’re sick of it and can see beyond your love for it and into the mechanics of sentences and paragraphs. Then get rid of everything extraneous.

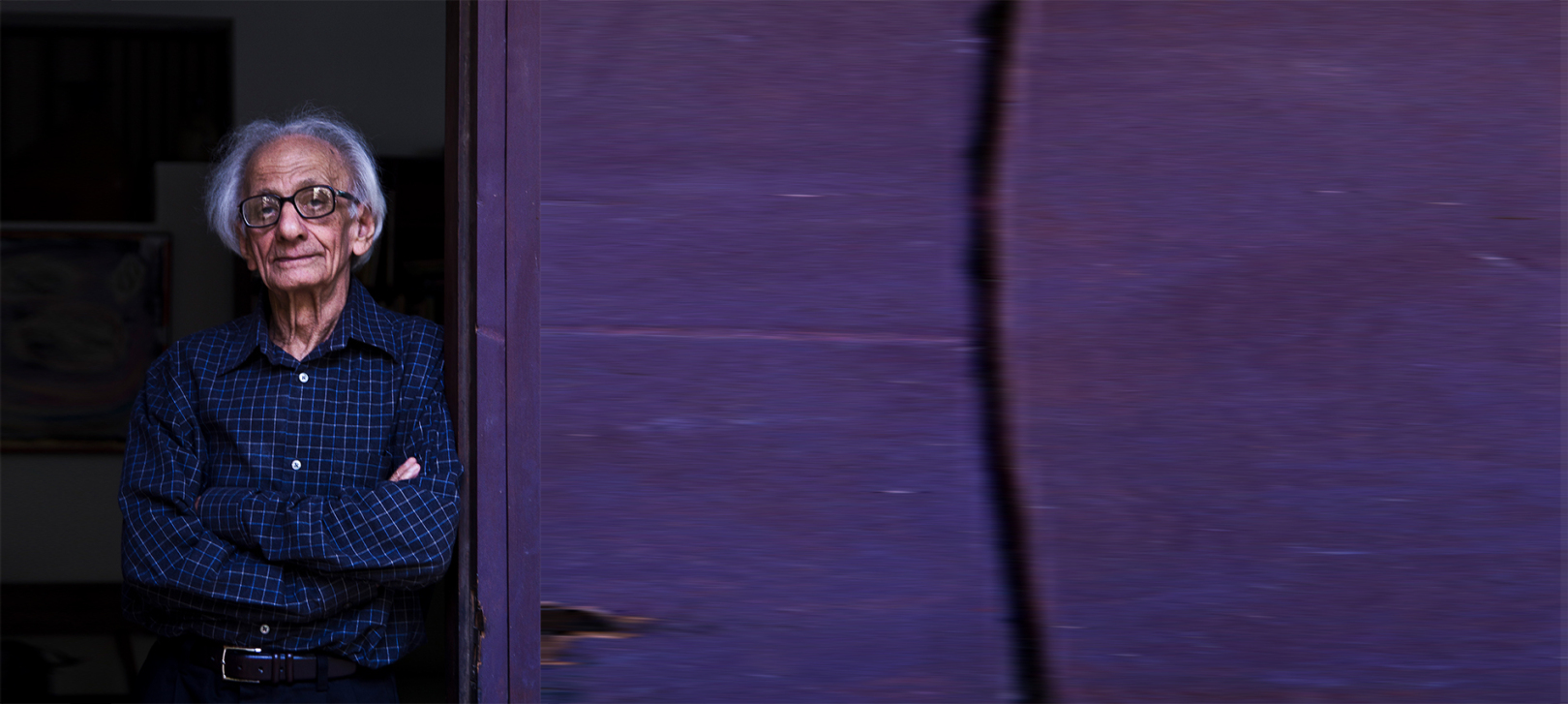

In Conversation with Krishna Baldev Vaid

We recently spoke to the author of None Other, the august 89-year old Krishna Baldev Vaid. He is well known for his books The Broken Mirror, Steps in Darkness and many more.

Below are a few questions we asked Vaid to know more about his writing process.

When you get an idea for a book, how does it form into a story? Please share your writing process with us.

It differs in details from piece to piece, from novel to novel, from play to play but essentially, it assumes the urgency and intensity of an obsession that elevates me to a level of receptivity, that is extraordinary if not abnormal, to intuitions, perceptions, choices of words and phrases and puns and euphonious effects, in short a style suitable to the occasion. The emphasis is never on story as such. My stories, both short and long, are never mere stories; my novels and plays do not aim at telling intricate and interesting and eventful stories. They do not require a well-designed plot. They create an atmosphere, an alternative reality, if you will, a universe of words and sounds and suggestions and characters that are both familiar and strange, normal as well as abnormal, mundane and magical, real and unreal, just as in dreams and nightmares.

Do you have any writing rituals that you follow?

I am afraid I do not have any writing rituals except perhaps a room of my own, a closed door, a wall in front of me, a space to pace up and down, silence, sometimes low and slow classical instrumental, preferably sarod, music. I tend to make fun of writing rituals in my novels and stories such as ”Bimal Urf Jayein To Jayein Kahan” (”Bimal in Bog” in English) and ”Doosra Na Koi” (”None Other” in English).

When I was young, I had a somewhat romantic association with writing and artistic rituals. In old age, every elderly movement and gesture and activity automatically and inevitably becomes ritualistic. You don’t need any other rituals.

How do you pick books that you want to translate? Is there a reason behind that choice, such as for Alice in Wonderland?

I am not a professional and a prolific translator into English or Hindi. I think I have translated more of my own stuff in Hindi into English than other writers’—alive or dead. I tend to believe I would have been less of a self-translator into English if there had been an active band of good professional translators into English from Hindi. Perhaps, in that case, I would still have used my bilingualism for doing some selective translations of some modernistic Hindi fiction and poetry as love’s labour or out of a sense of duty; I don’t know.

Two of my dear friends, Nirmal Verma and Srikant Varma, asked me to translate two of their novels, ”Ve Din” (Nirmal) and ”Doosri Baar” (Srikant), and I complied because I liked their work, but I did not ‘pick’ them. In the case of ”Alice in Wonderland”, I chose it for translation into Hindi because of its status as a classic, not only as a children’s book but for ‘children’ of all ages and, I believe, nationalities. I used to read it to my three little girls as they were growing up. Besides, the only great version available in Hindi was a great adaptation by a great Hindi poet, Shamsher Bahadur Singh—”Alice Ascharya Lok Mein.” I wanted to do a translation of the complete original text. The third major translation of an important book-long Hindi poem that I did was ”Andhere Mein” (”In The Dark”) by Muktibodh. I selected it because of my admiration for it as a modern classic by a great Hindi poet who died in splendid neglect except as a cult poet for the discerning younger Hindi poets, without a published collection of his own poetry.

I chose two plays of Samuel Beckett—”Waiting for Godot” and ”Endgame”—in 1968, before he became a noble laureate, because Beckett was my favourite modern writer. I wrote to him for permission while I was a visiting professor in English at Brandeis university. He wrote back a brief but gracious post-card from Paris after a couple of months, granting me permission even though he assumed I’d do my translation from his own English version of those plays written originally by him in French. I wrote back thanking him and mentioning that his assumption was correct even though I assured him that even though my French was inadequate, I’d also take into account his French original of the plays.

In addition to these three Hindi books, I also translated some Hindi poems and stories of some important Hindi writers, only one of whom—Ashok Vajpeyi—is alive: Shamsher Bahadur Singh, Srikant Varma, Muktibodh, Upendranath Ashk, Hari Shankar Parsai, Ashok Vajpeyi. All these have been published in English magazines but not collected in a book.

The only other notable translation into Hindi that I have done was commissioned by the French embassy in Delhi—it was Racine’s ”Phaedra”. I told them my Hindi translation would be from a standard English version of the original French and that I’d consult the original French with the help of my inadequate French. My Hindi version was published by Rajkamal Prakashan and was staged in Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal, and Delhi under the direction of an important and renowned French director, M. Lavadaunt.

How do you decide which language to write in and which one to translate into? And why?

This decision was made by me rather early in my life during my final year of M.A. in English at Govt. College, Lahore when I was only nineteen years old and living under the menacing shadow of the partitioned independence of India into two countries, India and Pakistan. My heart was set on being a creative writer, a fictionist. I already knew that I would have to do something else for earning a living if I wanted to write on my own terms without making any compromise with anybody. I did not want to write in English, even though I was fairly good in it and knew that I’d get better, because I didn’t consider it as an Indian language and did not dream in it. I didn’t want to choose Punjabi as my medium of creative expression, even though it was my mother tongue, because I didn’t consider it rich enough. The choice was between Urdu, which I was also good at thanks to my proficiency in Persian, and Hindi which I had almost entirely taught myself thanks to the similarity of its and Urdu’s grammar and syntax. With more of Hindi reading and the help of a good dictionary and with an openness to Urdu and Persian for the enrichment of my vocabulary, I could forge a style of my own that might even be better than standard stultified Hindi, or Urdu for that matter. I soon was able to achieve a style of my own free from the stiffness of both standard Hindi and Urdu and also the simplistic hotch-potch of the so-called Hindustani.

English is the only language I can translate my own Hindi books into; my own kind of Hindi is the only language that I can translate any English book into. Since I translate only what I like and want to and since I do not do it for my living, I do not do much translation. And now I am approaching the end and the final goodbye to all this.

Does the translation process differ when you are translating a book by an author other than yourself?

Yes, it does. If the other author is alive, you can refer your questions and problems and enigmas to him/her if he/she is easily accessible. If the author is dead or distant, metaphorically or really, you may either use your own discretion or consult an expert in that language or on that author.

If it is your own stuff that you are rendering into another language that you know well, you have only to refer to yourself for all questions and problems and enigmas and uncertainties. So in one sense you are free and self-sufficient but in another sense you are as lonely as you were when you were writing your original book. Of course, if in the course of self-translating if a new flash comes to you, you may as well take advantage of it without any compunction. You may end up adding to and subtracting from your original book. This addition and subtraction may help or harm the book but you are greater liberty in this case. Some writer friends of mine feel absolutely free to change their original books while translating them. Qurratullain Haider, an Urdu writer-friend who is no more was one such novelist of great merit. I did not read her own free self-translations into English but I did read several of her Urdu novels and was aleays charmed and impressed.

In my own case, when I was doing my own novel, ”Bimal Urf Jaayein To Jaayein Kahan”, into ”Bimal in Bog” for my friend P. Lal’s publishing outfit, Writers Workshop, I gave myself the freedom to welcome new ideas and flashes and linguistic arrangements and puns, etc., so that I had no objection when he changed ‘Translated by the author’ to ‘Transcreated by the author’. Even otherwise it seems to me now that all good translations are, to varying degrees, transcreations.

Are the themes of your writings related to your life experiences?

Perhaps, what you really meant to ask was: Are your novels and stories and plays autobiographical? But let me first answer your question as you phrased or framed it. The themes of one’s writings are always related to one’s life experiences. Even one’s entirely imagined themes are related in some way or other to one’s life experiences because one’s imagination is also shaped and determined by one’s own life experiences. Besides, all human experiences have an element of underlying universality that is a unifying factor which overrides apparent diversity. At the same time, every autobiographical detail undergoes an alchemical transformation in art. The tree or the flower you see with your eyes in real life is never the same as the one you describe or paint or sculpt or sing in your novel or paint in your picture or sculpt in your sculpture or sing in your music. The same is true of any feeling or emotion or action or happening, come to think of it. Even the most autobiographical detail undergoes a change through the alchemy of imaginative and creative writing.