If I cannot do great things, I can do small things in a great way.- Dr Martin Luther King, Jr

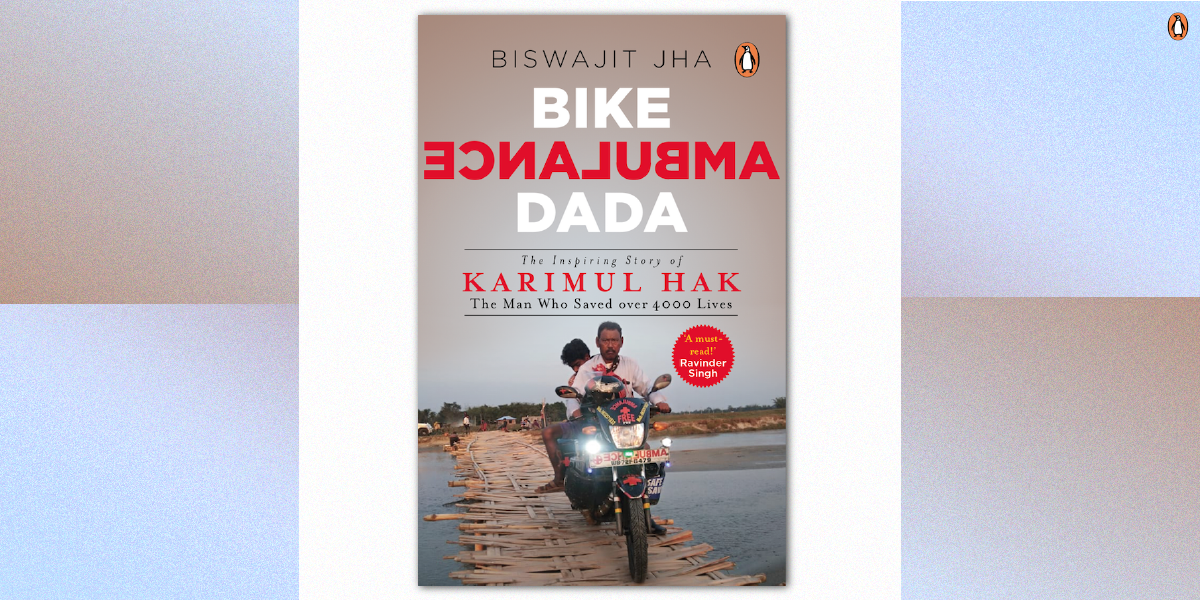

Bike Ambulance Dada, the authorised biography of Padma Shri awardee Karimul Hak, is the most inspiring and heart-warming biography you will read this year. It documents the extraordinary journey of a tea-garden worker who saved thousands of lives by starting a free bike-ambulance service from his village to the nearest hospital.

Here is an excerpt from Bike Ambulance Dada by Biswajit Jha titled A Bike Ambulance Takes Shape.

Now that Karimul had a bike, he was no longer dependent on his cycle to ferry a patient. The bike gave the patients a greater chance of survival by ensuring they got to the hospital quickly. Karimul, too, was under less pressure, physically and mentally; he could be more certain of patients getting timely medical attention, be they sick or injured, and riding a motorbike was far less physically taxing than cycling all the way with a passenger.

One day, in 2008, when Karimul was enjoying a cup of tea with some acquaintances at a tea shop in Kranti Bazaar, one of them, Babu Mohanta, suddenly cried out. The engrossing discussion on political affairs was halted abruptly. The small group sprang into action to find out the reason behind Mohanta’s shriek. Investigations revealed that a snake had bitten him just above the ankle. Karimul immediately made up his mind to identify the snake, as this would help the doctor decide on the course of treatment; it was imperative in such cases. He saw the snake but could not identify it. Thinking fast, he somehow caught the snake and put it in a small box so that he could carry it to the hospital. He applied a pressure bandage on the wound as well. With the help of those around them, Karimul got Mohanta tied to his back and asked a villager to ride pillion with him. Before starting out for Jalpaiguri Sadar Hospital, Karimul instructed the man to make sure that Mohanta did not fall sleep. The snake, carefully locked in the box, accompanied them to the hospital.

On the way, they met with a huge traffic jam on the bridge over the Teesta, just 5 kilometres from the hospital. The road was chock-a-block with vehicles stranded on the bridge, all trying to find a way out and, in the process, aggravating the situation. As Karimul zipped past the four- wheeled vehicles, he saw an ambulance stuck in the traffic. When he asked the ambulance driver for the patient’s details, he was told that the man had also been bitten by a snake, and they were heading for the same hospital as Karimul. Manoeuvring his much-smaller vehicle between the cars and moving towards the hospital with Mohanta, the soft-hearted Karimul felt sorry for the patient in the ‘proper’ ambulance, unable to get out.

Karimul soon reached the hospital. Once there, he showed the snake to the doctor, who was at first startled but then observed it intently for a few seconds before springing into action with the treatment.

After getting Mohanta admitted, Karimul went back to the bridge where they had seen the ambulance. He saw that the ambulance, along with other vehicles, was still there; the patient had, unfortunately, passed away.

After a couple of days, Babu Mohanta was released from the hospital. He was the first person bitten by a poisonous snake in the village to be saved—all because of Karimul’s timely intervention and bike ambulance service.

Before this incident, though Karimul had ignored the taunts of some of the villagers and had gone about ferrying patients to hospital, he had sometimes harboured misgivings that his bike ambulance was a poor substitute for the conventional ambulance. But that day, he realized that his bike ambulance was sometimes far more convenient than a standard ambulance. From then on, there was no looking back for him. His new-found confidence enthused him to serve people with increased passion.

After he was awarded the Padma Shri, the Navayuvak Brindal Club, Siliguri, donated to him an ambulance that he used for some months. But the traditional ambulance not only consumed more fuel, it was also rather difficult to drive it to remote and far-flung areas. After some weeks, he stopped using that ambulance; though it is still with him, he doesn’t use it. Instead, he now has three bike ambulances at home; one is used by his elder son, Raju, another by his younger son, Rajesh, while Karimul himself mostly uses the bike ambulance donated by Bajaj Auto, which has an attached carrier for patients.

Thanks to Karimul Hak’s unique initiative, the bike ambulance has become popular in rural areas of India. Inspired by him, some social workers, as well as some NGOs, have started this service too, thereby saving thousands of lives in far-off areas of the country.

While Karimul has saved many lives, he deeply regrets not being able to save some. Still, he derives immense satisfaction from the fact that a person like him, with a paltry income and limited capacity, has made a difference in the lives of so many people. Relatives and family members of those who died en route to the hospital, or even after reaching the hospital, at least know that they, through Karimul, tried their best to save their loved one. This is a noteworthy achievement for Karimul, who dreams of a day when lack of medical treatment will not be the reason for someone’s death.

Bike Ambulance Dada is a must-read today as it will inspire us to do and be better in our lives.