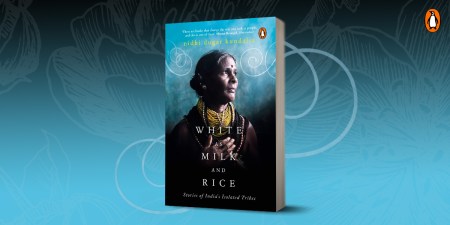

The Maria girls from Bastar practise sex as an institution before marriage, but with rules-one may not sleep with a partner more than three times; the Hallaki women from the Konkan coast sing throughout the day-in forests, fields, the market and at protests; the Kanjars have plundered, looted and killed generation after generation, and will show you how to roast a lizard when hungry.

Lying on the mattress, Mani follows the movement of his father’s breathing. Moments ago, he had watched his father’s sweaty hips thrust up and down while his stepmother, Bindu, lay still beneath him, muffling her pain. His father stayed silent, though maybe his lips kept moving – he was always moving his lips as though he were talking to someone invisible. A mongrel laid beside Mani’s feet, its ears pricked for the sound. Each time his stepmother moaned, the dog yelped.

Like most other children in Hulikkal, a small village in the Nilgiris, Mani lives in one-room mud hut, where pots and pans are pushed aside every night to make room for mats, where they can hear their parents make love, or whatever else it is, through the mosquito net that hangs between them. He shifts on the floor; his upper back hurts from being slammed against walls by his angry father when he had come back jobless from the Badaga village.

“I can’t pay for the giant morsels you eat any more,” he had shouted as he thrashed Mani. Mani wonders what it must be like growing up in the big Badaga houses he saw today, where children sleep in different rooms, thick brick and cement walls separating them from their parents.

He had not seen anything quite like the homes that appeared in the Badaga village: concrete square structures with windows painted smooth in purple, green and blue, with large vegetable patches or a stretch of tea estate sloping down in front. Each home had a little chimney with smoke swirling from it like the incense sticks his father used for the pujas.

The trees and bushes were all trimmed; from the top of the hills, he could see fields of tea, with men and women moving through them, carrying their baskets on their backs, their feet stained red from the soil. When it rains in the Nilgiris, this red earth trickles like blood under its green skin.

Earlier in the day, Mani and his uncle had walked uphill after getting off the bus; the long walk had made his legs hurt, but that did not bother him. He was willing to cross many more such hills. In the absence of trees, that part of the Nilgiris was full of gusty wind that stung his eyes till tears stained his cheeks.

When his uncle spoke, the winds carried his voice louder than he meant it to be, “I told them you already know sowing”; he’d brought him here for a daily wage job at a tea garden. Mani nodded, although he’d hardly worked in fields: They had only a small plot where they grew vegetables and some millet.

On other days, they ate what they collected – roots of yam, herbs and honey – from the forest where they lived or rice given to them by the government. This village, meanwhile, only housed the Badagas, an educated, prosperous tribe that had migrated to the Nilgiris in the early twelfth century. The estate owner his uncle was taking him to had political aspirations and everything he did was to be transactional, driven by the desire to secure votes. Among his pet constituencies were the hamlets of the Kurumbas, also some of the poorest people in Nilgiris, and the area beyond.

“Call him appa,” his uncle insisted, in the Alu Kurumba language, a mix of Tamil and Kannada.

“Remember, you’re a Kurumba. Do not stare at their family members.” Mani nodded, though his uncle had already told him this many times, just as he had told him to pat his hair down and not to say inane things: They are all educated, so don’t talk any jungle hocus-pocus.

Mani wished people did not speak to him as if he were a jungle idiot; that said, he couldn’t help but gape at the women who were walking their children to school. How smooth their skin was, their hair shining with oil, decorated with jasmine and plaited neatly with ribbons; their eyes, unlike the yellowed eyes of Kurumbas, were as white as their teeth.

Minutes later, Mani waited outside the Badaga man’s house, while a few boys chatted on their way back from school, clapping each other’s backs, laughing as they walked past him. Only a few from his hamlet went to school, but he could read what was written on their bag – “Government”. He recognised the word from its shape – it was on every pamphlet and poster handed to them.

One of the boys said something that made the others shout with laughter. Mani bunched the hole in his shirt with his fist while admiring their uniforms. They then slowed their steps to look back at their friends coming behind them, signalling them to join. That was what he wanted to do when he got older – saunter with friends through these neat little hills, talk and laugh.

When Mani looked at them again, one of the them seemed to be pointing at him, at his hair matted like a mop on his head, teeming with vermin. After some whispering, one of the boys, pretending timidity, wrung his hands beseechingly before Mani, “Spare me, oh Kurumba! Spare me from your sorcery,” and ran up the lane with the others, received by them with a hoot of laughter and much back-slapping. Mani had squeezed his eyes shut against the fierce brightness in which the boy’s oiled head laughed and moved among the waves of sudden bright sunlight.

When he recovered his vision, Mani ran behind them, but only mustered enough courage to spit in their compound. Before the Badaga estate owner could see them, his uncle tugged at his wrist and hurried him back to the bus stop. The sun was sinking behind the mountains without any play of colours or movement, save for their flustered stomp downhill.

It was only in these last few years that his forest tribe, the Kurumbas, had started working in the fields of Badagas during the day. Until a few years ago, whenever the forest tribals came in view of a Badaga, word flashed through their village, and women and children ran for the safety of home, hiding inside till the Kurumbas had gone.

If Mani knew a spell or two, he would have twisted those boys’ knickers till they fell screaming from groin pain, and practise the sorcery that they claimed his people knew.

The Kurumbas, they said, had medicines that could put all the inhabitants of a Badaga village to sleep before slinking back into the woods. Their ace sorcerer, an odikara, could make openings in the fence, and the Badaga’s livestock, under his spell, would follow him through it without so much as a cluck or a bleat. They could, apparently, turn into bears and kill people, just as they knew how to counter the other spells, to remove or prevent misfortune.

Many decades ago, when the Badaga grandfathers were little boys still hanging from their mothers’ waists, one of their elders returned from a Kurumba settlement situated outside the jungles, where he went to scout a plot for tea planting. He came back breathless, just about stuttering that their end was near and that a monster was around. Now, a Badaga knew that if a Kurumba sorcerer was casting spells, he could be appeased with rice, oil, salt and clothes. But what was this big brown animal he was screaming about, its eyes glowing red?

As the story goes, the goats, hens and cows were restless; they knew for certain that the elderly man had seen an irate Kurumba-turned-monster. All night, they howled in their sheds and tapped the ground, and the villagers slept fitfully, imagining figures and shapes in the hilly darkness.

The Badaga elders today still fear the sorcerer Kurumbas, often banding against them; their school-going children, though, have less faith in the Kurumbas’s magical abilities. “Isn’t your father, what is his name…Moopan? The limping old man who pretends to be a doctor?” a boy had teased Mani at the bus stop.

The Kurumba magic was wearing off, and a pervasive sense of futility remained. There it was, a distant murmur telling Mani that this fat Badaga life was not his birthright; there was always the possibility of running into people who spoke in hushed whispers around him; always a chance that however clean a shirt he wore, a passer-by may assume from his yellow eyes and uncouth hair that he was not a farm owner but the son of Moopan, the limping old sorcerer. His uncle had fallen asleep on the bus ride back home; Mani’s eyes burnt as he looked out at the rolling tea estates of the Badagas.