In Thinking of Winter, Shantanu Naidu reflects on isolation, responsibility, and the small, life-altering choices we make in moments of despair. The following excerpt captures the quiet transformation that begins when Winter enters his life.

***

People do selfish things when they are lonely. I don’t know if that justifies it, but I did them too.

In the eighth month of university, all the love letters posted abroad were spent, all the attempts to make friends had failed, and all that there was to do at the end of every day at Cornell, was to look in the mirror in disbelief: This was not how I thought it would be.

I would like to believe that a lot of smaller breakdowns over a longer period of time lead to a single moment that brings you to your knees and makes you give up once and for all. It can be losing your keys, or a phone call that wasn’t picked up, or missing the last bus home.

But what did ‘giving up’ even mean? There was a library of answers to that question. I, however, chose the most selfish one.

His name, was Winter.

Let’s be abundantly clear. Bad dogs do not exist. This is a blanket rule. There are no bad dogs, and we could, of course, delve deeper into unpacking this and talk about bad parenting and other reasons for some dear souls come to have behaviours that make them seem like bad boys, but for now, we’re just going to establish the inexistence of bad dogs.

I am in favour and support of a very large community of human beings who greet every dog with ‘whoozagoodboy’’ and sure enough the answer is and always should be, hesagoodboy.

But not Winter, no. A few million times during this story I will remind you with sweet frustration that I simply do not know what it was: genetics, soul, character or maybe something beyond our limited understanding of the world. But I do not know what was wrong with Winter.

Winter was a golden retriever, a runtof-the-litter puppy in a far-off town called Moravia while I studied in Ithaca. Forsakenness had me ride there, claim him one night in the fall of 2016, and bring him home a month later with the only friend I had: a Taiwanese introvert called Wen-Ko.

In the first week of Winter in my student apartment, while I contemplated daily whether I was even remotely capable of taking care of another life, Winter was busy stuffing himself in every gap that could be defined as one, even the ones that barely qualified. The only way to find him was to spot an absolute bushy butt sticking out of one place or the other. Some days easy to spot, some days laying still, waiting to be discovered, or worse, rescued.

As the urine stains on the carpet began to stay as contemporary art forms, depending on how hard you squinted, me and Wen would sit amidst them, saying very little but with the shared activity of looking at whatever Winter was up to in the room. Which, of course, was identifying gaps and stuffing himself in them.

Wen, a germophobe, who likes every aspect of her life in complete order, would watch in silence as Winter would create another pee spot next to her. Wen, the germophobe, would say nothing. As one loner to another, she accepted, in not so many words or any words, the reason why Winter was there in the first place. Her being there with us a was a strong nod in my direction saying, ‘If this is what will rescue you, I will support it.’

The Barron’s dog bible on golden retrievers that I had picked up in Boston instead of attending a job interview had me brace myself for what was to come after pee spots: poop on the carpet, furniture chewing, destroyed shoes, destroyed cables, lots of biting—unruly, unhinged, drunk puppy behaviour—and I was very ready for the damage. My roommate, on the other hand, was unaware, let alone prepared.

But it never happened.

Shoes stayed intact and the furniture unbothered. Cables right where I left them. Not a bark or a whimper. Nor a bite or a scratch. And while I waited patiently, anticipatingly almost, for Winter’s standard puppy phase, he seemed to have missed the memo.

***

Get a copy of Thinking of Winter from Amazon or wherever books are sold.

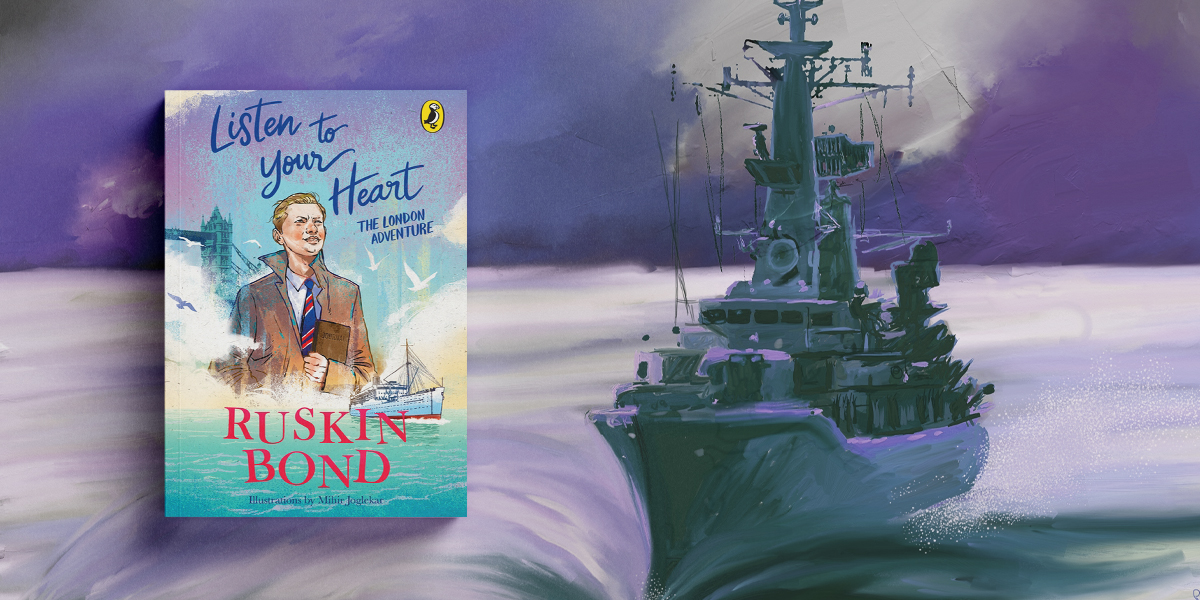

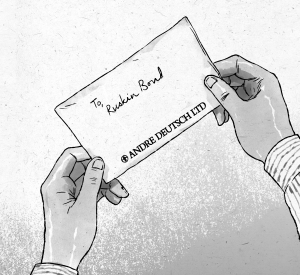

But along with the third or fourth flop of the returned manuscript came a letter from the editor at André Deutsch Ltd, a new publisher who was making a name and a reputation with some offbeat publications. The editor who wrote to me was called Diana Athill, and she wrote a very sympathetic letter, saying how much she liked the book and promising to reconsider it if I would consider turning it into a work of fiction, a full-fledged novel.

But along with the third or fourth flop of the returned manuscript came a letter from the editor at André Deutsch Ltd, a new publisher who was making a name and a reputation with some offbeat publications. The editor who wrote to me was called Diana Athill, and she wrote a very sympathetic letter, saying how much she liked the book and promising to reconsider it if I would consider turning it into a work of fiction, a full-fledged novel. were allies; they were a part of me, and they would be a part of my work. But it was to be a few months before I could launch out on my own, and during that time, I worked on the novel, pleased my employers and got on with my relatives as best as I could. My aunt never bothered me; in fact, she rather liked having me around. The youngest of my cousins was a friendly little chap; the other two rather resented me. Whenever I had the opportunity, I went to the cinema, and one of the films released at the time was Jean Renoir’s The River, based on the novel by Rumer Godden. This beautiful film made me so homesick that I went to see it several times, wallowing in the atmosphere of an India, a lot like the India l had known. The ‘river’, and its eternal flow became a part of my story too, especially the part where Kishen and Rusty cross the Ganga on the way back to their homes. And back in India, a young filmmaker called Satyajit Ray saw The River and realised that a film could also be a poem, and went about making his own cinematic poetry.

were allies; they were a part of me, and they would be a part of my work. But it was to be a few months before I could launch out on my own, and during that time, I worked on the novel, pleased my employers and got on with my relatives as best as I could. My aunt never bothered me; in fact, she rather liked having me around. The youngest of my cousins was a friendly little chap; the other two rather resented me. Whenever I had the opportunity, I went to the cinema, and one of the films released at the time was Jean Renoir’s The River, based on the novel by Rumer Godden. This beautiful film made me so homesick that I went to see it several times, wallowing in the atmosphere of an India, a lot like the India l had known. The ‘river’, and its eternal flow became a part of my story too, especially the part where Kishen and Rusty cross the Ganga on the way back to their homes. And back in India, a young filmmaker called Satyajit Ray saw The River and realised that a film could also be a poem, and went about making his own cinematic poetry.