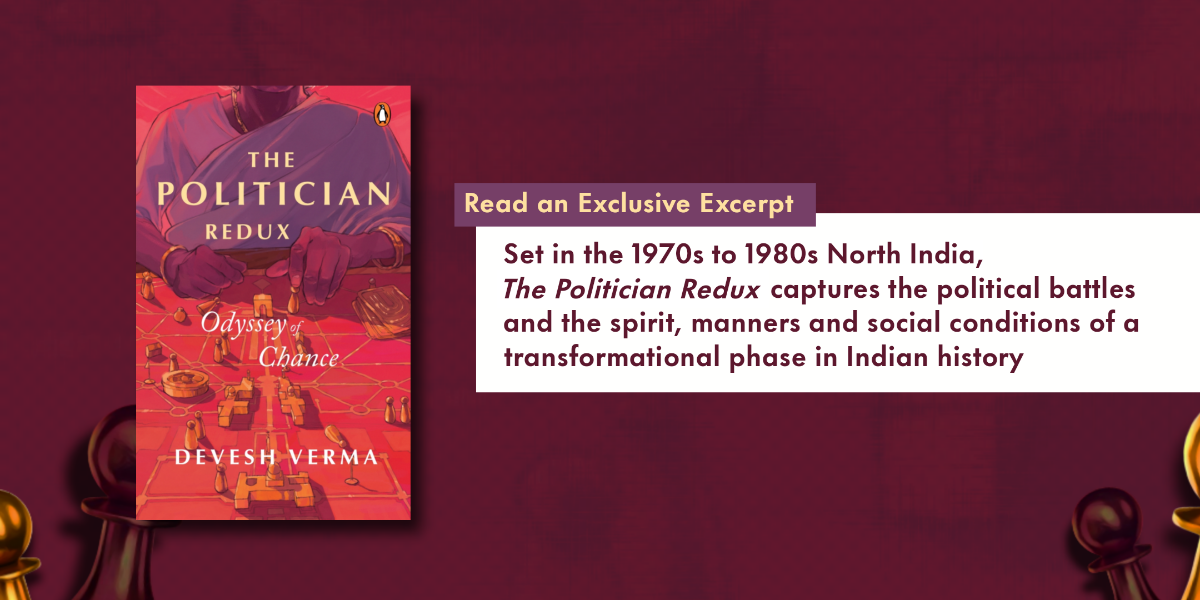

Ever wondered what politics looked like in India during the 1970s and 1980s? The Politician Redux by Devesh Verma has all the answers. Join Ram Mohan’s journey as he lands on the UP Public Service Commission, having been denied a cabinet position. Against the backdrop of the JP movement shaking up the Congress regime, Ram Mohan’s story unfolds amidst significant changes in Indian history.

Read this excerpt to experience the political intrigue, societal upheaval, and relentless pursuit of power in this thrilling sequel to The Politician.

***

There had been signs of popular unrest and political turmoil across an enormous chunk of India, and the way it came to grow in scope and intensity was staggering. Ram Mohan was thankful to Saansadji, the Chief Minister, for sending him to the Commission. Handpicked by Indira Gandhi, no Congress CM had the resources of his own to handle a crisis of this nature. It had all begun in the state of Gujarat, this flaring up of popular rage at inflation, where, incensed at their increased mess bill, students at an engineering college assaulted a college official, and put the canteen to the torch, following it up with another bout of destruction of college property. The trouble metastasized to other educational institutions Students were baying for the sacking of the state government led by one of the most corrupt Congress leaders, Chimanbhai Patel, who had procured massive funds for the party through questionable means. That inflamed the situation on the price rise front. Then, Jayprakash Narayan, an esteemed socialist figure, decided to lend his support to the agitation in Gujarat. Having been associated with the freedom struggle, he had once been invited by Nehru to join his cabinet. He had declined and quietly settled down in his home state, Bihar, emerging now and again from his retirement to pick up odd causes. Soon to be known as JP, he hailed the Gujarat students’ angst, seeing it as a force that could bring about the redemption of the country from corruption infesting the Indian polity.

With the students’ anger winning public endorsement, the situation in Gujarat became one of pandemonium. Violence and vandalism were rampant. The opposition latched on to the agitation, and Indira Gandhi had had to remove the Chief Minister placing the state under President’s rule while the opposition clamoured for the dissolution of the assembly and fresh polls. She was unwilling. Forcing her hand was a fast unto death to which her old foe Desai, the tallest leader of Gujarat, had resorted. Meanwhile, students in the lawless Bihar had put together their own movement with the opposition in tow, the grievances being the same as in Gujarat: corruption, price rise unemployment.

With rioting, arson vandalism becoming the order of the day, Bihar was thrown into anarchy. There was also this strike by railway workers when hundreds of thousands of them stopped work, demanding pay parity with other government employees. A little prior to this twenty-day-long, debilitating strike that had to be broken up by the government, JP had agreed to take up the reins of the Movement. Sensing general discontent, he resurrected his old idea of ‘total revolution’ and, with the opposition rooting for him, took the Movement beyond his home state, appealing to people, chiefly the youth, to rise against the misrule of Indira Gandhi. In the meantime, Saansad-ji’s reputation took a knock when the Congress lost a by-election for Allahabad, the parliamentary seat from which he had resigned to become member of the state legislature.

It was against this backdrop of growing bitterness of the Congress rule that Ram Mohan went to see Saansad-ji in Lucknow. He wanted to thank him for the Commission that had inaugurated a delightful chapter in his life ‘This was the best I could do in the circumstances and take my word, it’s one of the most coveted non-political positions. As Member Public Service Commission, you’ll have a term of sixyears during which nobody can touch you, whereas no political

office can be immune to instability.’ ‘Yes, I have a large family to provide for. I need stability. But whenever I’m needed in active politics, you’ll find me standing right behind you.’ Saansad-ji laughed. A listless laugh. His heart wasn’t in it.

You’d remember that within four months of my taking over as CM, Jayprakash ji came to UP to campaign for his total revolution. I didn’t try to stop him. I declared him our state’s guest, arguing that not only was he a renowned freedom fighter but a crusader for the good of the common man. This, I did, to restrain the rabble-rouser in him. Look at the response he’s getting wherever he goes! But Indira-ji listens to Shukla-ji’s wily Uncle Uma Kant Shukla and the like. These two things the way Congress was licked in Allahabad by-poll and the welcome extended to JP by my government didn’t go down well with her. There’s something else. She hasn’t taken kindly to my style of functioning . . . No Congress CM is supposed to govern in a manner that casts him as a leader under his own steam. Your only objective as minister or chief minister should be to keep the masses glued to the thought of her person,’ Saansad-ji paused to sip his tea. ‘JP is heading a movement out to undermine the Congress regime, and my action was nothing but a calculated move, a gambit. That’s what I tried to explain to her coterie. Some agreed. What I should worry about most, Ram Mohan, is the misgiving she might have about my motive. That’s why somebody advised me to avoid the trap of going after personal popularity.’

***

Get your copy of The Politician Redux by Devesh Verma wherever books are sold.