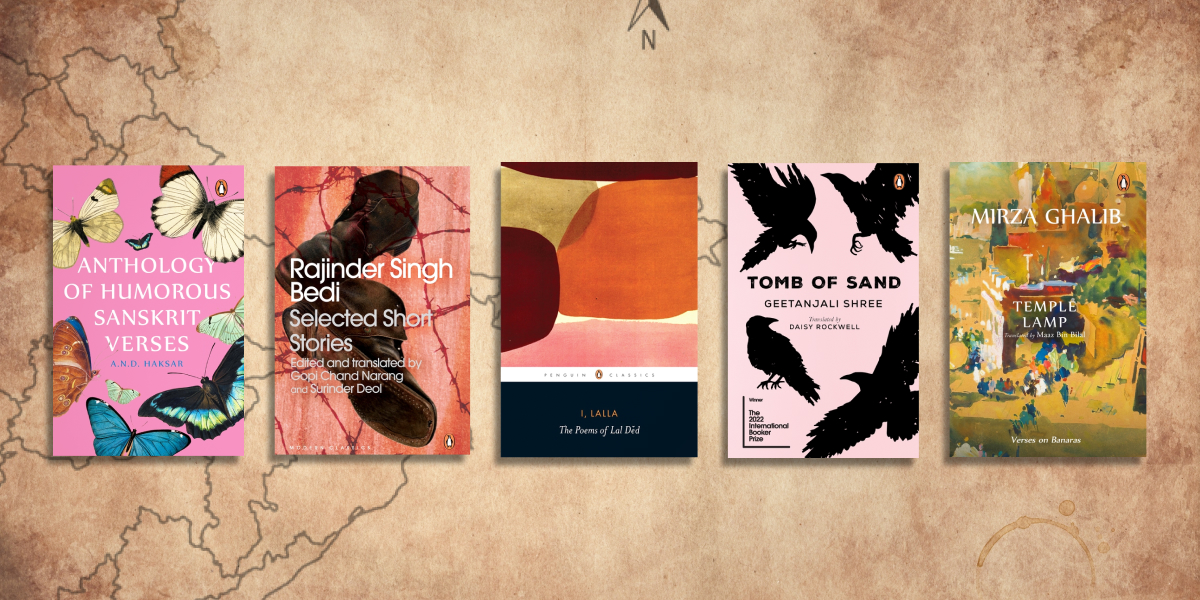

Here is our list of 16 must-read books in translation, from the length and breadth of the country.

As a reader, you are bound to be a little more inquisitive than the general population. So, your incredible brain must not be limited to the understanding of the diverse nation that we know India to be with the variety of languages, food, clothes and spices grown its separate regions. You must delve deeper! And nothing can tell you more about a land and its people than their stories. Let this specially-curated list act as your binoculars for taking a good look at India!

Tomb of Sand

WINNER OF THE INTERNATIONAL BOOKER PRIZE 2022

In northern India, an eighty-year-old woman slips into a deep depression after the death of her husband, and then resurfaces to gain a new lease on life. Her determination to fly in the face of convention – including striking up a friendship with a transgender person – confuses her bohemian daughter, who is used to thinking of herself as the more ‘modern’ of the two.

To her family’s consternation, Ma insists on travelling to Pakistan, simultaneously confronting the unresolved trauma of her teenage experiences of Partition, and re-evaluating what it means to be a mother, a daughter, a woman, a feminist.

I, Lalla

The poems of the fourteenth-century Kashmiri mystic Lal Ded, popularly known as Lalla, strike us like brief and blinding bursts of light. Emotionally rich yet philosophically precise, sumptuously enigmatic yet crisply structured, these poems are as sensuously evocative as they are charged with an ecstatic devotion. Stripping away a century of Victorian-inflected translations and paraphrases, and restoring the jagged, colloquial power of Lalla’s voice, in Ranjit Hoskote’s new translation these poems are glorious manifestos of illumination.

Anthology of Humorous Sanskrit Verses

In recent times, whenever ancient Sanskrit works are discussed or translated into English, the focus is usually on the lofty, religious and dramatic works. Due to the interest created by Western audiences, the Kama Sutra and love poetry has also been in the limelight. But, even though the Hasya Rasa or the humorous sentiment has always been an integral part of our ancient Sanskrit literature, it is little known today.

Anthology of Humorous Sanskrit Verses is a collection of about 200 verse translations drawn from various Sanskrit works or anthologies compiled more than 500 years ago. Several such anthologies are well-known although none of them focus exclusively on humor. A.N.D. Haksar’s translation of these verses is full of wit, earthy humor and cynical satire, and an excellent addition of the canon of Sanskrit literature.

Temple Lamp: Verses on Banaras by Mirza Asadullah Beg Khan

The poem ‘Chirag-e-Dair’ or Temple Lamp is an eloquent and vibrant Persian masnavi by Mirza Ghalib. While we quote liberally from his Urdu poetry, we know little of his writings in Persian, and while we read of his love for the city of Delhi, we discover in temple Lamp, his rapture over the spiritual and sensual city of Banaras.

Chiragh-e-dair is being translated directly from Persian into English in its entirety for the first time, with a critical Introduction by Maaz Bin Bilal. It is Mirza Ghalib’s pean to Kashi, which he calls Kaaba-e-Hindostan or the Mecca of India.

Selected Stories: Rajinder Singh Bedi

Rajinder Singh Bedi: Selected Short Stories curates some of the best work by the Urdu writer, whose contribution to Urdu fiction makes him a pivotal force within modern Indian literature. Born in Sialkot, Punjab, Rajinder Singh Bedi (1915-1984) lived many lives-as a student and postmaster in Lahore, a venerated screenwriter for popular Hindi films and a winner of both the Sahitya Akademi as well as the Filmfare awards. Considered one of the prominent progressive writers of modern Urdu fiction, Bedi was an architect of contemporary Urdu writing along with leading lights such as Munshi Premchand and Saadat Hasan Manto.

Battles of Our Own

Jagadish Mohanty’s Battles of Our Own is a rare work of modern Odia and Indian fiction. It seeks to delineate a world that is off the grid. Its action unfolds in the remote and non-descript Tarbahar Colliery-a fictional name for the over hundred-year-old open-cast Himgiri Rampur coal mine in the hinterland of western Odisha. A work of gritty realism in its portrayal of a dark and dangerous underworld where coal is extracted, the novel poignantly reveals the primeval struggle between man and brute nature.

Four Chapters

Char Adhyay (1934) was Rabindranath Tagore’s last novel, and perhaps the most controversial. Passion and politics intertwine in this narrative, set in the context of nationalist politics in pre-Independent India.

This new translation, intended for twenty-first-century readers, will bring Tagore’s text to life in a contemporary idiom, while evoking the flavour of the story’s historical setting.

Hungry Humans

Ganesan returns, after four decades, to the town of his childhood, filled with memories of love and loneliness, of youthful beauty and the ravages of age and misfortune, of the promise of talent and its slow destruction. Seeking treatment for leprosy, he must also come to terms with his past: his exploitation at the hands of older men, his growing consciousness of desire and his own sexual identity, his steady disavowal of Brahminical morality and his slowly degenerating body. He longs for liberation-sexual, social and spiritual-but finally finds peace only in self-acceptance.

Vultures

Based on the blood-curdling murder of a Dalit boy by Rajput landlords in Kodaram village in 1964, Vultures portrays a feudal society structured around caste-based relations and social segregation, in which Dalit lives and livelihoods are torn to pieces by upper-caste vultures. The deft use of dialect, graphic descriptions and translator Hemang Ashwinkumar’s lucid telling throw sharp focus on the fragmented world of a mofussil village in Gujarat, much of which remains unchanged even today.

Cobalt Blue

A paying guest seems like a win-win proposition to the Joshi family. He’s ready with the rent, he’s willing to lend a hand when he can and he’s happy to listen to Mrs Joshi on the imminent collapse of our culture.

But he’s also a man of mystery. He has no last name. He has no family, no friends, no history and no plans for the future.

The siblings Tanay and Anuja are smitten by him. He overturns their lives. And when he vanishes, he breaks their hearts.

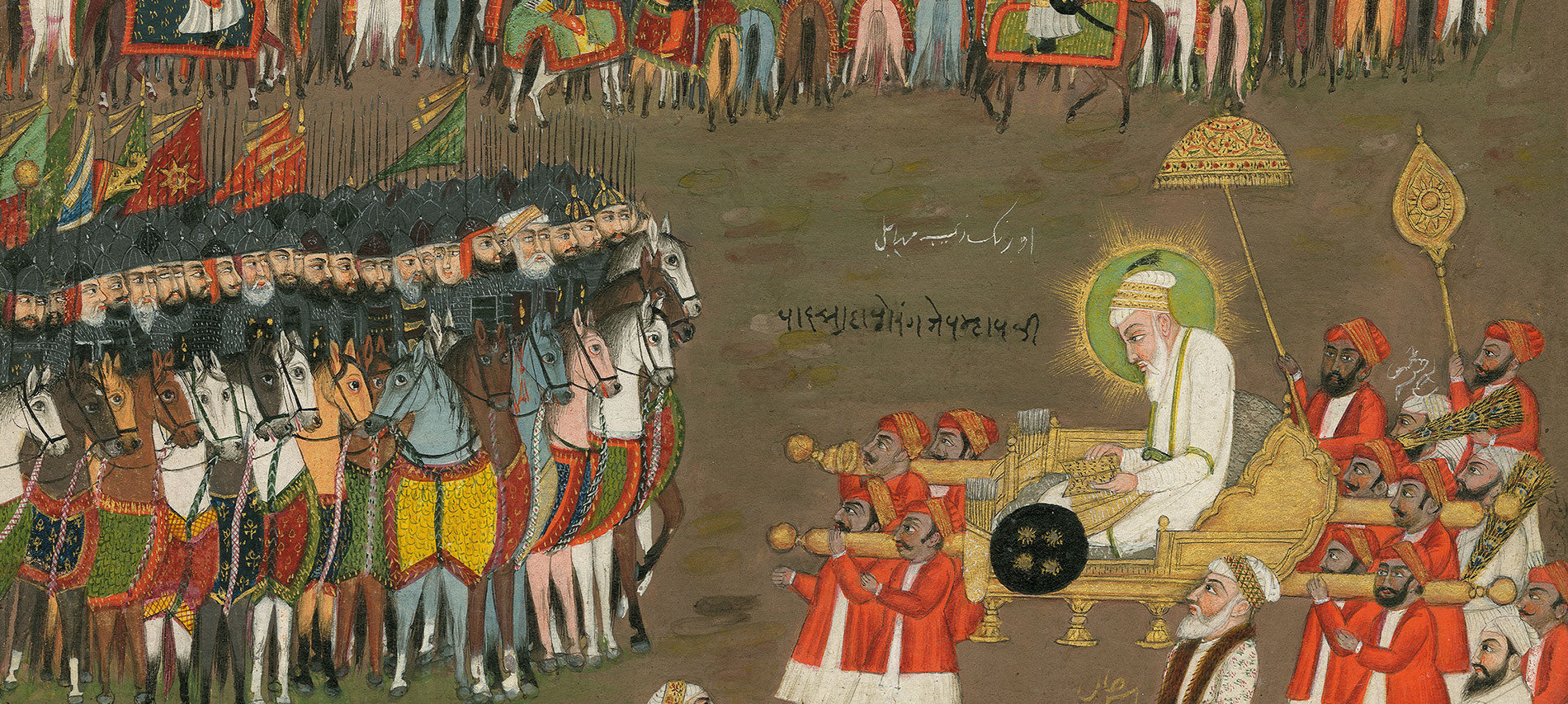

The Prince and the Political Agent

The Manipuri writer Binodini’s Sahitya Akademi Award-winning historical novel The Princess and the Political Agent tells the love story of her aunt Princess Sanatombi and Lt. Col. Henry P. Maxwell, the British representative in the subjugated Tibeto-Burman kingdom of Manipur. A poignant story of love and fealty, treachery and valour, it is set in the midst of the imperialist intrigues of the British Raj, the glory of kings, warring princes, clever queens and loyal retainers.

Hangwoman

The Grddha Mullick family takes pride in the ancient lineage they trace from four hundred years before Christ. They burst with marvelous tales of hangmen and hangings in which the Grddha Mullicks figure as eyewitnesses to the momentous events that have shaped the history of the subcontinent.

In the present day, the youngest member of the family, twenty-two-year-old Chetna, is appointed the first woman executioner in India, assistant and successor to her father Phanibhushan. Thrust suddenly into the public eye, even starring in her own reality show, Chetna’s life explodes under the harsh lights of television cameras. As the day of her first execution approaches, she breaks out of the shadow of a domineering father and the thrall of a brutally manipulative lover, and transforms into a charismatic performer in her own right.

Ha Ha Hu Hu: A Horse-Headed God in Trafalgar Square

Ha Ha Hu Hu tells the delightful tale of an extraordinary horse-headed creature that mysteriously appears in London one fine morning, causing considerable excitement and consternation among the city’s denizens. Dressed in silks and jewels, it has the head of a horse but the body of a human and speaks in an unknown tongue. What is it? And more importantly, why is it here?

In the hilarious satire Vishnu Sharma Learns English, a Telugu lecturer is visited in a dream by the medieval poet Tikanna and the ancient scholar Vishnu Sharma with an unusual request: they want him to teach them English!

Tejo Tungabhadra: Tributaries of Time

Tejo Tungabhadra tells the story of two rivers on different continents whose souls are bound together by history. The two stories converge in Goa with all the thunder and gush of meeting rivers. Set in the late 15th and early 16th century, this is a grand saga of love, ambition, greed, and a deep zest for life through the tossing waves of history.

Phoolsunghi

The first ever translation of a Bhojpuri novel into English, Phoolsunghi transports readers to a forgotten world filled with mujras and mehfils, court cases and counterfeit currency, and the crashing waves of the River Saryu.

Lilavati: A Life

In a moment of rare passion Govardhanram Madhavram Tripathi, author of Sarasvatichandra, exclaimed ‘I only want their souls’. He was referring to the souls of his countrymen and women, which he sought to cultivate through his literary writings. Lilavati was his and Lalitagauri’s eldest daughter. Her education and the writing of Sarasvaticandra were intertwined. She was raised to be the perfect embodiment of virtue, and died at the age of twenty-one, consumed by tuberculosis. In moments of ‘lucidity’ , she spoke of her suffering and that challenged the very foundations of Govardhanram’s life. In 1905 he wrote her biography, Lilavati Jivankala. This is a rare work in biographical literature, a father writing about the life of a deceased daughter. Despite Govardhanram’s attempts to contain Lilavati as a unidimensional figure of his imagination, she goes beyond that, sometimes by questioning the fundamental tenets of Brahminical beliefs, and at others by being so utterly selfless as to be unreal even to him.

So, with this breathtaking list in hand, let’s get travelling, shall we?