Dr.APJ Abdul Kalam’s benevolence and goodwill towards society is no news to us. The late President of India was a beautiful boon that mankind witnessed. His ‘Mission India : A Vision for Indian Youth’ addresses the youth in their endeavour to contribute to the nation’s progress. The book also plays an important role in that it tells every individual and organisation how they can shape and transform the nation by 2020.

Read the excerpt below to remember this amazing soul!

If you think about the development of human civilization, you will find that the pace of social and economic growth has been closely related to the proficiency with which people have been able to use the materials and chemicals in the world around them. In the beginning, this was through keen observation and trial and error. Thousands of years ago, men and women discovered, perhaps by accident, that they could hunt more easily if they sharpened rocks into weapons. They discovered that certain herbs helped to heal wounds. Once they discovered these properties of the materials around them, they remembered these and started using them. Their knowledge of these few things was slowly extended to others. As more and more knowledge was accumulated, human civilization as we know it today developed. Think about all the things you take for granted, as a normal part of life. Do you know it was only about two hundred

years ago that man started using coal and oil as energy sources to run machinery? The railways were invented. As a result, man could transport raw materials from far away to create new products and also sell them in distant places. It thus became very easy for goods to be transported, made easier still by the advent of the automobile and the aeroplane. Today, you can talk to people across the world from wherever you are—home, office, on a bus. But mobile phones were commercially available only from 1987. The first mobiles were available in India from 1994–95—and there were over 10 million users by 2002! Even something which seems as simple as a matchbox was only invented in the late nineteenth century—less than 120 years ago. Imagine how difficult it was to light a fire before that! Some ten years ago, the Internet became widely used. A vast world of information became available on the computer at the click of a mouse. As a result, knowledge flows so much easier. Sitting at your desk in India, you can find out about events and technologies all over the world. When I was writing this book, it was so much quicker for me to check the facts.

Ten years ago, it would have taken me ten times as long to write it, as I would have to go to many libraries and talk to many different people to get the same amount of information. The creation of so much technology is dependent on the creation of the advanced materials which are used to create computers, fibre optic cables, scanners and printers. Just imagine then, how different the world can be a hundred years from now! At the present rate of growth, in twenty years we can have trains that will travel from Delhi to Mumbai in a few hours—there is talk already of trains that can move as fast as planes using electromagnetic technology, robots in every home that can do the housework, and computers that will write down your homework as you talk! In this exciting world of rapid change, you have many wonderful opportunities to change the world and change India, if you can think out of the box and work with technology!

There are so many new materials available nowadays which our grandparents did not have access to. Our houses are full of modern materials: stainless steel, fibre glass, plastics, musical

and audio-visual materials. In the world outside, there are so many new materials as well: lightweight, high-performance alloys help us build aircraft, satellites, launch vehicles and

missiles and various kinds of plastics. Think of all the things in your daily life which are made of plastic—and imagine a world without them. The better use a country can make of its materials and chemicals, the more prosperous it will be. These new materials can also help in making life easier in ways that were not thought of when they were being invented. The DRDO has developed at least fifteen promising life science spin-off technologies from what were originally defence projects, some of them missile programmes.

You must have heard of Agni, India’s indigenously produced intermediate-range ballistic missile, first test-fired in May 1989. For Agni, we at the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO) developed a new, very light material called carbon-carbon. One day, an orthopaedic surgeon from the Nizam Institute of Medical Sciences in Hyderabad visited my laboratory. He lifted the material and found it so light that he took me to his hospital and showed me his patients—little girls and boys who had polio or other problems, as a result of which their legs could not function properly. The doctors helped them to walk in the only way they could—by fitting heavy metallic callipers on their legs. Each calliper weighed over 3 kg, and so the children walked with great difficulty, dragging their feet around. The doctor who had taken me there said to me, ‘Please remove the pain of my patients.’ In three weeks, we made these Floor Reaction Orthosis 300-gram callipers and took them to the orthopaedic centre. The children could not believe their eyes! From dragging around a 3-kg load on their legs, they could now move around freely with these 300-gram callipers. They began running around! Their parents had tears in their eyes. An ex-serviceman from a middle-class family in Karnataka wrote to us, after reading about how we had assisted polio-affected children. He inquired if something could be done for his twelve-year-old daughter who was suffering from residual polio of the leg and was forced to drag herself with a 4.5-kg calliper made out of wood, leather and metallic strips. Our scientists invited the father and daughter to our laboratory in Hyderabad, and together with the orthopaedic doctors at the Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences, designed a Knee Ankle Foot Orthosis weighing merely 400 grams. The girl’s walking almost returned to normal using this. The parents wrote to us a couple of months later that the girl had learned cycling and started going to school on her own.

Dr.Kalam contributed immensely to development of the nation. Purchase your copy to read more on the man and his extraordinary talent and achievement in the field of science, education, society and so on.

Tag: featured

There’s a New Boy In Nicky and Noni’s Class! Do They Become Friends? — ‘Being a Good Friend Is Cool’: An Excerpt

In Sonia Mehta’s Being a Good Friend Is Cool from her new series of books — My Book of Values, the author talks about the cool value of being a good friend.

Nicky and Noni have a new boy in class, but Nicky seems to be doing something wrong. What is it? Let’s find out!

What do Nicky and Noni do next? Do they become friends with Jojo? Grab a copy of Being a Good Friend is Cool to find out!

“We are never alone, are we?” An Excerpt from Shinie Antony’s ‘Boo’

Have you ever felt someone was watching you, even though you are all alone? Shinie Antony’s ‘Boo’ is a collection of thirteen well-crafted paranormal tales, each uniquely haunting in its own way. The stories penned by Shashi Deshpande, K.R. Meera, Jerry Pinto, Durjoy Datta, and many other illustrious names are sure to send a chill down your spine.

Here’s an excerpt of the introduction of the book.

The unknown has always beckoned. Infinite, cobwebby, black as the night, silent as the grave, what we cannot see hear touch. What, furthermore, is perhaps not alive.

My own experiences of the uncanny stay mine; fear takes me where it will. There were whispers without words and things I almost saw. And unlike what I always thought, squeamish as I am and lily-livered, these semi-happenings did not creep me out. Sometimes I saw them as other-worldly warnings, sometimes they were not meant to be seen and my eye had somehow breached a divide, sometimes my mouth formed words I did not mean to say . . .

The paranormal has many subgenres, but of these it was not the occult, poltergeists or screams of the possessed that brought me to these stories, but the psychological thrill. The mind is where it all begins. The mind is where it lives. This feeling that there’s something out there—and it is on to us. It knows that we know. And we must forever pretend we don’t know, not catch its eye—even when it is looking straight at us.

The gothic charm of K.R. Meera’s story, the sweet smell of onions in Kanishk Tharoor’s tale, the burden of hindsight in Shashi Deshpande’s mythofiction, the menacing narrator in Jerry Pinto’s story—they all bring in the supernatural slyly, stylishly. Durjoy Datta, Jahnavi Barua, Manabendra Bandyopadhyay, Kiran Manral and Jaishree Misra give us the old-fashioned traditional ghost story, the one where the banshee sighs or screams. While Ipsita Roy Chakraverti decodes a message from the beyond, Madhavi S. Mahadevan and Usha K.R. take us to places where the backstory is everything.

We wouldn’t be here—you reading this, me writing this—if we didn’t know. Despite science, reason and a raised eyebrow. Deep in our bones, when all falls silent, there is a knowing that precedes births and lingers after deaths. It lifts the hair at the nape of our neck; it stares at us, infatuated, from behind stairs; prescient, it invades our very rocking chair, replacing peace and calm with a restless zigzag; it rotates its head 360 degrees when we aren’t looking.

It doesn’t dispel though we move on, go our ways, live lives, love and let go. What is it that shifts just beyond our vision? Who listens when we talk in our heads? When does dark get just that little bit darker? Why that word on the billboard—the same word we just finished thinking about? And then bumping into the very person we thought of after a hundred years only that morning . . .

What do we know about ourselves besides incidents and milestones and birthdays and heartbreaks, what do we know of that which cannot be known? It is there in a photograph or painting you see—the feeling that you’ve been there before, seen that face somewhere. We are here but we are elsewhere too.

A haunting. Begins as a catch in the side, a stiff neck, a hunch, a bad feeling, pins and needles, an eye twitch, sleep talk, a leg gone numb, vertigo, spasms, heart that trebles its beat, a smell, a chill, a spell, a tingle, dreaming the same dream, a sudden vision of what’s to come, waking at 3.33 a.m., a song no one else can hear, the sound of breathing when we hold our breath . . .

We are never alone, are we?

10 Things You Should Know About Akash Verma

Akash Verma is a man of many talents. Not only is he a bestselling author but also an established entrepreneur. His profile lists him as the co-founder of two start-up companies before which he had also dabbled various roles in major corporations like Coca-Cola, Big FM and Red FM.

Akash is back with his fourth novel, You Never Know: Sometimes Love Can Drag You Through Hell…, a romance thriller which will keep you at the edge of your seat till the last page.

Here are a few things facts about the bestselling author.

Early beginnings!

Master of many talents

Woah!

It’s all in the genes.

Relate!

Quite a quirk that is…

The next time you want some gossip about the tinsel town, you know whom to turn to.

Wow!

Aww!

How many of these facts did you already know about the author?

When India defeated the English in 1911, An Excerpt from ‘Barefoot to Boots’

India’s association with football goes way back to the colonial times. Only a few may know that India was once called the ‘Brazil of Asia’ or that the rivalry between East Bengal and Mohun Bagan is included among the top fifty rivalries in club football around the world.

Renowned journalist, Novy Kapadia’s Barefoot to Boots reveals the glorious legacy of football in India. The book also offers valuable insight into the future of the sport in the country.

Here’s an exclusive excerpt from the book.

In 1910, the legendary Indian pehalwan, or wrestler, known as the ‘Great Gama’ was declared world champion (Rustom-e-Zamana) in freestyle wrestling. In front of a capacity crowd at the Shepherd’s Bush Stadium in London on 10 September, Gama dominated the bout of over two hours against reigning champion Stanislaus Zbyszko of Poland. The gigantic Zbyszko was on his feet only thrice in the entire bout. A return bout was scheduled a week later, and it was a walkover for Gama, who who were declared champions. The British celebrated Gama’s victory as the triumph of a British subject over an uppity European wrestler. Little did they know that their own supremacy would soon be challenged.

In 1911, Kolkata’s oldest Indian football club, Mohun Bagan, were invited to play in the prestigious IFA Shield. Coached by the disciplinarian Sailen Basu, the barefooted players had a great run in the tournament. They triumphed over St Xavier’s Institute 3-0 and Rangers FC 2-1 in the first and second rounds, defeated Rifle Brigade 1-0 in the quarter-final, and Middlesex Regiment 4-1 in the semi-final. They reached the final in top form.

The craze for the final was such that Mohun Bagan fans travelled to Kolkata from the outlying districts and from neighbouring Assam and Bihar. The East Indian Railway ran a special train for the purpose. Additional steamer services were also introduced to ferry spectators from rural areas to the ground. Tickets originally priced at Rs 1 and 2 were sold in the black market for Rs 15. Refreshment vendors too made good use of the opportunity. The total number of spectators in the final was estimated at 80,000–1,00,000. This was truly remarkable, as the population of Kolkata and its suburbs was then a little over 10 lakh.

The crowds were at fever pitch. Two sides of the ground were kept open for assembled spectators. Touts provided wooden boxes to help them get a view of the match and charged money per box, depending on its proximity to the playing area. There was no space even on treetops. The members’ seats were fully occupied and the enclosed side of the ground had been booked by B.H. Smith & Company for British fans. As many Bagan supporters did not have a good view of the match, volunteers devised an ingenious method to keep them informed of the progress of the game—they flew kites with the club’s colours and the score written on them. The final was goalless at half-time. Sergeant Jackson scored with about fifteen minutes left in the match. Mohun Bagan equalized immediately afterwards through skipper Shibdas

Bhaduri. The equalizer led to an explosion of kites in the sky, all coloured maroon and green. The burly centre-forward Abhilash Ghosh scored the winning goal. On 29 July 1911, Mohun Bagan made history by defeating a British regimental team East Yorkshire Regiment of Faizabad 2-1, and becoming the first Indian team to lift the coveted IFA Shield.

The victory established Kolkata as the nerve centre of football in India and heralded the city’s long-lasting love affair with football. It also had massive political and social implications. Coupled with Gama’s victory, Bagan’s win had exploded the myth that the British or Europeans were a superior race, something that the Congress Party and proponents of Swadeshi had been unable to do. The victory was seen as a symbol of hope for a subjugated nation.

It challenged the notion of Bengalis as an effeminate race and reconstructed a more masculine and sprightly image of them. Bagan’s historic win was chronicled in newspapers outside Kolkata (the Times of India, Mumbai, and the Pioneer, Lucknow) and internationally as well. It found mention in British newspapers—the Times, Daily Mail and the Manchester Guardian. The news agency Reuters reported it too.

The entire Mohun Bagan team played barefooted, which has led to the myth that boots cramped their style of play and playing barefoot improved ball control and dribbling skills. However, economic conditions are a more plausible reason for this. At the turn of the twentieth century, hand-sewn football boots cost Rs 7 and 4 annas, a lot of money in those days.

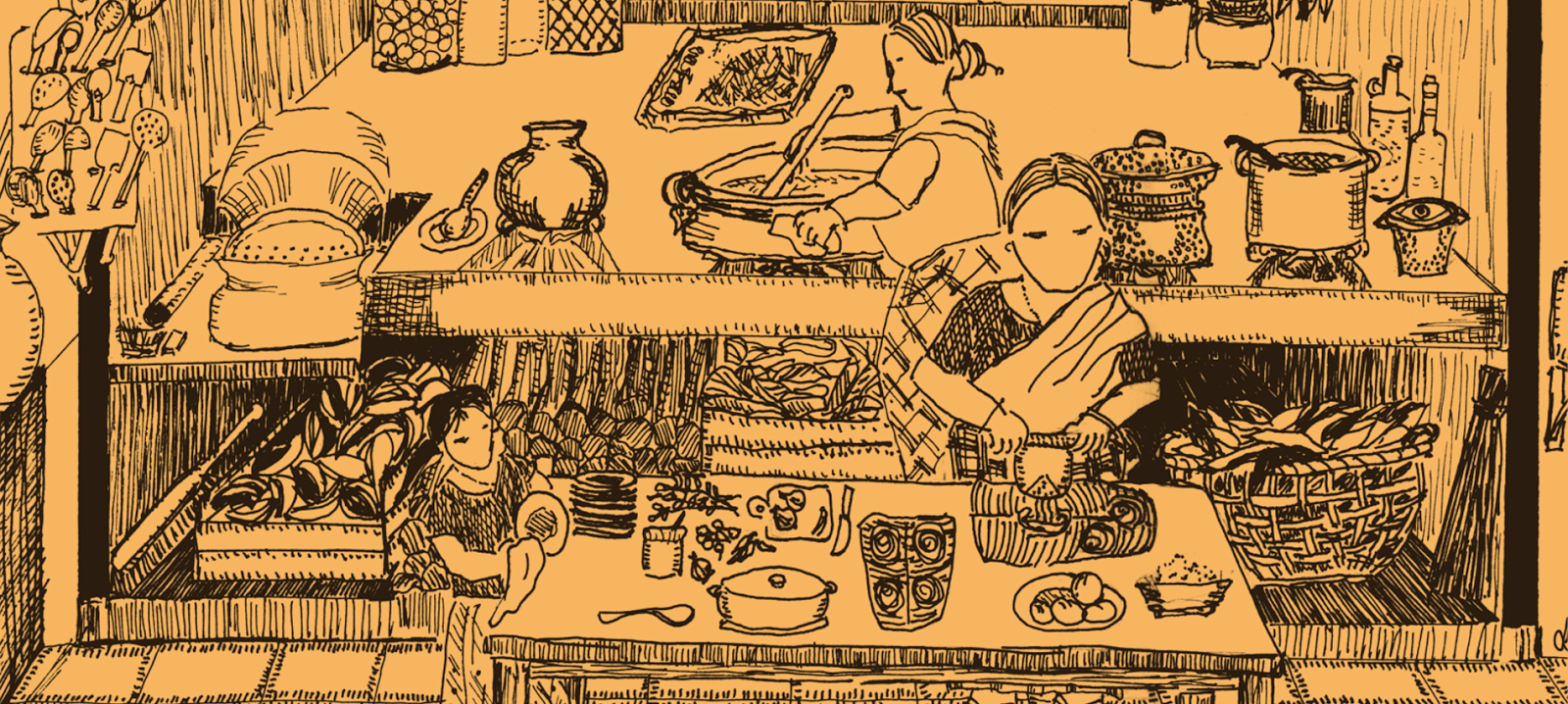

Cooking Tales From the ‘Suriani Kitchen’

The lure of spices has drawn all to Kerala since time immemorial. The vibrant Syrian Christian community of Kerala brings together not just a rich history, but an equally delightful assortment of flavors and aromas with its amazing culinary secrets.

Lathika George’s The Suriani Kitchen gives us a glimpse into the fascinating kitchen of the Syrian Christians of Kerala with their unique stories of cooking and mouth-watering dishes.

Here are a few snippets from the book.

Can’t wait to find out more from this gastronomic heaven? Get your copy today!

5 facts About the Father of our Nation You Should Know

Today marks the 148th birthday of Mahatma Gandhi, or as he was dearly addressed, Bapuji. The extraordinary figure he was, revered and followed by many, Bapuji followed a simple, ordinary lifestyle. His teachings on truth and nonviolence (ahimsa) inspired the masses in India’s freedom movement against the British Raj, and it continues to do so even now.

Here are a few facts about the man who changed the landscape of India forever.

Revelation!

Humble soul

Gandhiji understood the importance of self-sustenance

Gandhiji believed meditation was important for both body and mind

Kasturbaji died in prison, sent there with Gandhiji for civil disobedience

How many of these facts did you know about Bapu?

Excerpt 3: ‘Origin’ by Dan Brown – Chapter 1 (Continued)

About a year ago, Kirsch had surprised Langdon by asking him not about art, but about God—an odd topic for a self-proclaimed atheist. Over a plate of short-rib crudo at Boston’s Tiger Mama, Kirsch had picked Langdon’s brain on the core beliefs of various world religions, in particular their different stories of the Creation.

Langdon gave him a solid overview of current beliefs, from the Genesis story shared by Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, all the way through the Hindu story of Brahma, the Babylonian tale of Marduk, and others.

“I’m curious,” Langdon asked as they left the restaurant. “Why is a futurist so interested in the past? Does this mean our famous atheist has finally found God?”

Edmond let out a hearty laugh. “Wishful thinking! I’m just sizing up my competition, Robert.”

Langdon smiled. Typical. “Well, science and religion are not competitors, they’re two different languages trying to tell the same story. There’s room in this world for both.”

After that meeting, Edmond had dropped out of contact for almost a year. And then, out of the blue, three days ago, Langdon had received a FedEx envelope with a plane ticket, a hotel reservation, and a handwritten note from Edmond urging him to attend tonight’s event. It read: Robert, it would mean the world to me if you of all people could attend. Your insights during our last conversation helped make this night possible.

Langdon was baffled. Nothing about that conversation seemed remotely relevant to an event that would be hosted by a futurist.

The FedEx envelope also included a black-and-white image of two people standing face-to-face. Kirsch had written a short poem to Langdon.

Robert,

When you see me face-to-face,

I’ll reveal the empty space.

—Edmond

Langdon smiled when he saw the image—a clever allusion to an episode in which Langdon had been involved several years earlier. The silhouette of a chalice, or Grail cup, revealed itself in the empty space between the two faces.

Now Langdon stood outside this museum, eager to learn what his former student was about to announce. A light breeze ruffled his jacket tails as he moved along the cement walkway on the bank of the meandering Nervión River, which had once been the lifeblood of a thriving industrial city. The air smelled vaguely of copper.

As Langdon rounded a bend in the pathway, he finally permitted himself to look at the massive, glimmering museum. The structure was impossible to take in at a glance. Instead, his gaze traced back and forth along the entire length of the bizarre, elongated forms.

This building doesn’t just break the rules, Langdon thought. It ignores them completely. A perfect spot for Edmond.

The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, looked like something out of an alien hallucination—a swirling collage of warped metallic forms that appeared to have been propped up against one another in an almost random way. Stretching into the distance, the chaotic mass of shapes was draped in more than thirty thousand titanium tiles that glinted like fish scales and gave the structure a simultaneously organic and extraterrestrial feel, as if some futuristic leviathan had crawled out of the water to sun herself on the riverbank.

When the building was first unveiled in 1997, The New Yorker hailed its architect, Frank Gehry, as having designed “a fantastic dream ship of undulating form in a cloak of titanium,” while other critics around the world gushed, “The greatest building of our time!” “Mercurial brilliance!” “An astonishing architectural feat!”

Since the museum’s debut, dozens of other “deconstructivist” buildings had been erected—the Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, BMW World in Munich, and even the new library at Langdon’s own alma mater. Each featured radically unconventional design and construction, and yet Langdon doubted any of them could compete with the Bilbao Guggenheim for its sheer shock value.

As Langdon approached, the tiled facade seemed to morph with each step, offering a fresh personality from every angle. The museum’s most dramatic illusion now became visible. Incredibly, from this perspective, the colossal structure appeared to be quite literally floating on water, adrift on a vast “infinity” lagoon that lapped against the museum’s outer walls.

Langdon paused a moment to marvel at the effect and then set out to cross the lagoon via the minimalist footbridge that arched over the glassy expanse of water. He was only halfway across when a loud hissing noise startled him. It was emanating from beneath his feet. He stopped short just as a swirling cloud of mist began billowing out from beneath the walkway. The thick veil of fog rose around him and then tumbled outward across the lagoon, rolling toward the museum and engulfing the base of the entire structure.

The Fog Sculpture, Langdon thought.

He had read about this work by Japanese artist Fujiko Nakaya. The “sculpture” was revolutionary in that it was constructed out of the medium of visible air, a wall of fog that materialized and dissipated over time; and because the breezes and atmospheric conditions were never identical one day to the next, the sculpture was different every time it appeared.

The bridge stopped hissing, and Langdon watched the wall of fog settle silently across the lagoon, swirling and creeping as if it had a mind of its own. The effect was both ethereal and disorienting. The entire museum now appeared to be hovering over the water, resting weightlessly on a cloud—a ghost ship lost at sea.

Just as Langdon was about to set out again, the tranquil surface of the water was shattered by a series of small eruptions. Suddenly five flaming pillars of fire shot skyward out of the lagoon, thundering steadily like rocket engines that pierced the mist-laden air and threw brilliant bursts of light across the museum’s titanium tiles.

Langdon’s own architectural taste tended more to the classical stylings of museums like the Louvre or the Prado, and yet as he watched the fog and flame hover above the lagoon, he could think of no place more suit- able than this ultramodern museum to host an event thrown by a man who loved art and innovation, and who glimpsed the future so clearly.

Now, walking through the mist, Langdon pressed on to the museum’s entrance—an ominous black hole in the reptilian structure. As he neared the threshold, Langdon had the uneasy sense that he was entering the mouth of a dragon.

——-

Origin by Dan Brown Releases on October 3’ 2017.

Preorder your copy today!

The Simple Messages Hidden in ‘Mahabharata’: ‘The Boys Who Fought’

The story of Mahabharata has been retold countless times through generations and one instinctively comes to identify it with the great battle of Kurukshetra.

But going beyond all the animosity and rivalry that overarches the epic, Mahabharata espouses some important messages for life, an aspect Devdutt Pattanaik has brought forth for us in The Boys Who Fought.

Here are a few times we were reminded of the simple but impactful messages from the Mahabharata that transcend time and remain equally relevant even today.

When Vyasa wondered about the progress humankind had truly made.

When Ekalavya showed us the meaning of control, as opposed to destruction.

When we were reminded of the true meaning of ‘life’.

When we were told about the vicious cycles humankind gets trapped in.

Know more about the timeless messages of the Mahabharata with Devdutt Pattanaik’s beautifully illustrated book today!

‘We Don’t Really Know Fear’: ‘India’s Most Fearless’: An Excerpt

The Army major who led the legendary September 2016 surgical strikes on terror launch pads across the LoC; a soldier who killed 11 terrorists in 10 days; a Navy officer who sailed into a treacherous port to rescue hundreds from an exploding war; a bleeding Air Force pilot who found himself flying a jet that had become a screaming fireball . . .

India’s Most Fearless is a collection of their own accounts or of those who were with them in their final moments.

Here’s an excerpt from Chapter 1 of the book ‘We Don’t Really Know Fear’ :The September 2016 Surgical Strikes in PoK

—-

Uri, Jammu and Kashmir 18 September 2016

Final checks on the AK-47 rifles. Final checks on the stacks of ammunition magazines and grenades stuffed into olive-green knapsacks. The 4 men shoved fistfuls of almonds into their mouths, chewing quickly in the darkness and swallowing. Small, light and packed with a burst of energy, mountain almonds are as much a staple for terrorist infiltrators as their weapons are. The high-protein mouthfuls would have to sustain the 4 men for the next 8 hours.

At least 8 hours.

Dressed in deceptive Indian Army combat fatigues, and shaven clean to blend in, the 4 emerged from their concealed launch point below a ridgeline overlooking a stunning expanse of frontier territory. In total darkness, they trekked for 1 km down to the powerfully guarded premises of the Indian Army’s Uri Brigade in Jammu and Kashmir’s Uri sector, on the LoC.

The 4 men knew their mission was not particularly extraordinary. Indian military facilities had been attacked by Pakistani terrorists before. In fact, just 8 months earlier, in January 2016, an identical number of terrorists had infiltrated the Indian Air Force’s base in Pathankot, where they had managed to kill 7 security personnel before being eliminated.

But there was something these men did not know. What they were about to do would change India like nothing else had in the past quarter century. It would compel India across a military point of no return that it had resisted until then.

Above all, it would awaken a monster that Pakistan had been arrogantly certain would remain in eternal slumber.

Infiltrating the Army camp at Uri before sunrise, the 4 men crept forward with an unusual sense of familiarity. Their Pakistani handlers had clearly ‘war-gamed’ the attack with maps and models of the camp. Wasting no time in familiarizing themselves with the camp’s layout, they headed straight for a group of tents where the soldiers were sleeping.

By the time the sun was fully up and Special Forces (SF) commandos had been diverted to Uri as reinforcements, 17 Indian soldiers lost their lives. Two more would die later in hospital.

In a valley that has steadily numbed India with uninterrupted spillage of blood, the Uri terror ambush was special. Other than the horrifying scale of casualties the 4 terrorists managed to achieve, it was the hubris of the Uri attack that ignited unprecedented anger. It had come while families still mourned those who had died defending the Pathankot Air Force base only 8 months before.

Like the 4 terrorists, Pakistan was probably confident that India’s ensuing wrath would be confined to public outrage and diplomatic condemnations, a standardized matrix of responses that it had learnt to handle with mastery. But Pakistan did make 1 devastating miscalculation. India was about to use precisely its reputation for inaction to exact a hitherto unthinkable revenge.

As blanket coverage of the Uri attack took over television news and the Internet on the morning of 18 September, a chill descended upon India’s Raisina Hill in Delhi. Emergency meetings were held in the most secret ‘war rooms’ of the security establishment, one of them presided over by Prime Minister Narendra Modi along with National Security Adviser Ajit Doval.

It was at this meeting that the Indian leadership secretly took 2 major decisions: (1) the Indian military would take the fight to the enemy this time to deliver a brutal response to the Uri attack; (2) the country’s ministers, including Modi himself, would play their parts to perpetuate and amplify India’s reputation for inaction until such a time when the response had been delivered. An elaborate, carefully crafted political masquerade would thus begin the following morning.

Meanwhile, 800 km away and high up in the Himalayas, a young Indian Army SF officer sat grimly in front of a small television in his barracks. Uri was his area. His hunting ground. Away on a special 2-month mission to the Siachen Glacier with a small team of men from his unit, the calm of Maj. Mike Tango’s demeanour belied the fury that consumed him within. He watched familiar pictures from the Uri Army camp flicker on the screen in front of him. And just as the Indian government was about to decide on an unprecedented course of action, a prescient warning rang in the Major’s mind.

‘We knew the balloon had gone up. This wasn’t a small incident. There was no question of sitting silent. This was beyond breaking point,’ he says.

As second-in-command, or 2IC, of an elite Parachute Regiment (Special Forces), or the Para-SF as it is called, Maj. Tango had spent a decade of his 13 service years in J&K. He had been part of over 20 successful antiterror operations. And yet, the morning of 18 September had sent a knife through the officer’s heart. He could not wait to get back to the rest of his unit deployed in and around where the terrorists had struck.

Upon receiving the call from Udhampur that he had been expecting, from his unit’s Commanding Officer, or CO, Maj. Tango gathered his men immediately for a quick return to the Valley. The team reached Dras that same night of 18 September—a date the men would never forget.

The next morning, as they began their journey to Srinagar, things were already in motion in Delhi. The first minister to make a statement was former Army Chief, Gen. V.K. Singh, who, after the traditional condemnations, made a remarkably generous appeal in the circumstances—he said that India could not act on emotion. It would be a critical spark to the success of the masquerade, followed shortly thereafter by Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar, who declared that the sacrifice of the Uri soldiers would not go in vain. Speaking to the Army in Srinagar, Parrikar sounded a familiar note, asking the Army to take ‘firm action’, but not specifying what such action needed to be. This was standard-issue Bharat Sarkaar (Indian Government) response after a terror attack.

However, to ensure that the government’s messaging was not so measured as to rouse suspicion, junior ministers were tasked with adding some fire to the proceedings. That crucial bit was deftly served up by Manohar Parrikar’s junior minister, Subhash Bhamre, who declared that the time had come ‘to hit back’.

Two more top-level meetings took place on 19 September— one chaired by Home Minister Rajnath Singh, who had cancelled his visit to Russia, and the other by Prime Minister Modi at the PMO. Army Chief Gen. Dalbir Singh, who had dashed to the Kashmir valley just hours after the previous day’s attack, had been conveyed the government’s clear political directive. He arrived in Srinagar with the green signal that the SF had so far only ever dreamt about: permission to plan and execute a retaliatory strike with the government’s full backing.

Over the next 24 hours, the Army would draw up a devastating revenge plan, with options for the government leadership to choose from.

The Army routinely simulates attacks on enemy territory during combat exercises and as preparation for possible hostilities. But as the COs of the 2 SF units (one of them being Maj. Tango’s unit) began listing their options, they knew that history was being written then and there.

On 20 September, just as Maj. Tango and his team arrived in Srinagar, the Army’s Northern Commander, or GOC-in-C of the Udhampur-headquartered Northern Command, Lt. Gen. Deependra Singh Hooda, had in his hands a final list of mission options and was preparing to present them to the government in Delhi through encrypted channels. The options were presented with remarkable detail.

‘We just needed clearance. In the SF, we are war-ready at all times. When we are not in operations, we are preparing for them. There’s a purpose behind everything we do,’ Maj. Tango says.

At the Army Headquarters in Delhi, the mood was expectedly sombre, but focused. Aided by a team that had been galvanized by the attack, Vice Chief of the Army Staff (later Chief) Lt. Gen. Bipin Rawat was steeped in the planning phase, bringing decades of infantry training to what would be the most decisive operation he would help oversee. What happened on 18 September was personal for Lt. Gen. Rawat. As a young Captain, he had commanded a Gorkha Rifles company in Uri in the early 1980s and had gone on to command a brigade in one of the most restive parts of the Kashmir valley. He would return years later as a Major General to command the Baramulla-based 19 Division. As he focused on the unprecedented plans on his table, Lt. Gen. Rawat had no way of knowing that a few months later, his experience in J&K and his crucial role in planning India’s response to Uri would be high on the government’s mind when it entrusted him with leadership of one of the largest armies in the world.

(Continued…)