India’s journey to Independence is a story of courage, sacrifice, and unwavering resolve, led by extraordinary individuals who shaped the nation’s destiny. As we reflect on their contributions, these 17 books delve deep into the lives of the brave souls who fought for our country, uncovering the true cost of our hard-earned freedom.

Find inspiration in their patriotism, vision, and enduring legacy, which continues to guide and uplift us as a nation even today!

Before Mahatma Gandhi, there was Bal Gangadhar Tilak – the revolutionary who ignited the spark of Indian nationalism. The Times, London, called him ‘the father of Indian unrest,’ and the one-time Secretary of State for India Edward Montagu felt he had ‘the greatest influence of any person’ on the Indian people. Above all, for the British Raj, Tilak was sedition-monger-in-chief, and it prosecuted him thrice for sedition.

Rediscover an icon of Indian history whose ideas and actions continue to resonate today. Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s story is not just a tale of resistance but a testament to perseverance and conviction.

Meticulously researched and eloquently written, Being Hindu, Being Indian offers the first comprehensive examination of Lajpat Rai’s nationalist thought. By revealing the complexities of Rai’s thinking, it provokes us to think more deeply about broader questions relevant to present-day politics: Are all expressions of ‘Hindu nationalism’ the same as Hindutva? What are the similarities and differences between ‘Hindu’ and ‘Indian’ nationalism? Can communalism and secularism be expressed together? How should we understand fluidity in politics? This book invites readers to treat Lajpat Rai’s ideas as a gateway to think more deeply about history, politics, religious identity and nationhood.

There are not many Indian heroes whose lives have been as dramatic and adventurous as that of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. That, however, is an assessment of his life based on what is widely known about him. These often revolve around his resignation from the Indian Civil Service, joining the freedom movement, to be exiled twice for over seven years, throwing a challenge to the Gandhian leadership in the Congress, taking up an extremist position against the British Raj, evading the famed intelligence network to travel to Europe and then to Southeast Asia, forming two Governments and raising two armies and then disappearing into the unknown. All this in a span of just two decades.

Pacey, thought-provoking and absolutely unputdownable, Bose: The Untold Story of an Inconvenient Nationalist will open a window to many hitherto untold and unknown stories of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose.

In The Foresighted Ambedkar, Anurag Bhaskar argues that India’s Constitution was drafted not just between 1946 and 1950 but over the course of four decades. Dr Ambedkar was the only person to have been involved at all the stages related to the drafting of the Indian constitutional document since 1919. These stages bear the imprint of his contribution and role.

In 1871, the British enacted the Criminal Tribes Act in India, branding numerous tribes and caste groups as criminals. In This Land We Call Home, Nusrat F. Jafri traces the roots of her nomadic forebears, who belonged to one such ‘criminal’ tribe, the Bhantus from Rajasthan.

This affecting memoir explores religious and multicultural identities and delves into the profound concepts of nation-building and belonging. Nusrat’s family found acceptance in the church, alongside a sense of community, theology, songs and carnivals, and quality education for the children in missionary schools.

It is rare to see a lawyer from a district court occupy centre stage in the Supreme Court but M.K. Nambyar achieved this remarkable feat. Starting his practice in a district court in Mangalore, M.K. Nambyar rose to become an eminent constitutional lawyer. Written by his son K.K. Venugopal, a legal luminary himself, this biography provides a fascinating account of Nambyar’s life. It not only describes the man but also recapitulates India’s legal history from the pre-Independence era. The book includes some landmark cases argued by Nambyar that have significantly contributed to the development of constitutional law in India such as A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras and I.C. Golak Nath v. State of Punjab, where he sowed the seeds of the ‘basic structure’ doctrine. These cases continue to guide and inspire lawyers and judges today.

Winston Churchill was closely connected with India from 1896, when he landed in Bombay with his regiment, until 1947, when Independence was finally achieved. No other British statesman had such a long association with the subcontinent—or interfered in its politics so consistently and harmfully.

Churchill strove to sabotage any moves towards Independence, crippling the Government of India Act over five years of dogged opposition to its passage in the 1930s. As prime minister during the Second World War, Churchill frustrated the freedom struggle from behind the scenes, delaying Independence by a decade. To this day for Indians, he is the imperialist villain, held personally responsible for the Bengal Famine of 1943.

This book reveals Churchill at his worst: cruel, obstructive and selfish. However, the same man was outstandingly liberal at the Colonial Office, risking his career with his generosity to the Boers, the Irish and the Middle East. Why was he so strangely hostile towards India?

Jawaharlal Nehru was Plato’s philosopher king, who ‘discovered’ an India that remains an undiscovered possibility. Nehru and the Spirit of India is a critical and nuanced perusal of his intellectual and political legacy.

From the ‘politics of friendship’ between Nehru and Sheikh Abdullah, Nehru’s defense of secularism in the Constituent Assembly Debates, to what propelled Nehru to curb free speech in the First Amendment, Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee draws from political history to illuminate fierce debates in India today: Kashmir, the CAA, and hate speech. Be it contemporary events like the miracle of Ganesha drinking milk and the use of Vedic astrology in Chandrayaan-2, or the agonising suicide of a doctor, the author examines the fractured nature of Indian modernity, which Nehru had suggestively called a ‘garb’. Bhattacharjee bolsters Nehru’s view that India is enriched by the encounter of cultures and that we must not discard the past, but engage with it.

Jawaharlal Nehru wrote the book ‘The Discovery of India’, during his imprisonment at Ahmednagar fort for participating in the Quit India Movement (1942 – 1946). The book was written during Nehru’s four years of confinement to solitude in prison and is his way of paying an homage to his beloved country and its rich culture.

The book started from ancient history, Nehru wrote at length of Vedas, Upanishads and textbooks on ancient time and ends during the British raj. The book is a broad view of Indian history, culture and philosophy, the same can also be seen in the television series. The book is considered as one of the finest writing om Indian History. The television series Bharat Ek Khoj which was released in 1988 was based on this book.

History has always been the handmaiden of the victor. ‘Until the lions have their own storytellers,’ said Chinua Achebe, ‘the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter!’ Exploring the lives, times and works of the fifteen long-forgotten and mostly neglected unsung heroes and heroines of our past, this book brings to light the contribution of the warriors who not only donned armour and burst forth into the battlefield but also kept the flame of hope alive under adverse circumstances.

Pacy and unputdownable, Bravehearts of Bharat chronicles the stories of courage, determination and victory, which largely remained untold and therefore unknown for a long time.

Gandhi’s Assassin: The Making of Nathuram Godse and His Idea of India lays bare Godse’s relationship with the organizations that influenced his world view and gave him a sense of purpose. The book draws out the gradual hardening of Godse’s resolve, and the fateful decisions and intrigue that eventually led to, in the chaotic aftermath of India’s independence in 1947, Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination. On a wintry Delhi evening on 30 January 1948, Godse shot Gandhi at point-blank range, forever silencing the great man. Godse’s journey to this moment of international notoriety from small towns in western India is, by turns, both riveting and wrenching.

Drawing from previously unpublished archival material, Jha challenges the sanitization of Gandhi’s assassination, and offers a stunning view on the making of independent India.

Driven by the urge for complete freedom from colonialism, authoritarianism, fascism and militarism, which are rooted in the idea and politics of the nation-state, Acharya fought for an international vision of socialism and freedom. During the tumultuous opening decades of the 1900s—marked by the globalization of radical inter-revolutionary struggles, world wars, the rise of communism and fascism, and the growth of colonial independence movements—Acharya allied himself with pacifists, anarchists, radical socialists and anti-colonial fighters in exile, championing a future free from any form of oppression, whether by colonial rulers or native masters. Drawing on a wealth of archival material, private correspondence and other primary sources, Laursen demonstrates that, among his contemporaries, Acharya’s turn to anarchism was unique and pioneering in the struggle for Indian independence.

Anarchy or Chaos is the first comprehensive study of M. P. T. Acharya. It offers a new understanding of the global and entangled history of anarchism and anti-colonialism in the first half of the twentieth century.

The continual tussles over Bhagat Singh’s identity, even more amplified of late, are a testament to the heroic status the man continues to hold in the annals of the Indian freedom struggle. Despite him having addressed his views on religion, politics and activism, there are many willing to forge completely new narratives of his life, and many more willing to believe them.

A timely antidote, this meticulously researched biography is an expansive foray into the life of Bhagat Singh. The volume deliberates upon his family from before when he was born, examining along the way the role that various episodes, policies and people played in shaping the identity of a legendary revolutionary, while also delving into his opinions on important questions of the time. It shines a bright light on the oft-ignored personal influences that made Singh who he was, along with the issue of his contested identity in today’s politics. This is the definitive Bhagat Singh biography of our times.

Anecdotal, candid and evocative, Kitne Ghazi Aaye, Kitne Ghazi Gaye brings to light the true stories from this Army veteran’s life. It focuses on the personal, professional and, most importantly, family life of a soldier in the Army, and will not only provide an insight into the trials and tribulations he faced but will also inspire a wide spectrum of readers, especially young defence aspirants.

Bipin: The Man behind the Uniform is the story of the NDA cadet who was relegated in the third term for not being able to do a mandatory jump into the swimming pool; of the young Second Lieutenant who was tricked into losing his ID card at the Amritsar railway station by a 5/11 Gorkha Rifles officer posing as his sahayak; of the Major with a leg in plaster who was carried up to his company post on the Pakistan border because he insisted on joining his men for Dusshera celebrations under direct enemy observation; of the Army Chief who decided India would retaliate immediately and openly to every act of cross-border terrorism; of the Chief of Defence Staff who was happiest dancing the jhamre with his Gorkha troops.

In 1929, Bhagat Singh surrenders after a daring bomb attack in the heart of Delhi’s assembly. Behind bars, he prepares for an ideological battle against the empire. However, a shocking betrayal shatters his world.

Phanindra Nath Ghosh, a trusted comrade, becomes a British approver, revealing every secret of the HSRA. His damning testimony leads to multiple arrests, and then the British hang Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdeo. Popularly known as the ‘king’s witness’, he had singlehandedly brought on an armed revolution.

But with their leaders gone and British oppression at its peak, surviving HSRA members rally around one burning desire: revenge. Their target is the man who dismantled their life’s work. But with limited resources, their hopes rest on a lone figure.

From the shadows emerges Baikunth Sukul, an unassuming teacher and devoted admirer of Bhagat Singh. He swears to exact revenge on behalf of the martyrs and the HSRA.

Will he succeed in this nearly impossible mission?

What happens when he locks horns with the formidable British Raj?

And to what lengths will he go to avenge Bhagat Singh’s death?

India’s journey to Independence was filled with deeds of forgotten heroes. This is one such story of sacrifice and revenge—of a patriot against a traitor, a common man against the empire.

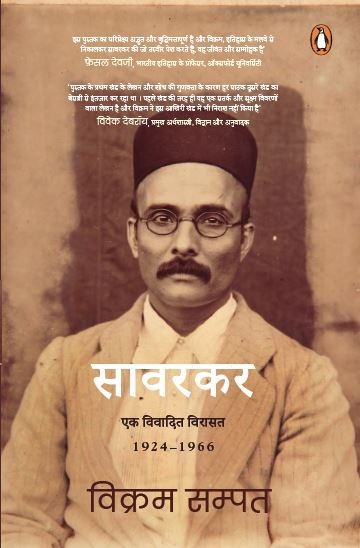

Decades after his death, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar continues to uniquely influence India’s political scenario. An optimistic advocate of Hindu-Muslim unity in his treatise on the 1857 War of Independence, what was it that transformed him into a proponent of ‘Hindutva’? A former president of the All-India Hindu Mahasabha, Savarkar was a severe critic of the Congress’s appeasement politics. After Gandhi’s murder, Savarkar was charged as a co-conspirator in the assassination. While he was acquitted by the court, Savarkar is still alleged to have played a role in Gandhi’s assassination, a topic that is often discussed and debated.

In this concluding volume of the Savarkar series, exploring a vast range of original archival documents from across India and outside it, in English and several Indian languages, historian Vikram Sampath brings to light the life and works of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, one of the most contentious political thinkers and leaders of the twentieth century.