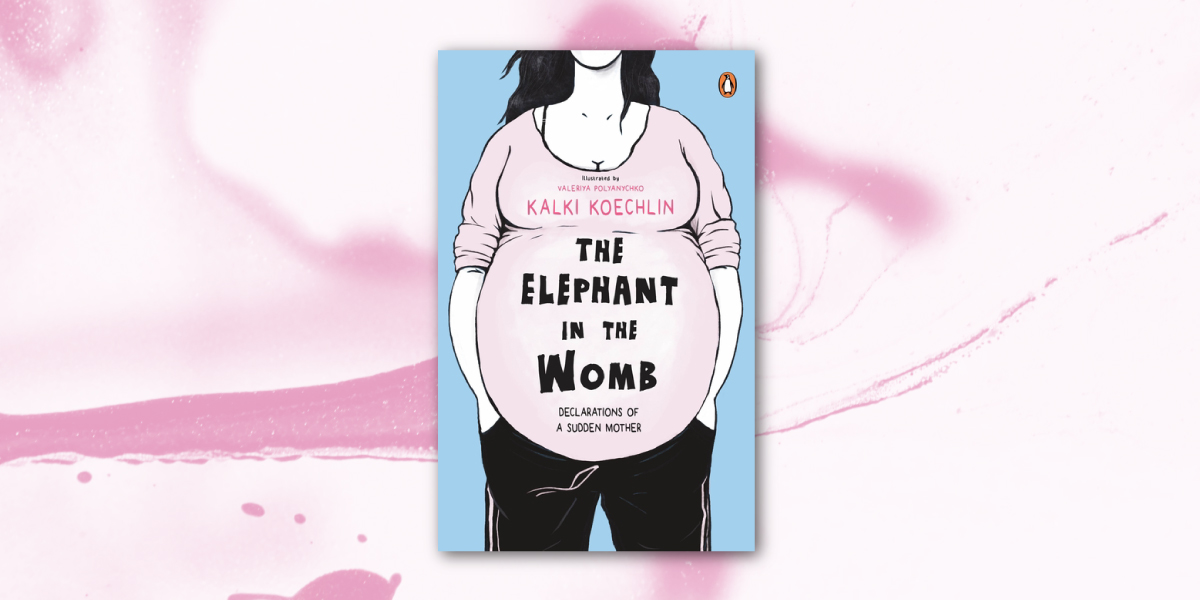

Parenthood is a challenging process, no matter who you are. Ask actress Kalki Koechlin!

In her graphic narrative The Elephant in the Womb, Kalki records the physical, mental, and emotional reckonings that she and her partner had to face, before and after childbirth. While archiving these raw feelings, she manages to bust a lot of myths surrounding pregnancy. Below are some of the many myths that the author dismantles while experiencing childbirth for the first time.

Myth 1: Miscarriages should not be talked about

Kalki starts her memoir right off the bat with a crucial point: miscarriage is not a matter of shame. It can feel tragic, can trigger grief and depression, but the guilt and shame are aggravated by treating miscarriage itself like a myth. 1 in 4 pregnancies experience a miscarriage, and most women experience this in the first trimester itself. Because most people hush it up and bring up other superstitions like the evil eye, the psychological effects of miscarriage are often felt by the mother, all by herself.

Myth 2: Pregnant women should restrict their movements

It doesn’t take long for people to change their behaviour around pregnant women, and The Elephant in the Womb describes this in fun, illustrative anecdotes. Once Kalki got pregnant, people around her began treating her like a porcelain doll, ready to break. When in fact, she wanted nothing more than to still hang out with friends and socialize! This myth is harmful especially because pregnant women need exercise in preparation for childbirth.

Myth 3: ‘Standard Procedure’ should be followed

The medical routines and processes which most expecting mothers are told are ‘standard procedure’, are sometimes myth. With the help of other mothers’ anecdotes, Kalki quickly realizes that she gets to decide how her body should be treated during her pregnancy. From discovering that anomaly scans are not mandatory to choosing both a doula as well as a gynaecologist for advice, Kalki establishes boundaries early on in her pregnancy. Most pregnant women let go of the authority of this process, often falling victim to unnecessary invasive procedures, not knowing that they are most likely to know what is best for their body.

Myth 4: Maternal instinct

Haven’t we all grown up hearing ‘mommy knows best’? Every mother has experienced being a mother for the first time, which means that making mistakes, looking out for support, having more people involved with the care of the baby is not an option but crucial for the mother’s physical and mental wellness. With postpartum depression being a real issue, it is unfair that women are expected to magically know and take care of all the affairs of the home after such a life-changing event.

The Elephant in the Womb is a unique graphic memoir that creatively expresses the hopes and anxieties of a modern mother in an ever-changing world.