Bimal Jalan had a close view of financial governance while he served as Union Finance Secretary and Governor of the Reserve Bank of India. Drawing on his vast experience he compares two distinct periods: 1980–2000 and 2000–15, and examines the transition India has made in the last four decades from a strictly regulated, slow-growth state enterprise to one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

In his latest book, India: Priorities for the future he lists out few areas India needs to pay attention to.

Here is a list of ten of those priorities:

One of the foremost priorities regarding financial governance

Priority for the banking sector

Another reform in the financial sector that the India has to bring about

The RBI has to keep working with financial experts to develop procedure for the debt markets to grow

The outcomes of the present schemes in terms of actual benefits is pretty low

Performance reviews of a ministry will lead to better execution of policies

Red tapism needs to be done away with

Outsourcing to different agencies reduces petty corruption and delays

An urgent political reform is to speed up investigations of persons who are in political parties

An utmost priority lies in making the states accountable for policy execution than the Centre

Which priority according to you should be the India’s topmost priority? Tell us.

Tag: india

India Transformed — An Excerpt

Rakesh Mohan is the former deputy governor of the RBI. He has also served as the executive director of the IMF and secretary, Department of Economic Affairs, and Ministry of Finance. He is currently a Distinguished Fellow with Brookings India.

India underwent a major economic reform in the form of liberalization in 1991. In India Transformed, India’s top business leaders and economists come together and provide a balanced picture of the consequences of the economic reforms, initiated in 1991. They ask themselves some imperative questions: What were the reforms? What were they intended for? How have they affected the overall functioning of the economy?

Here is an exclusive excerpt from the foreword of the book, written by Strobe Talbott, the former Deputy Secretary of United States of America.

This timely, authoritative and policy-relevant volume sheds light on India’s dramatic changes over the past quarter century. That transformation has not only been a boon to the people of India, it has also contributed to the progress of the human enterprise as a whole. The world’s largest democracy is a major player on the world stage. It is certainly viewed and valued that way by my own country, the United States of America.

The economic and commercial dimension of India’s evolution is, of course, crucial. Hence, the focus of submissions in the pages that follow is political economy, financial development, trade and globalization, technology and innovation, agricultural and industrial development, and the interaction between the private and public sectors. The contributors include some of the original designers and implementers of the reform process, along with the prominent business leaders who have been the most successful builders of the economy.

There is also, thanks to the inclusion of wisdom from Shivshankar Menon, Shyam Saran and Sanjaya Baru, due attention paid to India’s foreign and security policy.

Over the course of the last half-century, I have had numerous opportunities to watch India’s evolution, first from the vantage point of a student of international relations and then for two decades as a journalist. During my eight years in government during the 1990s, I also had a chance to participate in the effort by the Indian and the US governments to put the bilateral relationship on a sounder—indeed, a transformed—footing than had been the case in the first four decades after Indian Independence. Dennis Kux captured the perception on both sides of that star-crossed backstory in the subtitle of his 1992 book, India and the United States: Estranged Democracies.

What stymied a robust bond between these two countries? After all, both had wrested their independence from British rule while adopting and adapting many of the features of British constitutional governance (minus, of course, the monarchy).

The key factor, I’ve always believed, was the Cold War.

It was approximately at the midpoint of that global schism that I first visited India forty-two years ago. I owe that enriching and informative experience to a glitch in my career as a Sovietologist.

In those days, I was a reporter for Time magazine concentrating on East–West relations and was assigned to the State Department beat. This often meant whirling around the world, coping with what seemed like a permanent case of jetlag, trying to keep up with the then secretary of state Henry Kissinger.

In October 1974, Kissinger embarked on a seven-nation diplomatic tour starting with Moscow. The Kremlin was eager to welcome the secretary of state as the personification of continuity in the US policy of détente, in the wake of Richard Nixon’s resignation and Gerald Ford’s ascension to the presidency. The Soviets, however, were not about to extend their hospitality to me. I was persona non grata because of my role in translating and editing Nikita Khrushchev’s memoirs. The material for the two volumes was surreptitiously recorded and spirited out of the country while he was under virtual house arrest, since his ouster from the leadership ten years before. The second volume, published earlier in 1974, particularly irked Foreign Minister Anatoly Gromyko, who sent a message to Kissinger’s plane over the Atlantic, denying me a visa.

After I was unceremoniously dropped off in Copenhagen during a fuelling stop, I hopscotched to New Delhi, which would be Kissinger’s second stop after Moscow.

On the personal front, my several days of free time were immensely gratifying. I made friendships that lasted for decades. I also came to know Ambassador Daniel Patrick Moynihan (whose desk officer at the State Department was none other than Dennis Kux). Moynihan’s wife, Elizabeth, took me under her wing and drove me out to—where else?—the Taj Mahal, where she was already deeply into studying the Mughal gardens.

Trump and Modi: Strangely Silent on the US-India Nuclear Deal

By Larry Pressler

Larry Pressler was the chairman of the US Senate’s Arms Control Subcommittee and advocated the now-famous Pressler Amendment. His book Neighbours In Arms provides a comprehensive account of how US foreign policy in the subcontinent was formed from 1974 till today and ends with recommendations of a new US-India alliance that could be a model for American allies in future.

Here’s a piece written by him on the US-India nuclear deal.

When I first visited India in 1965, I was enthralled by the people, the food, the heat and the colours. The plight of its poor moved me. As a graduate student in the Rhodes Scholar programme at Oxford University in England, I was looking for material to complete a doctorate in philosophy and made a brief visit to New Delhi. There, I spent three to four days during a term break in December.

On a low budget, I travelled by rail. The trains were crowded and the passengers were noisy and boisterous. It was such a contrast to the quiet and subdued cross-country train rides in the United States. I ate whatever my modest budget allowed, and remember enjoying my first taste of idli in southern India. Enveloped by the country’s spirit, I found the whole experience exhilarating.

But I also witnessed the long-term impact of foreign occupation and the devastating effects on its poverty-stricken people. I later saw the same negative impact of long-term foreign intervention in Vietnam. In India, there didn’t seem to be as strong a sense of national pride as I have witnessed in many other countries. At the time, I blamed it on colonialism. But, fifty years later, I also wonder if extreme poverty, corruption and the burden of the old caste system play a large role as well. Of course, the country’s lack of reliable electricity also keeps the population in a type of permanent Dark Ages—pun intended.

Consequently, I was highly encouraged when I learnt that, along with members of the US Congress, President George W. Bush and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had agreed in July 2005 to a nuclear deal to bring electricity to the mass population. The US–India nuclear agreement would allow the United States to supply India with nuclear fuel for civilian power generators. In exchange, India agreed to institute international safeguards on its nuclear reactors to prevent them from being used for military purposes. The negotiations, surprisingly, had been conducted in almost total secrecy. Highly controversial, the agreement ended the United States’ three-decade ban on nuclear trade of any kind with India without requiring the country to join the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) or to dismantle its nuclear weapons programme.

An idealist, especially in the field of international development, might look at this deal as a great victory for the people of India, as the mass population would finally get reliable and clean electricity. In a country where 300 million of its citizens have no electricity and millions more have unreliable electricity, the US–India nuclear agreement—if implemented—could significantly improve the quality of life for more than a billion people.

To development specialists, the US–India nuclear agreement could be a godsend. Nearly 30 per cent of India’s population lives below the poverty line and 75 per cent earns less than 5000 rupees per month. The residents of the state of Bihar are among the most impoverished people in the world, with more than 70 per cent of its population suffering in extreme poverty. An ample and reliable supply of electricity will increase productivity in states like Bihar. More light in homes and in workplaces results in greater activity. This increased productivity will lift up those living in the most abject poverty in India. That is what proponents of the nuclear agreement must state as its main objective. It is a worthy humanitarian goal. But, thus far, the architects of this deal and its advocates have failed to reinforce it.

My love for India and its people is heartfelt. That is why I am so passionate about the transformative effects nuclear power can have on its citizens. If properly implemented, the US–India nuclear agreement could bring electricity, an improvement in the standard of living, and some level of dignity for many poor Indians. The poor are the ones who need the nuclear agreement the most, but so far this deal has just been a shuffling of millions of dollars between governments, arms dealers, consulting firms and lobbyists. Almost a decade after the deal was approved, not one nuclear power plant has even started construction.

Why hasn’t this happened? Importantly absent from the deal was a requirement forcing India to join the NPT and adhere to all its requirements. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, enacted in 1970, extracted a bargain between nuclear weapons states and non-nuclear weapons states. Nuclear weapons states promised to use their nuclear capability only for peaceful purposes in exchange for a promise from non-nuclear weapons states not to pursue nuclear weapons in any form. The US–India nuclear agreement essentially gave India a waiver from the NPT, in an attempt to build a closer relationship with India and counter the rising threat of its powerful neighbour, China. This has antagonized many nuclear non-proliferation advocates, who see this move as a type of ‘nuclear double standard’. Many foreign policy experts claim that the special exemptions the US is giving India have done irreparable damage to global non-proliferation efforts. I tend to agree that we have executed an ‘about face’ on non-proliferation, but I believe it is necessary to get nuclear power for the Indian people.

It took nearly three years for both countries to approve the final agreement, which was signed by the then Indian external affairs minister, Pranab Mukherjee, and his counterpart, the then secretary of state, Condoleezza Rice, on 10 October 2008. Since it is not a treaty and merely an exchange of statements, we must accept the fact that it is not enforceable. Both sides are depending on the goodwill of the other for implementation. The publicly stated purpose of the agreement is to build nuclear plants in India to supply electricity to the country. In actuality, the United States’ primary goal with this deal was, selfishly, an economic one. The US–India nuclear agreement was primarily an arms trade deal. While it certainly was intended to allow nuclear suppliers entry into India, it also opened up vast new trade opportunities between the United States and India for many other industries. So far, the defence industry is the only industry that has enjoyed significant gains from the nuclear deal. This was not a quid pro quo, but the deal did open the doors wide for significantly more arms deals, notably C-130 and C-17 transport aircraft, and joint military exercises with India. This deal is simply a pathway to justify an escalation in arms sales between the two countries. Indeed, Stephen Cohen, a Senior Fellow from the Brookings Institute and an India expert, said that India will be ‘one of the largest markets for defense equipment in the coming two decades’.

President Obama continued the trend started by President Bush and further opened up arms trade between our two countries. In 2009, the Boeing Company won a contract for a $2-billion order for P-3 Orion maritime reconnaissance aircraft. Lockheed Martin secured a $1-billion contract for more C-130 transport aircraft. In 2010, President Obama pledged $5 billion of military equipment to India, making the US one of India’s top three military suppliers. Further efforts were made to loosen antiquated restrictions on technology transfer and to relieve onerous oversight controls. In 2013, the then secretary of defense, Ashton Carter, announced that India would be admitted into the coveted ‘Group of Eight’, the US allies that share the most sensitive technology details—without any export controls.

In 2014, analysts from the military trade publication Jane’s Defense said that India had become the largest foreign buyer of US weapons (only to be outbought by the Saudis in 2015). In 2015, President Obama and Prime Minister Modi announced new partnerships between our countries to jointly develop military jet engine technology and aircraft carrier design. President Obama said publicly that forging deeper ties between our two nations was a primary foreign policy objective for his administration. What he did not say is that these deep ties are mostly military ones. My nation’s new president, Donald Trump, seems poised to build on and reinforce this military relationship and take an even stronger stance against India’s rival, the rogue nation of Pakistan. Indeed, when Prime Minister Modi visited Washington in June of this year, the Trump Administration announced the approval of a $2 billion sale of unarmed drones to India, which raised the hairs on the necks of the Pakistani military and ISI. He also has appointed Lisa Curtis to be the Senior Director for South and Central Asia at the National Security Council. She is a veteran foreign policy expert who has recommended a much more punitive approach to Pakistan. And President Trump has made no apologies for his hard line against Muslim terrorists. Sadly, however, during Prime Minister Modi’s recent visit to Washington, there was no mention of the construction of any nuclear power plants. Their conversation (at least publicly) was strangely silent on this topic.

The US–India nuclear agreement was a good first step towards making India a key global ally. However, the deal has not even begun to achieve its full potential. I fear it never will.

Understanding Tagore’s Nationalism, An Interpretation by Ram Guha — An Excerpt

Rabindranath Tagore was born in 1861. He was the fourteenth child of Debendranath Tagore, head of the Brahmo Samaj. Their family house at Jorasanko was a hive of cultural and intellectual activity and Tagore started writing at an early age. He was a prolific writer; his works include poems, novels, plays, short stories, essays and songs. Late in his life Tagore also took up painting, exhibiting in Moscow, Berlin, Paris, London and New York. He died in 1941.

Born in Dehradun in 1958, and educated in Delhi and Calcutta, Ramachandra Guha pursued an academic career for ten years before becoming a full-time writer. He was named one of the hundred most influential intellectuals in the world by Foreign Policy and Prospect magazines.

Here’s an excerpt from the introduction of Tagore’s Nationalism written by Ram Guha.

‘Why Tagore?’ asked a brilliant young mathematician of me recently. He was referring to a newspaper column where I had spoken of Rabindranath Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi,

Jawaharlal Nehru and B.R. Ambedkar as the ‘four founders’ of modern India. ‘I can see why you singled out the other three,’ said the mathematician. ‘Gandhi led the freedom movement, Nehru nurtured the infant Indian state, Ambedkar helped write its Constitution and gave dignity to the oppressed.

But why Tagore?’ My questioner was no ordinary Indian. He comes from a family of distinguished scholars and social reformers. Like his father and grandfather before him, he had been educated at a great Western university but came back to work in India. Like them, he is well read and widely travelled, and yet deeply attached to his homeland. He fluently speaks three Indian languages. If an Indian of his sensibility had to be convinced of Tagore’s greatness (or relevance), what then of all the others?

Tagore’s reputation, within India and outside it, has suffered from his being made a parochial possession of one province, Bengal. It was in Bengali that he wrote his poems, novels, plays and songs, works that are widely read and regularly performed seven decades after his death. The poet Subhas Mukhopadhyay recalls ‘a time when the elite of Bengal fought among themselves to monopolise Tagore. They tried to seal off Tagore, cordoning him away from the [sic] hoipolloi.’ Then he adds: ‘There was another trend, serving the same purpose, but in a different way. In the name of ideology and as the sole representative of the masses, some tried to protect the proletariat from the bourgeois poet’s harmful influence!

The Bengali communists have since taken back their hostility to Tagore—now, they quote his verses and sing his lyrics with as much gusto as their (bourgeois) compatriots.

But he remains the property of his native heath alone. This geographical diminution of the man and his reputation has been commented upon by that other great world traveller and world citizen of Bengali extraction, the sitar player Ravi Shankar. In his autobiography, the musician writes that ‘being Bengali, of course, makes it natural for me to feel so moved by Tagore; but I do feel that if he had been born in the West he would now be [as] revered as Shakespeare and Goethe . . .

He is not as popular or well-known worldwide as he should be. The Vishwa Bharati are guarding everything he did too jealously, and not doing enough to let the entire world know of his greatness.’

Ravi Shankar compared Tagore to the German genius Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 1832); so, before him, had the critic Buddhadeva Bose. Both men, remarked Bose, ‘participate[d] in almost everything’.Certainly, no one since Goethe worked in so many different fields and did original things in so many of them. Tagore was a poet, a novelist, a playwright, a lyricist, a composer and an artist. He had good days and bad, but at his best he was outstanding in each of these fields.

Tagore’s poems and stories are mostly set in Bengal. However, in his non-fiction, that is to say in his letters, essays, talks and polemics, he wrote extensively on the relations between the different cultures and countries of the world. Tagore, notes Humayun Kabir, ‘was the first great Indian in recent times who went out on a cultural mission for restoring contacts and establishing friendships with peoples of other countries without any immediate or specific educational, economic, political or religious aim. It is also remarkable that his cultural journeys were not confined to the western world’. He visited Europe and North America, but also Japan, China, Iran, Latin America and Indo-China.

Read the complete introduction by Ramachandra Guha in the new edition of Rabindranath Tagore’s Nationalism. Get your copy here.

When the Journey Began: ‘India at 70’ — An Excerpt

In 2017, India’s spacecraft Mangalyaan is orbiting Mars, satellites are regularly sent into space, the economy is growing rapidly and India’s diverse art and culture is appreciated globally. And, most importantly, India is the largest democracy in the world.

The story of India as an independent nation began seventy years ago, in 1947, when the country gained independence after almost 200 years of British rule. For the first time, India became a united political entity, a nation with clearly defined boundaries. What type of country would the new India be? Would it remain united and strong?

At this time, the territory known as India consisted of eleven British provinces and some additional areas directly under British rule as well as 565 Indian states (also called princely states) where the British had overall control. The Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, wanted a separate state of Pakistan, and finally it was decided that this demand would be granted. On 14 and 15 August 1947, two new nations were created, but the boundary lines between them were known only on 17 August. Pakistan was in two parts; West Pakistan was formed in the western half of Punjab while East Pakistan was created from the province of Bengal. As the lines for dividing the area were drawn on a map, districts, canals and even villages were divided.

This partition of one country into two created many problems. In the west, 10 million migrated across the new borders, and as anger arose between Muslims on one side and Hindus and Sikhs on the other, about 1 million were killed. There were other issues too, as the entire administration and all its possessions—including tables, chairs, books, musical instruments, cars, pencils and pens as well as the army, police, railways, postal services, money and other items—had to be divided.

The process of integrating the different states to form one India began before Independence. While some of the states were in the region of Pakistan, 554 states were in Indian territory. These states had different kinds of rulers. Some controlled huge areas and had vast quantities of wealth, land, buildings, money, gold, jewels, cars and elephants; others had small territories of just a few square kilometres. There were actually 425 small states. By 31 July, two types of agreements had been worked out for the Indian states to sign, by which they agreed to join India and give up some of their powers. At the time of Independence, the Constitution of India was being prepared. A constitution consists of the rules and ideas according to which a nation is governed. The Constituent Assembly, a group of people who would discuss and write India’s constitution, first met on 9 December 1946. The Constitution was ready by the end of 1949, after which India became a republic in 1950. Two years later, the first elections were held and India’s Parliament began to function. Thus, though India’s complex history dates back to the Stone Age, the year 1947 brought in great change.

This is an excerpt from the introductory chapter of Roshen Dalal’s ‘India at 70’. Get your copy here today!

25 Must Reads On the 70th Anniversary of Partition

India’s freedom from the British rule was stained by the horrors of its partition. The reverberations of the event over the last seventy years have been encapsulated in several books, plays, and other forms of media.

Here is a list of 25 books that capture one of the most defining moment of our history.

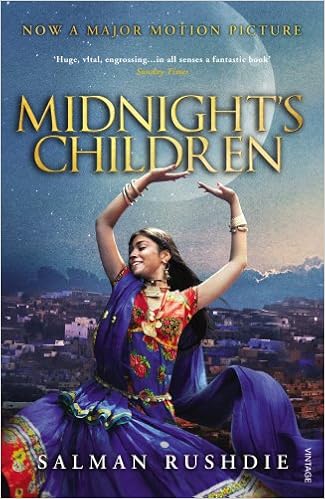

Midnight’s Children

Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie is an epic novel that opens up with a child being born at midnight on 15th August 1947, just at a time when India is achieving Independence from centuries of foreign British colonial rule. Highlighting the relation between father and son and a nation yet in its nascent stage, it is an enchanting family adventure with lots of human drama and shocking summoning.

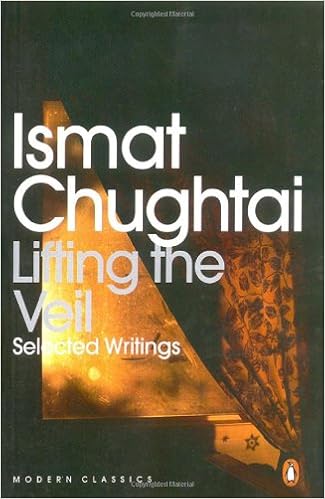

Lifting The Veil

Ismat Chughtai in Lifting the Veil explored female sexuality with unparalleled frankness and examined the political and social mores of her time.

Train to India: Memories of Another Bengal

As a young boy, Maloy Krishna Dhar, made the perilous journey to India from the East Pakistan. The partion in Bengal had its share of tragedy, of lives unmade and lost, but it is relatively less chronicled than events in Punjab. Maloy Krishna Dhar’s Train to India is a graphic and moving account of that turbulent and unforgotten era of Bengal History.

The Shadow Lines

As a young boy, Amitav Ghosh’s narrator in The Shadow Lines travels across time through the tales of those around him, traversing the unreliable planes of memory, unmindful of physical, political and chronological borders. Bits and pieces of stories, both half-remembered and imagined, come together in his mind until he arrives at an intricate, interconnected picture of the world where borders and boundaries mean nothing, mere shadow lines that we draw dividing people and nations.

Midnight’s Furies

Nisid Hajari’s Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition shows how Partition, which has created such a wide gulf between two countries whose people have so much in common, has given birth to global terrorism and dangerous proliferation.

On a backdrop India’s struggle for independence, Laila, an orphaned daughter of a distinguished Muslim family, fights for her own independence from the claustrophobia of a traditional life. With its beautiful evocation of India, its political insight and unsentimental understanding of the human heart, Sunlight on a Broken Column, first published in 1961, is a classic of Muslim life.

With India’s partition in 1947 as its reference point, the novel presents a limitless canvas against which the most extraordinary trial in the history of mankind runs its course. Kamleshwar’s Kitne Pakistan dared to ask crucial questions about the making and writing of history.

Amritsar to Lahore by Stephen Alter

A sensitive and thoughtful look at the lasting effects of Partition on everyday people, Amritsar to Lahore describes a journey across the contested border between India and Pakistan in 1997, the fiftieth anniversary of Partition. Offering both the perspective of hindsight and a troubling vision of the future, Amritsar to Lahore presents a compelling argument against the impenetrability of boundaries and the tragic legacy of lands divided.

The Broken Mirror by Krishna Baldev Vaid tells the story of Beero and his group of friends against a backdrop of partition of India. Beero’s passage through adolescence is told through a series of eccentric characters. When partition becomes a reality, in a time of terror and carnage, the insane turn out be the only ones sane.

If Partition affected the lives of Sindhi Hindus, it also changed things for the Sindhi Muslims. In Unbordered Memories, Sindhis from India and Pakistan make imaginative entries into each other’s worlds. Many stories in this volume testify to the Sindhi Muslims’ empathy for the world inhabited by the Hindus, and the Indian Sindhis’ solidarity with the turbulence experienced by Pakistani Sindhis.

The Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 left a legacy of hostility and bitterness that has bedevilled relations between India and Pakistan. Reviewing the turbulent history of their past relationship, Radha Kumar analyses the chief obstacles the two countries face in the light of the new opportunities and challenges that the twenty-first century presents.

Bitter Fruit: The Very Best of Saadat Hasan Manto

Manto’s stories were mostly written against the backdrop of the Partition. Bitter Fruit presents the best collection of Manto’s writings, from his short stories, plays and sketches, to portraits of cinema artists, a few pieces on himself. Bitter Fruit includes stories like A Wet Afternoon, The Return, A Believer s Version, Toba Tek Singh, Colder than Ice and many others.

Kingdom’s End: Selected Stories

This collection brings together some of Manto’s finest stories, ranging from his chilling recounting of the horrors of Partition to his portrayal of the underworld. Powerful and deeply moving, these stories remain as relevant today as they were first published.

Mottled Dawn by Saadat Hasan Manto is a collection of stories based on the India-Pakistan partition. The stories written around 1947 put forward the most tragic events in the history of the subcontinent.

Saadat Hasan Manto’s stories are vivid, dangerous and troubling and they slice into the everyday world to reveal its sombre, dark heart. These stories were written from the mid-1930s on, many under the shadow of Partition. No Indian writer since has quite managed to capture the underbelly of Indian life with as much sympathy and colour.

Written by the first President of India, India Divided traces the origins and growth of the Hindu–Muslim conflict, gives the summary of the several schemes for the partition of India which were put forth, and points out the essential ambiguity of the Lahore Resolution. Finally, it concludes that the solution for the Hindu–Muslim issue should be sought in the formation of a secular state, with cultural autonomy for the different groups that make up the nation.

Mr and Mrs Jinnah: The Marriage That Shook India Sheela Reddy in Mr and Mrs Jinnah brings forth the marriage that convulsed the Indian society with a sympathetic, discerning eye. A product of intensive and meticulous research in Delhi, Bombay and Karachi, and based on first-person accounts and sources, Reddy sheds light on how the politics of the time affected the marital life of misunderstood Jinnah and wistful Ruttie.

Sheela Reddy in Mr and Mrs Jinnah brings forth the marriage that convulsed the Indian society with a sympathetic, discerning eye. A product of intensive and meticulous research in Delhi, Bombay and Karachi, and based on first-person accounts and sources, Reddy sheds light on how the politics of the time affected the marital life of misunderstood Jinnah and wistful Ruttie.

A timeless classic about the Partition of India, Tamas is also a chilling reminder of the consequences of religious intolerance and communal prejudice.

Bengal Divided: The Unmaking of a Nation (1905-1971)

In 1905, all of Bengal rose in uproar because the British had partitioned the state. Yet in 1947, the same people insisted on a partition along communal lines. Exploring the roots of alienation of the two communities, Nitish Sengupta peels off the layers of events in this pivotal period in Bengal’s history, casting new light on the roles of figures such as Chittaranjan Das, Subhas Chandra Bose, Nazrul Islam, Fazlul Huq, H.S. Suhrawardy and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee.

In Mukul Kesavan’s Looking Through Glass, a young photographer on a train to Lucknow suddenly finds himself in the deep end of 1942. His hindsight tells him that Partition will destroy this world. And in his desperate struggles to avert the inevitable, we discover, often with an almost unbearable poignancy, how the possibilities in India’s past were squandered, some wantonly, others accidentally.

A collection of two novellas—Regret and Out of Sight, the stories skilfully evoke the long shadow cast by the violence of Partition. While Regret brilliantly recreates a childhood shattered by the Partition of India in 1947, Out of Sight recounts the story of Ismail, who narrowly escaped the carnage of 1947 in his youth. Now, looking back on his life and despairing of the sudden resurgence of sectarian violence in Pakistan.

Memories Of Madness: Stories Of 1947

The tragic legacy of Partition haunts the subcontinent even today. Memories of Madness brings together works by three leading writers who witnessed the insanity of those months—Khushwant Singh, Saadat Hasan Manto, and Bhisham Sahni. As moving as they are disturbing, the stories in this volume are of immense relevance in these times, for they constitute a chilling reminder of the consequences of communal politics.

The Other Side of Silence

Pieced together from oral narratives and testimonies, in many cases from women, children and dalits— marginal voices never heard before— and supplemented by documents, reports, diaries, memoirs and parliamentary records, this is a moving, personal chronicle of Partition that places people, instead of grand politics, at the centre.

The dark legacies of partition have cast a long shadow on the lives of people of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The borders that were drawn in 1947, and redrawn in 1971, divided not only nations and histories but also families and friends. The essays in this volume explore new ground in Partition research, looking into areas such as art, literature, migration, and notions of ‘foreignness’ and ‘belonging’.

Remembering Partition: Limited Edition

The Remembering Partition Box Set is a collection of five iconic books which look at the different faces of partition, from the larger political and historical view to the very personal tales of hatred, grief, courage and friendship.

On the 70th anniversary of partition, which book are you picking?

The Making of Pressler Amendment— An Excerpt

As chairman of the US Senate’s Arms Control Subcommittee, Larry Pressler advocated the now-famous Pressler Amendment, enforced in 1990 when President George H.W. Bush could not certify that Pakistan was not developing a nuclear weapon. Larry Pressler was adjudged a hero in India and a ‘devil’ in Pakistan due to his stance on giving military aid to Pakistan. In his book ‘Neighbours in Arms’ Pressler provides a comprehensive account of how US foreign policy in the subcontinent was formed from 1974 till today and ends with recommendations of a new US-India alliance that could be a model for American allies in future.

Here’s an exclusive excerpt from the book.

In December 1981, a new section was added to the 1961 Foreign Assistance Act. It allowed the President to exempt Pakistan from the original Symington Amendment ‘if he determines that to do so is in the national interest of the United States’. (It is important to note that Pakistan was the only nation specifically exempted by name from these restrictions.) Almost immediately, Congress also authorized a six-year $3.2-billion package of military and economic assistance to Pakistan. I was opposed to this move, as I knew it would further encourage Pakistan to continue the development of their nuclear weapons programme.

Many of us in Congress knew that we could not trust President Zia to be honest with us about his nuclear ambitions. Everyone knew that Pakistan was continuing to acquire material and technology

to develop a bomb. Despite this fact, the Reagan administration wanted a new law that would give him a permanent waiver from the Glenn–Symington Amendment. At the time, guaranteeing Pakistan’s assistance in the fight against the Soviets in Afghanistan was more important than stopping Pakistan’s acquisition of nuclear weapons technology. The only way the administration could get Congress to go along with this permanent waiver was to include language in a new law that would punish Pakistan if it was determined that Pakistan actually possessed a nuclear weapon. This made the Glenn–Symington waiver more politically feasible to those of us in Congress who were working hard on non-proliferation issues. I was tapped to carry the ball and the Pressler Amendment was born.

My goal was to give this new amendment as much ‘teeth’ as possible. On 24 March 1984, the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations introduced an amendment offered up by California Democratic senator Alan Cranston and Senator Glenn. This first amendment stipulated that ‘no military equipment or technology shall be sold or transferred to Pakistan’ unless the President could

first certify that Pakistan did not possess nor was developing a nuclear explosive device, and that it was not acquiring products to make a nuclear explosive device. On 18 April 1984, the committee instead introduced a substitute offered by me, Maryland Republican senator Charles Mathias and Senator Charles Percy.

My former staff member, the late Dr Doug Miller, recalled that Senator Cranston’s face appeared ‘crestfallen’ when his amendment did not pass. In retrospect, while Cranston’s amendment and my

subsequent amendment were very similar, I feel his amendment would have cut off aid to Pakistan sooner. But the Republican Party was in control at the time. They wanted a Republican name on the

amendment.

The revised amendment offered by Senators Mathias, Percy and me instead tightly tied the continuation of aid and military sales to two presidential certification conditions: (1) that Pakistan did not possess a nuclear explosive device; and (2) that new aid ‘will reduce significantly the risk’ that Pakistan would possess such a device. This text was further revised with a provision offered by me, Senator Mathias and Minnesota Republican senator Rudy Boschwitz that the ‘proposed U.S. assistance [to Pakistan] will reduce significantly the risk of Pakistan possessing such a [nuclear] device’. It forced the President to affirm that increased aid was reducing the risk of Pakistan

getting nuclear weapons. I thought at the time that this was going to be impossible for any President to certify—based on Pakistan’s past behaviour and what President Reagan had assured me he would do.

The final text of Section 620E of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 read:

No assistance shall be furnished to Pakistan and no military equipment or technology shall be sold or transferred to Pakistan, pursuant to the authorities contained in this Act or any other Act,

unless the President shall have certified in writing to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations of the Senate, during the fiscal year in which assistance is to be furnished or military equipment or technology is to be sold or transferred, that Pakistan does not possess a nuclear explosive device and that the proposed United States assistance program will reduce significantly the risk that Pakistan will possess a nuclear explosive device.

This text, which was signed into law by President Reagan on 8 August 1985, soon became known as the ‘Pressler Amendment’, even though I was not the only sponsor. I never referred to it as the Pressler Amendment. But when President George H.W. Bush later enforced it, the Pentagon wrote a series of worldwide memos and briefings explaining that Bush had to act in such a way towards Pakistan because of ‘Senator Pressler’s amendment’, mentioning me by name and making the amendment eponymous. It is important to understand that this legislation was passed at the request of and with the support of the Reagan administration. That is why I was so astounded when later Reagan never enforced it.

In summary, it made a law out of what had already been an official policy: our conventional arms assistance and financial aid to Pakistan would reduce the risk of nuclear proliferation. It used the power of the purse. It allowed us to pursue our communism-containment goals in the region, but it was also intended to force our leaders to proactively assert—on the record—that Pakistan was not making progress on its nuclear goals. Again, this policy seems counter-intuitive and, unfortunately, it had the opposite effect on Pakistan. And, with the help of the Octopus, Pakistan took our aid and flagrantly ignored the Pressler Amendment restrictions.

What’s Ailing Our Legal System: 5 Big Challenges

India has the second-largest legal profession in the world, but the systemic delays and chronic impediments of its judicial system inspire little confidence in the common person. In India’s Legal System, renowned constitutional expert and senior Supreme Court lawyer Fali S. Nariman looks for possible reasons.

This frank and thought-provoking book offers valuable insights into India’s judicial system and maps a possible road ahead to make justice available to all. Here are the five challenges that the book underscores.

Proliferation of Appeals

Judicial Interference in Administrative Actions

Judicial Attitudes

Excessive burden of case law, and lack of effective case law management

Overcommercialization

In your opinion, what is the gravest challenge facing the Indian Legal System? We would love to know!

The Ups and Downs of Narendra Modi’s Governance

Uday Mahurkar in his latest book Marching with a Billion takes stock of Narendra Modi’s three years in power. Focusing on key areas of governance like infrastructure, foreign affairs, finance, digital technology, etc. Mahurkar showcases the work of the present government and the monumental changes the prime minister has brought about.

Here are ten highlights of Narendra Modi’s tenure:

Nearly 27 crore poor people opened their bank accounts under Narendra Modi’s Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana.

Uday Mahurkar points out that India has emerged as the number one global destination for FDI because of these two factors.

There have been disputes going on between investors and shipping ministry on account of the retrospective regulations slapped by the A.B. Vajpayee government fifteen years ago.

Uday Mahurkar notes that the relationship Modi is forging with the US, cutting across that country’s web of diplomatic calculations, is also new in the history of India’s diplomacy. The way Modi capitalized on India’s strength during his June 2016 US visit, which took the US Congress by storm and instilled the fear of isolation in the heart of Pakistan, and even China, left the world powers impressed.

Modi’s government is probably the first since Independence that has made a real attempt to involve the people in the process and, that too, quite successfully.

Modi, who has always been ahead of his times in adopting the latest technology, told the officials that he wanted to link people to digital technology like nowhere else in the world.

One big criticism of the government on reforms is what many people call its failure to disinvest big PSUs like Air India, SAIL and CIL. There is a view that taxation and banking reforms could have been faster. Mahurkar quotes a senior BJP leader with sound knowledge of the Indian economy who says: ‘What was needed was a transformational approach on reforms, but many steps indicate the government’s approach has been selectively incremental.’

Mahurkar observes that Modi’s China diplomacy signals a great change in India’s attitude towards that nation—from a defensive posture maintained over several decades to that of equal, controlled aggression. Modi gave another sign of India’s new stance soon after the G20 summit in the way he chose to react to the China–Philippines dispute in the South China Sea at the summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations at Laos.

According to Uday Mahurkar, the prime minister believes that the country has to overcome the urban–rural digital divide if it is to move forward.

Uday Mahurkar points out that there have been projects under Nitin Gadkari, Minister of Road Transport and Highways of India in Modi government, which have not taken-off yet.

Tell us what you think of Narendra Modi’s governance in the past three years.

Five significant contributions of Islam’s advent in India

The relationship between Hindu and Islamic traditions has existed in the subcontinent since the Persians set foot in Asia. The relationship has seen a lot turns and turmoil ever since. In the light of recent political climate, the alliance has become more relevant.

Historian Raziuddin Aquil, in his book The Muslim Question: Understanding Islam and Indian History has given a poignant and detailed account of the evolution of Islam from its prime to its transformation in India due to colonialism.

Here are five instances which capture the legacy of Islam in India.

India’s integration of Islam also opened a transfer of fresh political ideas which had evolved over the centuries in Iran and Greece. In many ways, this was a re-emergence of political ideas in a new garb.

There was also an emergence of ‘syncretic’ traditions in different regions which did not conform to any particular religion.

Although the main undertaking of Sufi traditions was to restrict any deviations from the Muslim rule, their belief in unity within multiplicity contributed to religious synthesis and cultural amalgamation.

Jalal-ud-Din Muhammad Akbar due to his inclusive religious and administrative policies is regarded as one of the greatest rulers of India.

Under Akbar’s rule, man’s reason (aql), not tradition (naql), was acknowledged as the only basis of religion.

Read more about Islam’s journey in Raziuddin Aquil, in his book The Muslim Question: Understanding Islam and Indian History. Get your copy here.