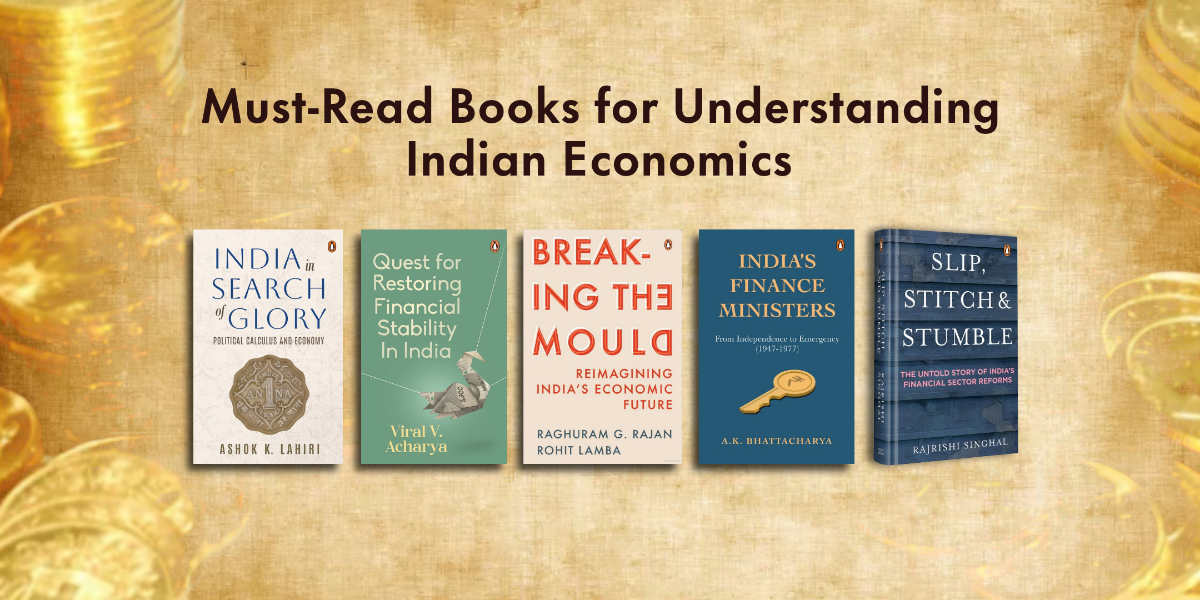

As the 2024 elections continue, understanding Indian Economics and its issues is key for informed voting. With a complex landscape shaped by rapid growth, persistent challenges, and reforms, Indian Economics is at a pivotal juncture. Understanding its intricacies can empower voters to make decisions as India stands on the brink of significant change. Dive into these seven must-read books, packed with insights to help you make sense of it all and vote wisely for a brighter future.

India and the Indians have made some progress in 75 years after Independence. The number of literates has gone up. The Indians have become healthier and their life expectancy at birth has gone up. The proportion of people below the poverty line has also halved. But the shine from the story fades when India is compared with that of the East Asian Tigers and China. It looks good but not good enough. India looks far away from the glory it seeks. This issue forms the core subject matter of this book. It tries to argue why India could not achieve more and what all it could have achieved. It paints a picture of its possible future and highlights the areas that need immediate attention.

How to maintain financial stability in India? Quest for Restoring Financial Stability in India is a classic work to understand this critical subject. In this Penguin edition, with a new introduction, Viral V. Acharya, former Deputy Governor of RBI offers a concrete road map for comprehensive improvement of India’s economy. Authoritative and definitive, this is a must read for the students and scholars of Indian economy, policymakers and anyone interested in India’s finance sector.

India is at a crossroads today. Its growth rate, while respectable relative to other large countries, is too low for the jobs our youth need. Intense competition in low-skilled manufacturing, increasing protectionism globally and growing automation make the situation still more difficult. Divisive majoritarianism does not help. India

broke away from the standard development path—from agriculture to low-skilled manufacturing, then high-skilled manufacturing and, finally, services—a long time back by leapfrogging the intermediate steps. Rather than attempting to revert to development paths that may not be feasible any more, we must embark on a truly Indian path.

In Breaking the Mould, the authors explain how we can accelerate economic development by investing in our people’s human capital, expanding opportunities in high-skilled services and manufacturing centred on innovative new products, and making India a ferment of ideas and creativity. India’s democratic traditions will support this path, helped further by governance reforms, including strengthening our democratic institutions and greater decentralization.

Manmohan Singh’s 1991 Union Budget speech made history by altering the course of the Indian

economy, especially its financial sector. His measures took a broom to multiple cobwebs in this sector. What Manmohan Singh started over three decades ago is still a work in progress today, but it does raise some questions: Why did he focus on financial sector reforms? What has motivated continuing these reforms?

This book tries to answer questions like these while focusing on the evolution of financial sector reforms which, oddly, remain incomplete even after thirty years. The fabric of this sector has been fraying and initiatives over the past three decades have resembled hasty, temporary needlework; the patchwork, incomplete reforms make the sector further vulnerable to failure. Hence: Slip, Stitch and Stumble.

India’s Finance Ministers: Stumbling into Reforms (From 1977 to 1998) is the second volume in the series of books on some of India’s unforgettable finance ministers. Analysing the role of India’s finance ministers who managed India’s economy during one of its worst phases (post Emergency to the late 1990s), the book highlights the lasting impact they left on India’s political economy. This volume also provides a fascinating account of India’s economic history offering an incisive view of the key events in India’s journey from an closed, agrarian economy to a liberal economy.

A general perception exists that ancient Indian literature on economic matters is fatalistic and an admixture of sacred and secular thoughts. Economic Sutra provides a comprehensive perspective on the elements of Indian economic thought leading up to and after the Arthashastra. Economic Sutra is a perception-correction initiative to distil the Indian mind in the realm of economic thoughts and behaviour as brought out by the ancient Indian authors. It highlights the broader spread of economic ideas both prior to and sometime after Kautilya, giving insights into the purpose, actions and vision of our forefathers.

Imagine you have a few million dollars. You want to spend it on the poor. How do you go about it? Billions of government dollars, and thousands of charitable organizations and NGOs, are dedicated to helping the world’s poor. But much of their work is based on assumptions about the poor and the world that are untested generalizations at best, harmful misperceptions at worst.

Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo have pioneered the use of randomized control trials in development economics through their award-winning Poverty Action Lab. They argue that by using randomized control trials, and more generally, by paying careful attention to the evidence, it is possible to make accurate-and often startling assessments-on what really impacts the poor and what doesn’t.

Over the past decade, that ‘emerging middle’ has risen further, consisting of 800 million Indians and shaping countries like India into a Diamond.

Over the past decade, that ‘emerging middle’ has risen further, consisting of 800 million Indians and shaping countries like India into a Diamond.