The evening prayers in the ashram are over. Cowbells tinkle sweetly in the distance. The residents of the ashram sit in a circle, their eyes fixed on Shyam, who has promised them a story as sweet as lemon syrup. And so Shyam begins.

While on some evenings he tells them of his boyhood days, surrounded by the abundant beauty of the Konkan, on others he recalls growing up poor, embarrassed by the state of his family’s affairs. But at the heart of each story is his Aai-her words and lessons.

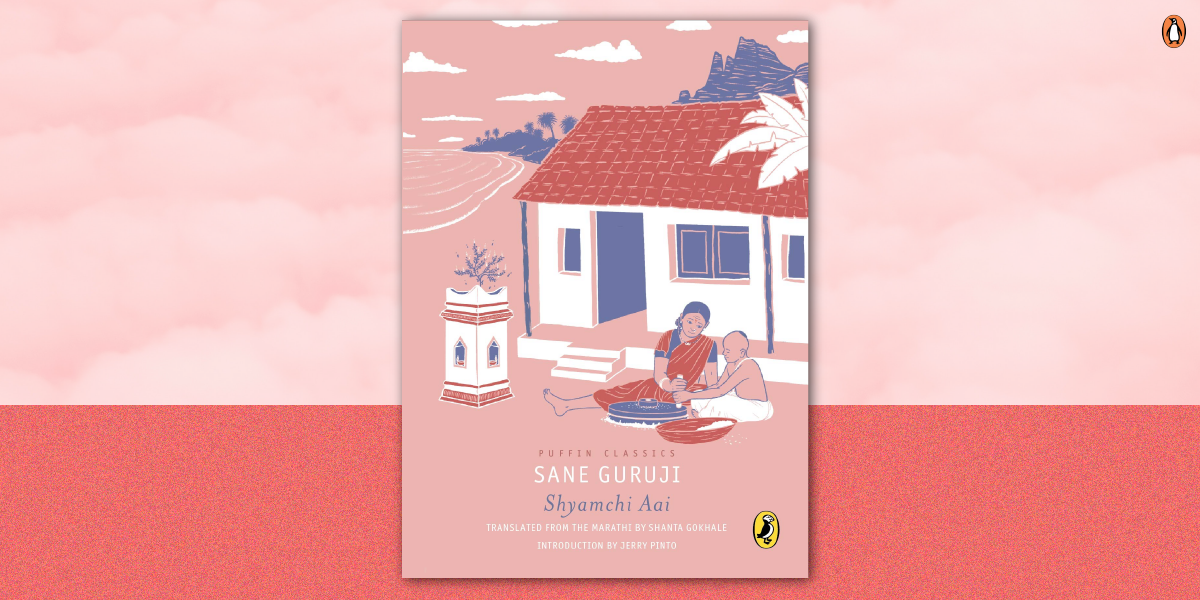

Narrated over the course of forty-two nights, Shyamchi Aai is a poignant story of Shyam and Aai, a mother with an unbreakable spirit. Here, we are sharing an excerpt from the book where Shyam reflects on the relationship between his parents and how they had both taught him important life-lessons.

**

It was Bhau’s custom to go to the temple after he finished his puja at home. That was the signal for us to lay the plates for lunch. We would serve everything else before he came back except for the rice. When we saw him coming, we would call out, ‘Bhau’s here, Aai. Bhau’s here. Serve the rice.’ Bhau would bring back holy water from the temple. We would have that and then settle down to lunch.

That day, Aai had made a dish from sweet potato greens. She used to make tasty dishes from the leaves of all kinds of vegetables like pumpkins and ladies’ fingers. She would say, ‘Anything can be made to taste good if it’s tempered with a couple of spices and the right amount of salt and chilli powder are added.’ She was right, of course, because whatever she made did indeed taste good. The culinary deity seemed to dwell in her fingers. She would pour her heart and soul into everything she made.

However, that day was a little different. There was no salt in the vegetable dish she had made. With all the work she had to do, she had simply forgotten to put it in. Bhau didn’t mention it, so we didn’t either. Bhau’s self-control was unbelievable. Every time Aai offered him another helping of the vegetable, he would say, ‘This is excellent.’ He neither added the salt that was served on his plate nor asked for any. Aai said to me, ‘Don’t you like the dish? You’re not eating it the way you normally do.’ Before I could answer, Bhau cut in with, ‘Now that he has started learning English at school, he’s not going to enjoy these rustic vegetables.’

‘Not at all,’ I protested. ‘If learning English is going to do that to me, I don’t want to learn it. Please don’t send me to school.’

Bhau said, ‘I said that only to make you angry. When you get angry, I know all is well with the world. You like jackfruit, don’t you? I’ll get one tomorrow from Patil Wadi. If I don’t find a tender one, you can have the pods boiled and spiced.’

Aai said, ‘Yes, please get one. We haven’t had jackfruit in a long time.’ Bhau went out to the verandah for his routine walk and prayers. After that he spun yarn for his sacred thread. The spinning disc was made of clay. The house rule was that all of us should know how to spin yarn.

Aai had finished clearing up and had now sat down for her lunch. I was sitting nearby. She took her first mouthful of the vegetable and discovered it had no salt. ‘Shyam, there’s no salt in this dish. None of you said so. Why didn’t you tell me? How could you eat this saltless dish?’

‘We said nothing because Bhau said nothing,’ I replied. Aai was very upset.

‘How did you eat this?’ she kept asking. ‘No wonder you didn’t have much. Otherwise you would have single-handedly finished half the lot. You like your vegetables. I should have known then. But what’s the use of saying it now?’

Aai was full of remorse for her mistake. She believed we should always give people the best we can, whatever it is. She felt she had been careless, not paid enough attention, lost her concentration on the job. She had done wrong and she refused to forgive herself.

Bhau had said nothing because he hadn’t wanted to upset her. She had spent so much time at the hearth breathing in all the smoke and fumes just to make food for us. Why find fault? Why not accept what was made as tasty? Bhau believed it was wrong to hurt the person who had cooked for you.

‘Friends, it is for us to decide who the finer human being was. Was my father the finer human being because he ate an unsalted dish as if it were the best he had ever eaten in the belief that it was better to control one’s tongue than hurt another’s feelings? Or was my mother the finer human being because she was upset over serving us something that wasn’t perfect, asked us why we hadn’t complained and wouldn’t forgive herself for her mistake? According to me, both were fine human beings.

Our culture is founded on self-control and contentment as well as on doing work as perfectly as possible. I learnt from my parents that we should aspire to both these virtues in life.’

**