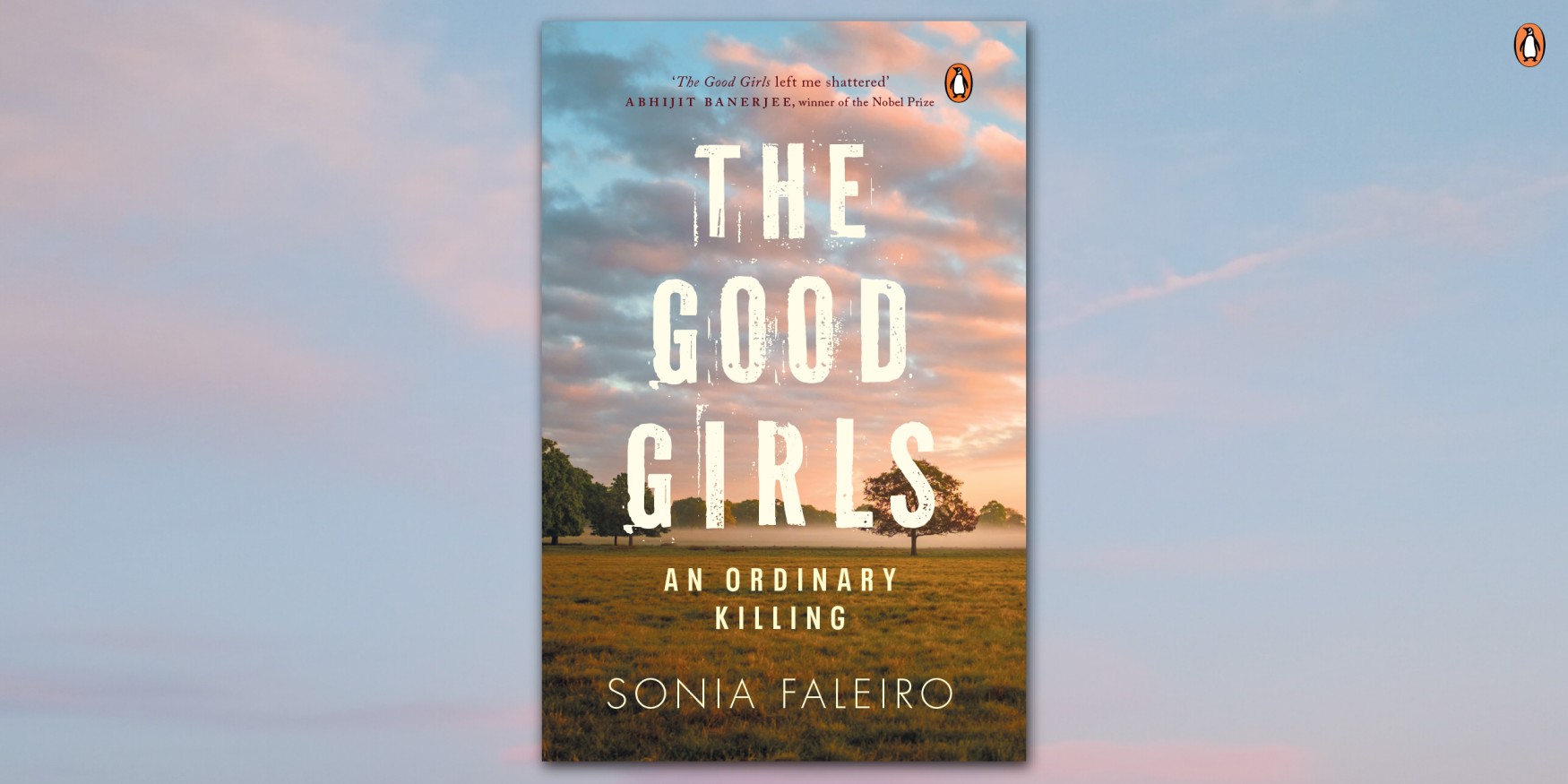

In the early dawn one day in 2014, a man discovered the dead bodies of 14-year-old Lalli Shakya and 16-year-old Padma Shakya hanging from a mango tree on the edge of their village in Uttar Pradesh. Upon hearing of the discovery and reaching the bodies, the grief-stricken women of the family formed a protective shield around the tree. They knew that if their girls were taken down immediately, they would be forgotten, lost in a brutally inefficient and prejudiced system; but if media arrived, and photos of the bodies went viral, those in power could not ignore the deaths and justice would be served.

A shattering, utterly immersive work of investigative journalism, based on years of meticulous reportage The Good Girls slips behind political maneuvering, caste systems and codes of honour in a village in northern India to uncover the real story behind the tragic deaths of two teenage girls and an epidemic of violence against women. Read on for a glimpse into the devastating fault lines created by caste, gender, technology and revealed by a tragedy that shook the imagination and hopefully the conscience of a nation.

In the year that Padma and Lalli went missing, 12,361 people were kidnapped and abducted in Uttar Pradesh, accounting for 16 per cent of all such crimes in India. Across the country, one child went missing every eight minutes, said Kailash Satyarthi, who went on to jointly win the Nobel Peace Prize with Malala Yousafzai. And these were just the reported cases. The economist Abhijit Banerjee, who later also jointly won a Nobel Prize for his approach to alleviating global poverty, explained that ‘parents may be reluctant to report children who ran away as a result of abuse, sexual and otherwise.’ He added that this was likely ‘rampant’. In fact, some parents sold their children or deliberately allowed unwanted daughters to stray in busy marketplaces. No one reported them missing, and so, no one looked for them. Even in a tiny village like Katra where everyone was of the same social class, the Shakya family believed that the police would still take sides. They would choose to favour the person of their caste. And told that the culprit was Yadav, they would most likely wave away the Shakyas, being Yadavs themselves. ‘Raat gayi toh baat gayi,’ they would say, grunting back to sleep. The night has concluded and so has the incident. ‘It was easy to ask why we didn’t immediately go to the chowki,’ Jeevan Lal would later complain. Time was scarce and he preferred not to waste it on a thankless task. There was, however, another reason that Padma’s father held back. By 10.15 p.m., a dozen men were searching for Padma and Lalli in the Shakya family plots. Some in the group assumed that the girls were injured and unable to call for help. Around the search party, termites crawled, mosquitoes buzzed and moths fluttered. As the heat drained out, the field rustled with snakes slipping back into their holes. Nazru excused himself – to eat dinner, he said. The others waded through the upturned earth of Jeevan Lal’s property. They tramped into the orchard. They arrived at the dagger-leafed eucalyptus grove. They went as far as the tube well that adjoined the Yadav hamlet. They moved quickly and, at the request of Padma’s father, they didn’t call out the girls’ names. They were as quiet as they could be. A villager who lived some 400 feet from the Shakya plots had gone into the fields to empty his bladder several times that night, but when questioned about it later he said he didn’t hear or see anything. Certainly, there was nothing to suggest that a group of men armed with torches and tall, heavy sticks were in search of missing children. Jeevan Lal didn’t need to spell out what was at stake, but he did anyway: ‘Our daughters are unmarried,’ he said. ‘Why would we ruin their chances of finding a good match?’ The other villagers would have asked why the girls had been allowed out at night with a phone, and without a chaperone. ‘There’s no point crying after the birds have eaten the harvest,’ they would have said. But the girls had been taken by Pappu. Nazru had said so – and Jeevan Lal knew this, even if the others didn’t. ‘This is the sort of place where people cause a commotion over a missing goat,’ a village storekeeper later said. ‘If the girls were taken by Pappu, as Nazru said, why didn’t the family make any noise or call out to anyone?’ They didn’t, because it wasn’t just the girls’ honour that was at stake, it was the family’s too. And the family had to live in the village. And so, just like that, in less than an hour since they were gone, Padma was no longer the quick-tempered one. Lalli was no longer the faithful partner in crime. Who they were, and what had happened to them, was already less important than what their disappearance meant to the status of the people left behind.