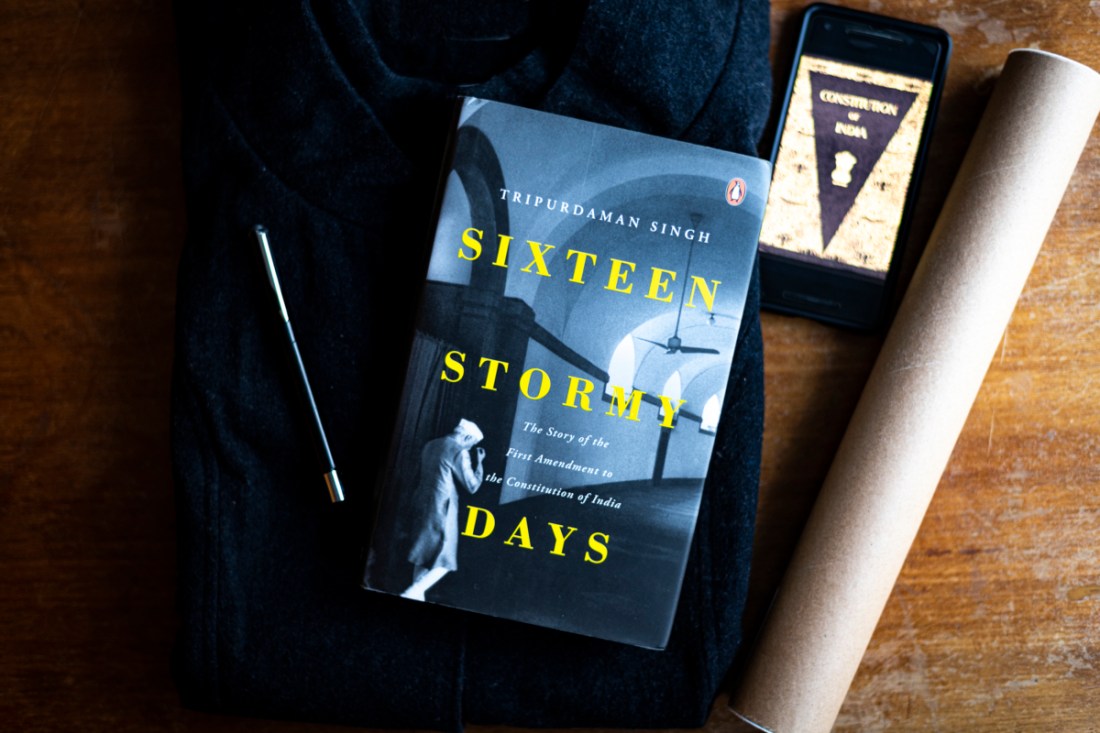

The year was 1950. A feeling of euphoria was palpable as, after three years of deliberation, the Constitution of a newly independent India had come into effect. The Nehru-led Congress was ready to hit the ground running till their grand plans came to a screeching halt in the face of an expansively liberal Constitution that stood in the way of nearly every major socio-economic plan in the Congress party’s manifesto. With a judiciary vigorously upholding civil liberties and a press fiercely resisting his attempt to control public discourse, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru created the constitutional architecture for repression and coercion in the form of the First Amendment to the Constitution.

‘Four months after the Constitution’s inauguration, it was becoming increasingly clear that the champions of personal freedom had feet of clay, that beneath the surface of an ostensibly democratic leadership lurked deeply authoritarian instincts.’ writes Tripurdaman Singh as he revisits the Sixteen Stormy Days in 1951 when fundamental rights—the heart and soul of the Constitution- become lacunae in the same Constitution.

Read on to find out how fundamental rights caused grave difficulties for the government in power-

The right to fight indefinite detention

On 6 February 1950, 28 detainees filed a petition before the Bombay High Court challenging the validity of the Bombay Public Safety Measures Act on the basis of the new Constitution which, under Article 22, made indefinite and open-ended preventive detention, without an advisory board to approve detentions beyond a period of three months, unconstitutional. The unprepared government took the first hit.

‘The detainees were no longer subjects seeking the government’s leniency and clemency; they were free, rights-bearing citizens, newly empowered by the Constitution written in their name, with the ability to knock on the doors of the highest court of the land to demand the liberties guaranteed to them.’

The furore over right to free speech

Barely three days after the twenty-eight communist detainees were freed by Bombay High Court another battle for Constitutional rights erupted in the Madras province when over 200 communist prisoners, demanding the status of political detainees rather than common criminals, went on strike. The violence that followed accelerated the downward spiral of the government and led to more strikes by other prisoners.

‘The enraged policemen retaliated by locking the 200-odd offenders in a hall with no means of escape and opening fire on them, killing twenty-two people in cold blood and injuring 107 others in a gruesome demonstration of the new republic’s lack of respect for the life and liberty of its citizens.’

The blurred promise of land reform

Land reform had been a major part Congress agenda and Zamindari abolition and land redistribution promised to herald a new phase of equality for a new India. However, even before the constitution came into effect a legal battle began to erode the promise made by Congress. Suits filed by pre-eminent zamindars led the courts to examine the constitutional validity of the entire Management of Estates and Tenures Act.

‘Observing that the drastic and far-reaching restrictions placed on the power of the proprietors to deal with their property with no corresponding compensation left them practically without any rights over their own property, the court held the law to be void ab initio—both before and after the creation of the Constitution.

The decision came as a bombshell, leaving the Bihar government and its Congress leaders shocked and rattled. The judgment reiterated the judiciary’s commitment to fundamental rights…’

The first legal challenge to the idea of reservation

Petitions filed against the discriminatory practice of reservation led courts to examine the issue of admissions being strictly regulated according to set communal proportions, instead of merit, which infringed upon fundamental rights. The violation of both Article 15 (1) of the Constitution of India, which protects citizens from discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth and Article 29 (2) formed the basis of the case. Noted lawyer Alladi Krishnaswamy Aiyyar laid bare the glaring issues in the ‘Communal Government Order’ in court-

‘Aiyyar argued that the right granted by Article 29 (2) of the Constitution, which in unequivocal terms prevented any discrimination in the matter of admissions to state or state-aided institutions, was an individual right personally granted to each citizen. It could not be sidestepped by granting restricted community-based opportunities, it was not a right granted to people as members of a particular caste or religion.’

The essential foundations of the Constitution, which Sardar Patel called its ‘idealistic exuberance’, had now become a real, multifold problem for Nehru who, irked by constitutional restraints obstructing his political goals, eventually wrote to his chief ministers-

‘Recent judgments of some High Courts have made us think about our Constitution. Is it adequate in its present form to meet the situation we have to face? We must accept fully the judgments of our superior courts, but if they find that there is a lacuna in the Constitution, then we have to remedy that.’

Thus began the story of the First Amendment to the Constitution.